Abstract

Objectives: Considering the aspiration embedded in the Sustainable Development Goals to Leave No One Behind by 2030, civil registration and vital statistics systems have an essential role in providing reliable, up-to-date information to monitor the progress. Thus, the aim of this systematic review is to compile empirical evidence on the benefits of a functioning civil registration and vital statistics system.

Methods: Selected databases were systematically searched until 2019. Key experts were also contacted for relevant literature. The review process was managed with the software EPPI-Reviewer and followed standard methods for systematic reviews.

Results: A total of 18 studies were included. The findings revealed that having birth, death, and/or marriage registration, and vital statistics were associated with access to rights and protection, positive impact on economic and health outcomes, and increased access to education.

Conclusion: The present review supports the idea that systemic approaches strengthen civil registration and vital statistics systems due to the cumulative effects of vital events’ registration. Ensuring appropriate systems for civil registration will have an impact not only on the individuals but also on the generations to come.

Introduction

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development represents a global effort to create a more equitable and sustainable world and it is comprised of seventeen goals referred to as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [1]. They set out the vital importance of providing legal identity for all, including birth registration by 2030 [2]. Aside from the fact that civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS) systems are a target in themselves, they play a key role in supporting and monitoring the progress towards many of the other SDGs targets [3]. Considering the commitment to meet the global aspiration to leave no one behind (LNOB) [4], a strong CRVS system is the most reliable source of up-to-date and continuous information.

Some of the benefits of a robust CRVS system are well documented [4], although knowledge gaps remain in this area. Unlike other data sources, a functioning CRVS system generates precise and up-to-date demographic and health indicators, providing a continuous stream of vital statistics for local administrative areas. CRVS data can be used by decisions-makers in any sector to detect areas of population change and reallocate resources as needed [5]. Within the context of COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of having a system which can reliably and continuously track fertility rates, mortality rates, and cause-of-death distribution to support public health decisions has been highlighted [6, 7]. Countries with well-functioning CRVS systems are able to produce timely and locally relevant mortality data that permit decision-makers to track mortality, for example due to HIV/AIDS or SARS-CoV-2 [8]. CRVS systems are being positioned as one of the essential services in the response to this health challenge, not only because they can provide information on the number and cause-of-death by age, sex and location, but because they can be also used to provide legal identification when needed to access health services [9].

In addition, CRVS systems also collect information on marriages, divorces, and adoptions [5]. Data on those vital events completes the demographic profile of countries and form the statistical foundation to understand citizens’ needs and design effective targeted policies [2, 10].

Research Gap

Despite the increased interest in strengthening CRVS systems, progress has been slow in most regions, and especially so in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [11]. Although the body of evidence around CRVS systems is considerable and continues to grow, it focuses mostly on how to strengthen the CRVS systems. Most research efforts have primarily looked at intermediate outcomes such as increases in birth registration, barriers to registration, and others.

However, to our knowledge, the effects of having a functioning system on individuals, in particular women, girls, and communities, as well as the mechanisms that underpin their impact, have not been identified and assessed in most settings.

To compile empirical evidence on the benefits of a functioning CRVS system, we have searched and reviewed all peer-reviewed and grey literature assessing the effects of the products of a functioning CRVS system (e.g., birth, death, marriage certificate or vital statistics) on individuals, communities or societies.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted following standard methodology described elsewhere [12], using a predefined protocol (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews identification number CRD42021226169), and following the PRISMA criteria for reporting of systematic reviews [13] (Supplementary File S2).

We reviewed peer-reviewed literature and grey literature as far as they met the inclusion criteria.

Search Strategy

General and grey literature databases were systematically searched for articles which examine the benefits from CRVS systems. No geographical location or date limitation was applied. CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PubMed, Econlit, Scopus, ELDIS, WHO, WHO IMSEAR and IndMED literature databases were systematically searched until June 2019 (Supplementary File S3). A manual search was performed within web-based databases and repositories of relevant institutions. Also, we approached key experts in the field and did a snowball search on the references of key publications was performed.

Eligibility Criteria

Eligibility criteria were based on key study features: population, intervention, comparator, outcome, and design, as recommended by the PRISMA group [

14]. Studies were included if:

(1) Population: Included any type of population;

(2) Intervention: Studies analysing the effect of the output of CRVS systems (e.g., benefits of registering a death). We excluded studies assessing the effect of interventions aimed at increasing the performance of CRVS systems (e.g., effect of interventions increasing registration completeness);

(3) Comparator: Studies with any comparator which could include the lack of new systems;

(4) Outcomes: Studies reporting quantitative and qualitative outcomes representing the benefit of CRVS system individuals (e.g. improved health outcomes); or societies including governments (e.g., improved governance, reduced fraud);

(5) Design: All types of study design in where methodology was described were included; and

(6) Written in English, Spanish, Portuguese or French.

The integration of quantitative and qualitative evidence is achieved at the level of the design. We applied a data-based convergent synthesis design, addressing one review question [15, 16]. The search strategy was designed by an independent information specialist, in consultations with the review team.

Selection of Studies

All types of study design examining the benefits from CRVS systems were included. The articles were identified based on the search strategy. The review process was managed with the online software EPPI-Reviewer engine®, utilising machine learning to support the screening process [17]. Duplicate references were removed. Two reviewers screened the selected records according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria following the Cochrane Handbook [12]. Any disagreement was resolved by consensus. Articles that met all inclusion criteria were included for quality assessment, using Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [18], and data extraction. Methodological quality was not used to exclude studies. The included studies were scanned to identify additional literature.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two reviewers completed the data extraction using a standardized template, including general information on the studies, setting, design, and quantitative and qualitative results. Data were categorised according to the type of effect described. The categorization of the effects was based on the themes emerging from the data extracted from the studies.

Quotes referring to benefits of CRVS systems were extracted from qualitative studies. Data extracted from quantitative studies included frequency and effect measures of CRVS systems’ products on specific outcomes, if available.

A gender and equity lens was applied when extracting the data. We assessed whether social characteristics, such as gender/sex, age, ethnicity, among others, were incorporated in the studies to understand how they played a role in contributing to inequities in the access to the benefits of a CRVS system.

Furthermore, we applied a narrative approach to synthesize the findings of the qualitative and quantitative evidence [15]. First, a preliminary synthesis of results was conducted, in form of a thematic analysis. During the process, the studies which focussed on the same outcomes were clustered. Relationships between the results on the different studies were analysed and the final cluster results were refined.

Results

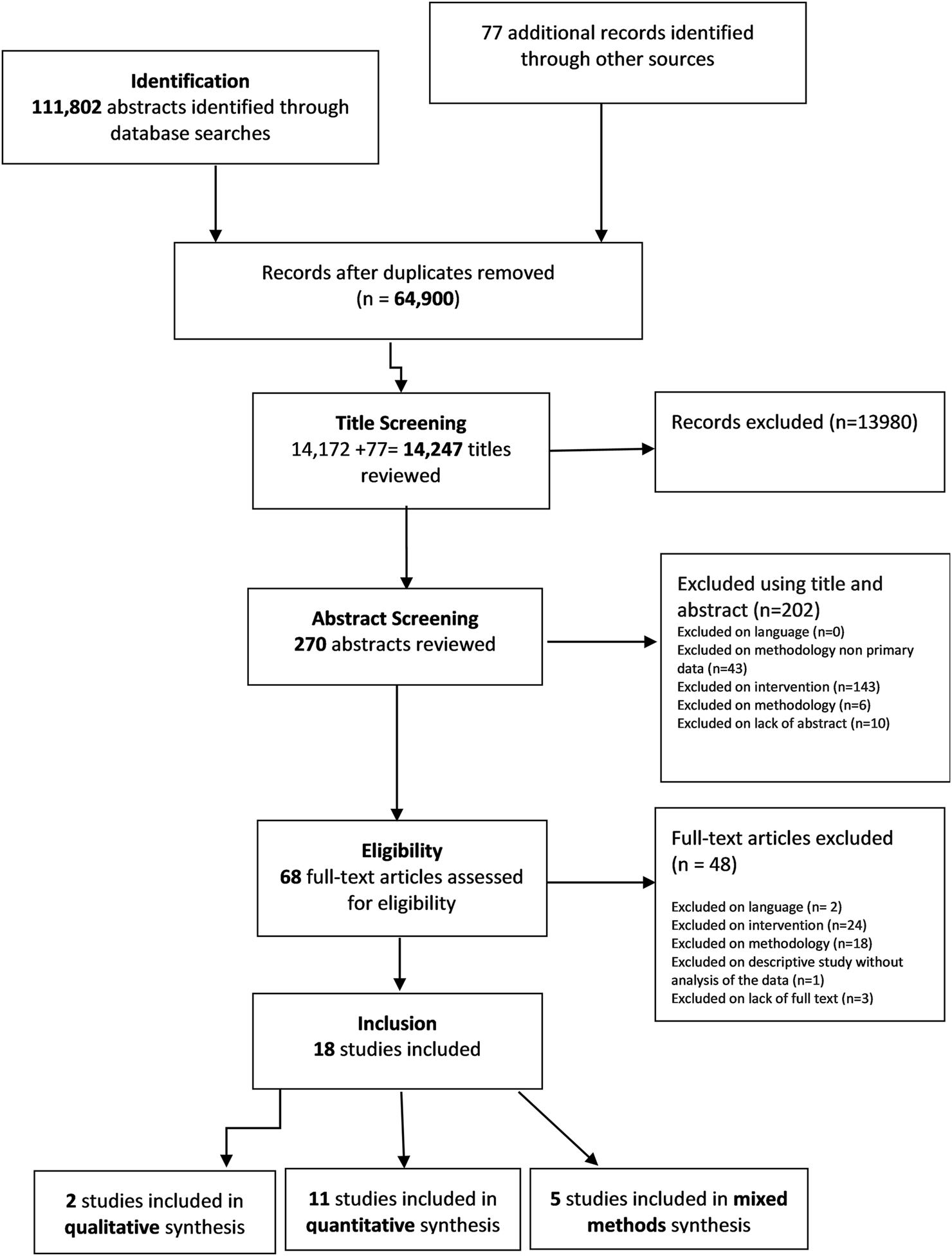

The screening and selection process is shown in Figure 1. We identified 111,803 records to review. Additional 77 additional studies were retrieved as a result of the inputs from key experts. A total of 18 studies met the eligibility criteria and were included for quality appraisal and data extraction. These included: two qualitative studies, 11 quantitative studies and five mixed methods studies conducted across four continents (Asia, America, Africa and Europe). The main characteristics of the studies can be seen in Table 1. Quantitative results are shown in Table 2.

FIGURE 1

Flow diagram of article selection. Addressing the evidence gap in the economic and social benefits of Civil Registration and Vital Statistics Systems: A Systematic Review, 2021. Adapted from PRISMA (Systematic review, Asia, America, Africa and Europe, 1910–2019).

TABLE 1

| References | Location | Year of data collection | Study type | Study population | CRVS output | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth Registration and Children’s Rights: A Complex Story | [19] | India, Kenya, Sierra Leone, Vietnam | 2005–2012 | Mixed methods | Children in rural and urban areas | Birth certificate and/or registration |

| Birth Registration and Protection for Children of Transnational Labor Migrants in Indonesia | [22] | Indonesia | 2014 | Qualitative | 22 families, and 54 adults, children aged 9–14 years in rural areas | Birth certificate and/or registration |

| Identifying the Rich: Civil Registration and State- Building in Tanzania | [25] | Tanzania | 2008–2015 | Quantitative | 4,000 households | Birth certificate and/or registration |

| Does birth under-registration reduce childhood immunization? Evidence from the Dominican Republic | [31] | Dominican Republic | 2007 | Quantitative | Children under 59 months of age | Birth certificate and/or registration |

| Underlying dynamics of child birth registration in Zimbabwe | [24] | Zimbabwe | 2014 | Mixed methods | Children—parents/guardian in 105 households in Bindura district | Birth certificate and/or registration |

| Birth registration and child undernutrition in sub-Saharan Africa | [30] | Thirty-seven sub-Saharan African countries | 2014 | Quantitative | Children under 5 years of age | Birth certificate and/or registration |

| Birth Registration and the Impact on Educational Attainment | [28] | Dominican Republic | 2007 | Quantitative | Children under 5 years of age | Birth certificate and/or registration |

| Papers, please! The effect of birth registration on child labor and education in early 20th century United States | [21] | United States | 1910–1930 | Quantitative | Children from 12 to 15 years old | Birth certificate and/or registration |

| Protection through Proof of Age. Birth Registration and Child Labor in Early 20th Century United States | [20] | United States | 1910–1930 | Quantitative | Children from 12 to 15 years old | Birth certificate and/or registration |

| Who Says I Do: The Changing Context of Marriage and Health and Quality of Life for LGBT Older Adults | [32] | United States | 2014 | Quantitative | LGBT Older Adults | Marriage certificate and/or registration |

| Associations between birth registration and early child growth and development: evidence from 31 low- and middle-income countries | [29] | 31 LMICs | 2010–2014 | Quantitative | Children aged 36–59 months | Birth certificate and/or registration |

| Back to what counts: Birth and death in Indonesia. Jakarta, Indonesia | [27] | Indonesia | 2015–2016 | Mixed methods | 5,552 individuals | Birth certificate and/or registration |

| 1,222 adults (95.7% female and 4.3% male) and 2,361 children (50.4% female and 49.6% male) | Death certificate and/or registration | |||||

| Marriage certificate and/or registration | ||||||

| Data for the Sustainable Development Goals: Metrics for Evaluating Civil Registration and Vital Statistics Systems Data Relevance and Production Capacity, Illustrations with Nigeria | [35] | Nigeria | 2003, 2008, 2013 | Qualitative | CRVS data | Vital statistics |

| Integrated human rights and poverty eradication strategy: the case of civil registration rights in Zimbabwe | [26] | Zimbabwe | 2005–2006 | Mixed methods | Individuals who were 13 years and older without any other restriction in their socio-demographic factors | Birth certificate and/or registration |

| Are well functioning civil registration and vital statistics systems associated with better health outcomes? | [10] | 144 countries | 2010 | Quantitative | CRVS performance data from 144 countries | Vital statistics |

| Difference-in-Differences Analysis of the Association Between State Same-Sex Marriage Policies and Adolescent Suicide Attempts | [33] | United States | 1999–2015 | Quantitative | Adolescents who participated in the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System in 47 states | Marriage certificate and/or registration |

| Impact of Civil Marriage Recognition for Long-Term Same-Sex Couples | [34] | United States | 2013 | Quantitative | Adults who identify as members of female, male same-sex couples | Marriage certificate and/or registration |

| The work of inscription: antenatal care, birth documents, and Shan migrant women in Chiang Mai | [23] | Thailand | 2010–2012 | Mixed methods | Shan migrant women from Myanmar in Chiang Mai | Birth certificate and/or registration |

Characteristics of the 18 studies included in the systematic review. Addressing the evidence gap in the economic and social benefits of Civil Registration and Vital Statistics Systems: A Systematic Review, 2021 (Systematic review, Asia, America, Africa and Europe, 1910–2019).

TABLE 2

| Effect | Indicator (references) | Exposure | Outcome | Result control group | Measure of effect | Results as reported by authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access to civil and social rights and services | ||||||

| Child Labour Elimination | Likelihood that child reports an occupation for individuals aged 12–15 [21] | Being born in a state with a child labour law but without a birth registration law | Child report an occupation | β = -0.034 | When born before registration law, children below the minimum age were 3.4% points less likely to work than work eligible children | |

| SE (0.008) | ||||||

| p < 0.01 | ||||||

| Likelihood that child reports an occupation for male individuals aged 12–15 [21] | Being born in a state with a child labour law and a birth registration law | Child report an occupation | β = 0.09 | Male individuals below the minimum aged, were 9% points less likely to work than the work-eligible than the work-eligible, when born with a birth registration law in place | ||

| SE (0.003) | ||||||

| p < 0.01 | ||||||

| Likelihood that child reports an occupation for black individuals aged 12–15 [21] | Being born in a state with a child labour law and a birth registration law | Child report an occupation | β = 0.078 | Black individuals below the minimum age were 7.8% points less likely to work than the work-eligible than the work-eligible, when born with a birth registration law in place | ||

| SE (0.003) | ||||||

| p < 0.01 | ||||||

| Likelihood that child reports an occupation in an urban area for individuals aged 12–15 [20] | Being born in a state without a birth registration law in an urban area | Child report an occupation | β = -0.028 | In urban areas, under-aged children born before the registration laws were 2.8% points less likely to work | ||

| SE (0.008) | ||||||

| p < 0.01 | ||||||

| Likelihood that child reports an occupation in a rural area for individuals aged 12–15 [20] | Being born in a state without a birth registration law in a rural area | Child report an occupation | β = −0.016 | In rural areas, under-aged children born before the registration laws were 1.6% points less likely to work | ||

| SE (0.007) | ||||||

| p < 0.05 | ||||||

| Likelihood that child reports an occupation in an agricultural county for individuals aged 12–15 [20] | Being born in an agricultural county with a birth registration law | Child report an occupation | β = −0.018 | In agricultural counties, children below the minimum age limit were 3.6 percentage points less likely to work if they were born with birth registration laws | ||

| SE (0.010) | ||||||

| Likelihood that child reports an occupation in a non-agricultural county for individuals aged 12–15 [20] | Being born in an agricultural county with a birth registration law | Child report an occupation | β = −0.028 | In non-agricultural counties, children below the minimum age limit were 5.9 percentage points less likely to work if they were born with birth registration laws | ||

| SE (0.007) | ||||||

| p < 0.01 | ||||||

| Access to protection services | Relationship correlating the access to Basic Education Assistance Module (BEAM) to birth certificate in Zimbabwe [24] | Having a birth certificate | Access to BEAM | p = 0.03 | The expansion of BEAM and other conditional cash transfers will likely reinforce parents’ and guardians’ perception of direct material benefits of child birth registration. In fact, the study found a significant relationship (p = 0.03) between access to beam and possession of birth certificates | |

| Positive impact on economic outcomes for individuals and governments | ||||||

| Increased the amount of tax payers | Likelihood that registered citizens paid council tax in Tanzania [25] | Having a birth registration | Tax outcomes | β = 0.229 | In one of the reform districts, registered citizens are 22.9 percentage points more likely to pay council taxes | |

| SE (0.099) | ||||||

| p < 0.05 | ||||||

| Increased the access to formal economic sector | Probability of having a bank account in Tanzania [25] | Having a birth registration | Finance outcomes | β = 0.477 | Birth registration is associated with a 47.7% point increase in the probability of someone in the respondent’s household possessing a bank account | |

| SE (0.244) | ||||||

| p < 0.05 | ||||||

| Human capital for economic development: Increased access to education and educational attainment | ||||||

| Increased access to education | Probability of being enrolled in formal education in India [19] | Having a birth certificate | Attending formal education | β = 0.6368 | A sponsored child with birth registration is 37% more likely to be attending formal education in India | |

| SE (0.156) | ||||||

| OR = 1.890 | ||||||

| p < 0.05 | ||||||

| Probability of being enrolled in formal education in Kenya [19] | Having a birth certificate | Attending formal education | Data not included | A sponsored child with birth registration is 50% more likely to be attending formal education in Kenya | ||

| Probability of being enrolled in formal education in Sierra Leone [19] | Having a birth certificate | Attending formal education | Data not included | A sponsored child with birth registration is 60% more likely to be attending formal education in Sierra Leone | ||

| Likelihood that child attends school for individuals aged 12–15 [21] | Being born in a state with a child labour law but without a birth registration law | Child school attendance | β = 0.036 | Under-aged children born before the registration law were 3.6 percentage points more likely to attend school than the work-eligible | ||

| SE (0.008) | ||||||

| p < 0.01 | ||||||

| Likelihood that child attends school for individuals aged 12–15 [21] | Being born in a state with a child labour law but with a birth registration law | Child school attendance | Data not included | Those born in a state with a birth registration law were 6.5 percentage points more likely to attend school than the work-eligible | ||

| Likelihood that school-age children were enrolled in Indonesia [27] | Having a birth certificate | Enrolled in school | AOR = 2.0, 95% CI = 1.6–2.5 | School-age children that were enrolled at the time of the study were twice as likely to have a birth certificate as those who were not enrolled in school | ||

| Increased educational attainment | Likelihood that children aged 11 to 18 pass the first cycle primary school in Dominic Republic [28] | Lack of birth certificate | Passing the first cycle primary school | OLS | An unregistered child would have between 20 and 40-% points lower probability of passing the first cycle of primary school | |

| β = −0.227 | ||||||

| SE = 0.084 | ||||||

| p < 0.01 | ||||||

| PROBIT | ||||||

| β = −0.393 | ||||||

| SE (0.217) | ||||||

| p < 0.1 | ||||||

| Years of education in 1960 (birth cohorts: 1896–1925), OLS [21] | Being born in a state with birth registration laws | Education | β = 0.083 | For individuals born in the United States between 1896 and 1925, the average educational attainment increased from 8.7 to 11 years | ||

| SE (0.21) | ||||||

| p < 0.01 | ||||||

| β = 0.103 | The coverage of the registration law increased from 25 to 100% for the same cohorts. Thus, a 0.09 years increase in attainment due to the birth registration laws would account for 3% of the total increase | |||||

| SE (0.31) | ||||||

| p < 0.01 | ||||||

| Probability of English literacy as an education outcome in Tanzania [25] | Having a birth certificate | Education | β = 0.411 | This effect on the population of compliers, birth registration is associated with a 41-percentage point increase in the probability of English literacy | ||

| SE = 0.185 | ||||||

| p < 0.05 | ||||||

| Likelihood that adults attended elementary or middle school in Indonesia [27] | Having a birth certificate | Attended elementary or middle school in Indonesia | AOR = 2.1, 95% CI = 1.1–3.8 | Adults that had attended elementary or middle school were twice as likely to have a birth certificate as those who had not attended school | ||

| Likelihood that adults attended high school or higher in Indonesia [27] | Having a birth certificate | Attended high school or higher | AOR = 3.7, 95% CI = 1.9–7.2 | Adults that had attended high school or higher were almost four times as like to have a birth certificate than those who had not attended school | ||

| General | Likelihood that Healthy Life Expectancy (HALE), in 144 countries [10] | Associated to vital statistics performance index (VSPI) | HALE | β = 1.044 | HALE was estimated to increase by 0.044% with each unit increase in VSPI on a 100-point scale | |

| 95% CI [1.020–1.068] | The regression indicates that if worldwide CRVS performance was high (0.9) rather than at its worldwide average based on the 144 countries or territories with available data (0.591), average HALE would increase by nearly 1 year (63.1 years vs. 62.3 years) | |||||

| p < 0.0005 | ||||||

| Likelihood that Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) in 144 countries [10] | Associated to vital statistics performance index (VSPI) | MMR | β = 0.721 | Countries with high VSPI values have low MMR. | ||

| 95% CI | ||||||

| 0.508–1.023 | ||||||

| p = 0.067 | ||||||

| Likelihood that child mortality risk (5q0) values, in 144 countries [10] | Associated to vital statistics performance index (VSPI) | 5q0 | β = 0.418 0.367–0.470 | Countries with high VSPI values have low 5q0 | ||

| p = 0.002 | ||||||

| Improved nutrition | Values of children’s height-for-age Z-score (HAZ) in 40 cases out of 140 comparisons [30] | Registered vs. not registered children | HAZ | p < 0·1 | Effects of selection bias due to birth registration on undernutrition prevalence | |

| 28.6% | Registered children generally presented a better nutritional status than unregistered ones, with significantly higher HAZ mean values in 40 cases out of 140 comparisons: 28.6% | |||||

| Values of children’s Weight for age Z-score (WAZ) in 51 cases of 140 comparisons [30] | Registered vs. not registered children | WAZ | p < 0·1 | Effects of selection bias due to birth registration on undernutrition prevalence | ||

| 36.4% | Registered children generally presented a better nutritional status than unregistered ones, with significantly higher WAZ mean values in 51 cases out of 140 comparisons: 36.4% | |||||

| Values of children’s Weight-for-height Z-score (WHZ) <–2) in 38 cases of 140 comparisons [30] | Registered vs. not registered children | WHZ | p < 0·1 | Effects of selection bias due to birth registration on undernutrition prevalence | ||

| 27.1% | Registered children generally presented a better nutritional status than unregistered ones, with significantly higher WHZ mean values in 38 cases out of 140 comparisons: 27.1% | |||||

| Likelihood that children are stunting in Uttar Pradesh, India [19] | Having a birth registration | Nutrition outcomes | β = -0.073 | In Uttar Pradesh a child with birth registration is approximately 0.7 times less likely to be stunted | ||

| SE (0.019) | ||||||

| OR [0.670] | ||||||

| p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Likelihood that children are under-weight in Uttar Pradesh, India [19] | Having a birth registration | Nutrition outcomes | β = -0.0423 | In Uttar Pradesh a child with birth registration is approximately 0.8 times less likely to be under-weight | ||

| SE (0.018) | ||||||

| OR [0.781] | ||||||

| p < 0.05 | ||||||

| Likelihood that children are stunting in Kenya [19] | Having a birth registration | Nutrition outcome | β = -0.0548 | In Kenya a child with birth registration is approximately 0.8 times less likely to be stunted | ||

| SE (0.023) | ||||||

| OR [0.767] | ||||||

| p < 0.005 | ||||||

| Likelihood that children are under-weight in Kenya [19] | Having a birth registration | Nutrition outcome | β = -0.00712 | In Kenya a child with birth registration is approximately 0.7 times less likely to be under-weight | ||

| SE (0.021) | ||||||

| OR [0.658] | ||||||

| p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Likelihood of children’s height-for-age z-scores (HAZ) aged 36–59 months in 31 LMICs [29] | Lack of birth certificate | Nutrition outcome | β = −0.18 | Not having a birth certificate was negatively associated with children’s HAZ | ||

| 95% CI: −0.23, −0.14 | ||||||

| p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Likelihood of children’s weight-for-age z-scores (WAZ) aged 36–59 months in 31 LMICs [29] | Lack of birth certificate | Nutrition outcome | β = − 0.10 | Not having a birth certificate was negatively associated with children’s WAZ | ||

| 95% CI: −0.13, −0.07 | ||||||

| p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Likelihood of children’s ECDI z-score aged 36–59 months in 31 LMICs [29] | Lack of birth certificate | Nutrition outcome | β = −0.10 | Not having a birth certificate was negatively associated with children’s ECDI z-scores | ||

| 95% CI: −0.13, −0.07 | ||||||

| p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Better vaccination outcomes | Effect on number of vaccines for children aged 0–59 months in Dominic Republic [31] | Lack of birth certificate | Immunisation | β = -0.755 | This estimate suggests that lacking a birth certificate is associated with a reduction of 0.7 vaccines | |

| SE (0.156) | ||||||

| p < 0.01 | ||||||

| Effect on vaccination outcomes in Uttar Pradesh, India [19] | Having a birth registration | Immunisation | BCG | Children with birth registration in Maharashtra, India are between 1.2 and 3.8 times more likely to have been vaccinated than children without birth registration, depending on the type of vaccine (e.g., BCG, POL0, DPT1, DPT2, DPT3, Measles, POL1) | ||

| SE (0.031) | ||||||

| OR [2.127] | ||||||

| POL 0 | ||||||

| SE (0.032) | ||||||

| OR [1.898] | ||||||

| DPT1 | ||||||

| SE (0.031) | ||||||

| OR [2.092] | ||||||

| DPT2 | ||||||

| SE (0.033) | ||||||

| OR [2.012] | ||||||

| DPT3 | ||||||

| SE (0.033) | ||||||

| OR [1.815] | ||||||

| Measles | ||||||

| SE (0.033) | ||||||

| OR [2.006] | ||||||

| p < 0.01 | ||||||

| — | ||||||

| POL 1 | ||||||

| SE (0.016) [1.805] | ||||||

| p < 0.1 | ||||||

| Effect on vaccination outcomes in Kenya [19] | Having a birth registration | Immunisation | BCG | Children with birth registration in Kenya are between 1.3 and 2.2 times more likely to have been vaccinated than children without birth registration, depending on the type of vaccine (e.g. BCG, POL0, DPT1, DPT2, DPT3, Measles, POL1) | ||

| SE (0.014) | ||||||

| OR [2.235] | ||||||

| POL 0 (0.019) [1.807] | ||||||

| DPT1 (0.015) [1.887] | ||||||

| POL 1 (0.015) [1.901] | ||||||

| DPT2 (0.017) [1.866] | ||||||

| POL 2 (0.017) [1.700] | ||||||

| DPT3 (0.019) [1.469] | ||||||

| POL 3 (0.020) [1.364] | ||||||

| Measles (0.020) [1.484] | ||||||

| p < 0.01 | ||||||

| Effect on vaccination outcomes in Sierra Leone [19] | Having a birth registration | Immunisation | BCG | Children with birth registration in Sierra Leone are between 1.6 and 2.1 times more likely to have been vaccinated than children without birth registration, depending on the type of vaccine (e.g. BCG, POL0, DPT1, DPT2, DPT3, Measles, POL1) | ||

| SE (0.016) | ||||||

| OR [2.126] | ||||||

| POL0 (0.020) [1.658] | ||||||

| p < 0.05 | ||||||

| — | ||||||

| DPT1 (0.018) [1.845] | ||||||

| POL 1 (0.018) [1.948] | ||||||

| DPT2 (0.019) [1.767] | ||||||

| POL 2 (0.019) [1.797] | ||||||

| DPT3 (0.019) [1.711] | ||||||

| Measles (0.019) [1.589] | ||||||

| p < 0.01 | ||||||

| Improved mental health and quality of life | Changes in high school student (ages 15–19) suicide attempts in US. Net Change in Suicide Attempts, Percentage Points [33] | After implementation of Same-Sex Marriage Policies | Suicide attempts- (Students identifying as sexual minorities) –4.0 | (All students) −0.6 | 95% CI | The reduction in suicide attempts, represents a 7% relative reduction in the proportion of high school students attempting suicide owing to same-sex marriage implementation |

| –6.9 to –1.2 | ||||||

| p < 0.01 | ||||||

| — | ||||||

| 95% CI | These results are equivalent to a 14% relative decline in the proportion of adolescents who were sexual minorities reporting suicide attempts in the past year | |||||

| –1.2 to –0.01 | ||||||

| p < 0.05 | ||||||

| Positive LGBIS identity and social support outcomes by marital status and state recognition [34] | Having a marriage registration | LGB Identity centrality | 95% | The positive coefficients for marital status indicate that individuals who are in a civil marriage report significantly higher levels of LGB identity centrality | ||

| γ020 = 0.20 | CI = [0.04, 0.36] | |||||

| p < 0.05 | ||||||

| Positive LGBIS identity and social support outcomes by marital status and state recognition [34] | Having a marriage registration | Social support from partner γ020 = 0.17 | 95% | The positive coefficients for marital status indicate that individuals who are in a civil marriage perceive their partner as more supportive | ||

| CI = [0.04, 0.30] | ||||||

| p < 0.01 | ||||||

| Mean/(SE) or %—general health and quality of life (QOL) characteristics by relationship status and gender, between married and unmarried partnered men in 2017, United States [32] | Having a marriage registration | General Health married men | unmarried partnered men | p < 0.05 | Married men showed advantages over unmarried partnered men in general health -QOL | |

| 3.62/(0.10) | 3.29/(0.11) | |||||

| Mean/(SE) or %—physical health and quality of life (QOL) characteristics by relationship status and gender, between married and unmarried partnered men in 2017, United States [32] | Having a marriage registration | Physical Health married men | unmarried partnered men | p < 0.05 | Married men showed advantages over unmarried partnered men in physical health -QOL | |

| 77.05/(1.39) | 69.58/(2.45) | |||||

| Mean/(SE) or %—environmental health and quality of life (QOL) characteristics by relationship status and gender between married and unmarried partnered men in 2017, United States [32] | Having a marriage registration | Environmental Health married men | Unmarried partnered men | p < 0.05 | Married men showed advantages over unmarried partnered men in environmental health -QOL | |

| 82.51/(1.39) | 75.72/(1.45) | |||||

| Mean/(SE) or %—general health characteristics by relationship status and gender—quality of life (QOL) between married and single women in 2017, United States [32] | Having a marriage registration | General Health married women | Single women | p < 0.05 | Married women showed advantages over single women in general health -QOL | |

| 3.64/(0.10) | 2.88/(010) | |||||

| Mean/(SE) or %—psychological health -quality of life (QOL) characteristics by relationship status and gender between married and single women in 2017, United States [32] | Having a marriage registration | Psychological | Single women | p < 0.05 | Among women, those who were legally married had better general health, lower rates of disability, and better QOL across all domains compared with those who were single | |

| Health married women | 62.22 (2.05) | |||||

| 71.64 (1.42) | ||||||

| Mean/(SE) or %—social health and quality of life (QOL) characteristics by relationship status and gender between married and unmarried women in 2017, United States [32] | Having a marriage registration | Social | Unmarried women | p < 0.05 | Married women only had greater social QOL than those unmarried partnered | |

| Health married women | 63.39 (2.49) | |||||

| 72.85 (1.87) | ||||||

Quantitative results extracted from the 18 studies included in the systematic review. Addressing the evidence gap in the economic and social benefits of Civil Registration and Vital Statistics Systems: A Systematic Review, 2021 (Systematic review, Asia, America, Africa and Europe, 1910–2019).

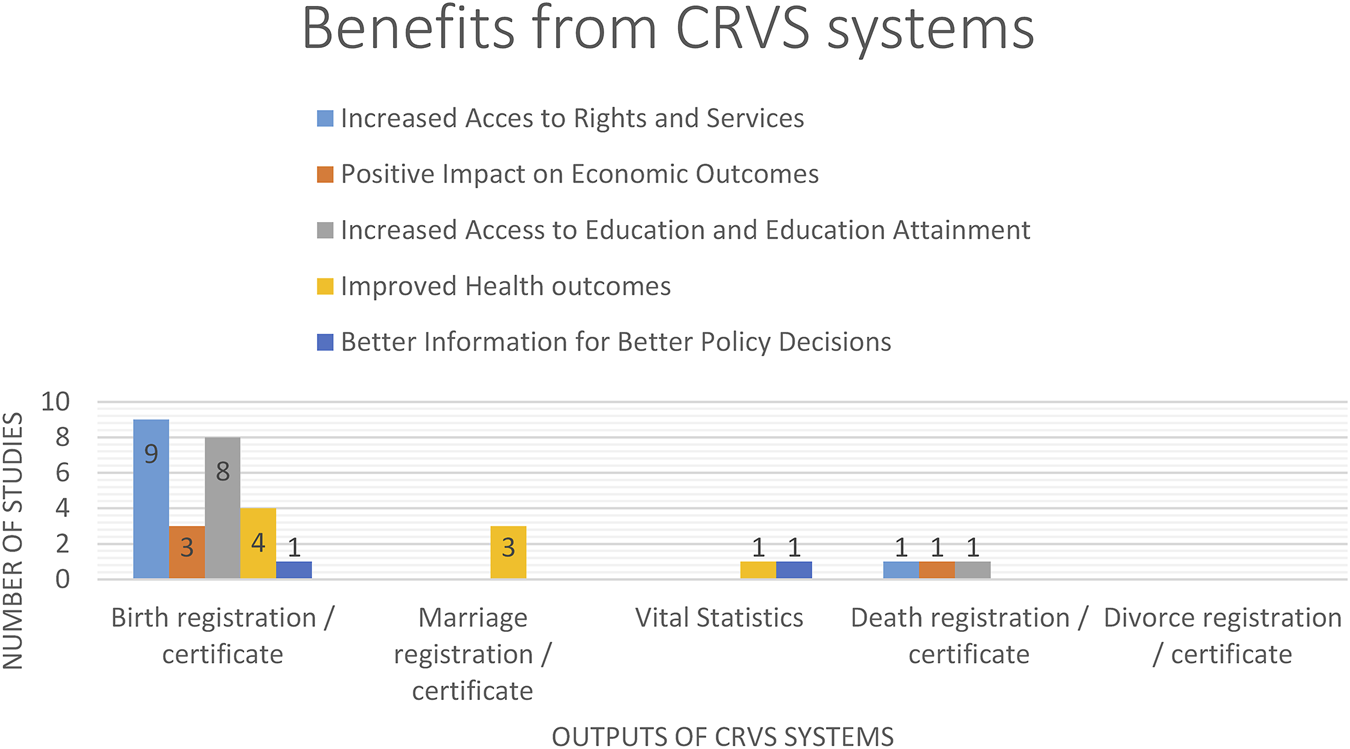

We report the results of the studies in six sections: 1) access to civil and social rights and services, 2) positive impact on economic outcomes for individuals and governments, 3) human capital for economic development: increased access to education and education attainment, 4) improved health outcomes, 5) better information for better policy decisions. The benefits from each vital event are shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2

Table Chart of the benefits of CRVS systems per vital event. Addressing the evidence gap in the economic and social benefits of Civil Registration and Vital Statistics Systems: A Systematic Review, 2021 (Systematic review, Asia, America, Africa and Europe, 1910–2019).

The two qualitative and 11 quantitative studies achieved a moderate methodological quality, while the mixed-methods studies were found to be of lower quality due to the quantitative components. The poorest scoring items on the MMAT were the questions related to the sampling strategy and the risk of nonresponse bias. All the studies had a clear study question and presented the results with clarity (Supplementary File S1).

Access to Civil and Social Rights and Services

The links of vital registration to other human and civil rights have been extensively investigated in the included studies. Ten out of eighteen studies focused on the effect of birth registration on child protection and access to services, specifically the prevention of child labour and access to legal identity documents.

Having proof of age is not only an essential element for governments to run protection programs but also to prevent child labour and child marriage through the enforcement of laws [19–21]. It has been also seen as a way to defend them in situations where their rights have been violated.

“If you don’t have a birth certificate, and you are abused, no one will know if you are a child or not, so they can’t do anything.” (a Plan program staff in urban Sierra Leone) [19].

A study suggested that child labour laws and schooling laws implemented between 1910 and 1930 in the United States reduced under-aged employment and raised the school attendance of school-aged children [21]. The effect was also seen across ethnicities [21], and geographical location [20]. Results were consistent with those reported in India, Kenya and Sierra Leone [19].

Another group of studies looked at the impact of vital registration on migrant populations. In Indonesia [22], Sierra Leone [19], and Thailand [23], authors concluded that birth registration is a pathway to access the education and obtain legal identity documents. As a consequence, it increases the likelihood for those individuals to access better economic opportunities. In Thailand, it was reported that having a birth certificate gives rights and citizenship to migrant children from Myanmar [23].

“When he reaches 15 years, he can apply for a Thai identification card, because we already have both his birth registration and have prepared all the documents required of him (…).” (Shan woman in her mid-30s) [23].

In Zimbabwe, the function of a birth certificate was underlined as documentary proof of family and kinship by each respondent in the study.

“(…) a vehicle for establishing blood ties to a father, family and kinship group whilst validating one’s nationality and citizenship.” [24].

Access to social protection programs, such as conditional cash transfer programs, food subsidies or education support is not possible without a birth certificate in many countries. In Zimbabwe, participants in a study reported that the birth certificate as a way to identify children and allow them to access cash transfers and school feeding schemes [24]. In Vietnam, being registered to one specific household was essential to have any social protection from the state, which could have a lifetime effect [19].

“(…). Birth certificates are very useful in so many cases in Vietnam: even when people become 80 years old they will need a birth certificate to get a pension” (parents in a FGD, Vietnam) [19].

In Tanzania, a study showed the positive effect of birth registration on gaining access to social security systems, formal employment, property rights and better house quality [25].

Positive Impact on Economic Outcomes for Individuals and Governments

Results of three studies highlighted the association between birth registration to increased access to formal labour employment, banking and probable improvement in the individual’s socioeconomic status. On the government side, having a functioning CRVS system was associated with increased tax revenue, improved administrative and governance processes and targeting social and economic subsidies and incentives.

In Tanzania, researchers concluded that citizens who were registered were 22.9% points more likely to pay council taxes. A positive relationship was shown between having a birth certificate and working in the formal private sector as a paid employee. The study also showed a 47.7% point increase in the probability of having a bank account [25]. The authors stressed the risks of using the argument of the increase in tax revenue as this could lead to target only richer segments of the population in CRVS strengthening efforts which would perpetuate structural inequities in the population [25].

In a multi-country study, it was claimed that having a birth certificate not only improved access to the formal sector but also to jobs that are better paid and stable within the Government or large companies [19].

“(…). For the Government jobs they want them. They want to know your age so that they can know when you are going to retire.” (family’s interview, in India) [19].

“If you are working for the Government, or if you have one of those office jobs.” (mother, in Sierra Leone) [19].

In Zimbabwe, authors explored the impact of having civil registration documents, particularly birth registration, on the poverty eradication strategy. It was found that citizens had to make eight to ten attempts to collect the documents and that most of the respondents were affected by the lack of parent’s certificates. Nevertheless, 81.4% of citizens stated that they would still go through the process again due to the attached importance [26].

The benefit of having a death certificate was explored in a study in Indonesia. Respondents highlighted the importance of this certificate in order to claim the spouse’s pension (10.6%), or grief compensation allowance or inheritances (9.6%), and closing out the bank accounts or health insurances (28.8%). The lack of knowledge of the benefits of having a death certificate (43.8%) was one of the major barriers appointed by the respondents [27].

Human Capital for Economic Development: Increased Access to Education and Educational Attainment

Nine studies suggested a positive relationship between the possession of a birth certificate and the ability of the child to access education [19, 21, 24, 25, 27]. Children with a birth certificate in India, Kenya and Sierra Leone, were 37%, 50% and 67% more likely to attend school respectively [19]. It was also reported that the lack of a birth certificate did not affect everyone equally. Not only girls reported more gender discrimination experiences, but also, those with privilege could influence the system to obtain a certificate and eliminate barriers.

“…birth certificates are a basic requirement. But if you have the money and influence you can solve anything. Money is given and the rules are easily broken.” (young person, India) [19].

Researchers further supported the idea that birth registration laws were associated with a higher likelihood of children attending school in the United States (6.5% points higher in children born after the registration law) [20, 21]. In Tanzania, having a birth certificate was associated with being more literate, starting school younger and completing more education years (41% points increase in the probability of English literacy) [25].

Further studies also investigated the association between having a birth certificate and the educational attainment of children. In the Dominican Republic, children without a birth certificate had a lower probability of passing the first schooling cycle [28]. In the United States the implementation of the birth registration law increased the average of educational attainment from 8.7 to 11 years and the coverage of the registration law from 25 to 100% for the same cohort [21] and in Zimbabwe respondents believed that the lack of birth registration had negatively affected their education [26].

The interdependency among vital events’ registration was captured in different population groups in Indonesia. Among migrant populations, the lack of a marriage certificate was considered a barrier in registering the birth of a newborn, which has negative consequences during child’s lifetime [22]. Those challenges are reinforced by the existing religious and cultural norms which prevent the most vulnerable groups, such as single mothers, unmarried couples of obtaining legitimate birth registration, those having a parent with a disability, or women working overseas [22].

“A government midwife in one of the villages (…) was ‘not brave enough’ to accept unmarried couples or single mothers as clients due to stigma at the village level against children born out of wedlock. Women who become pregnant out of wedlock in Indonesia or while working overseas cannot get official statements of birth, impeding their access to a legitimate birth certificate for their newborn.” [22].

In Indonesia, adults who attended high school and children in school were almost four-times and twice as likely, respectively, to attain a birth certificate. So, access to education was one of the main reasons families persuaded the certificates for their children [27].

“If they don’t have a [birth certificate], they won’t be able to enrol in school. That’s the point when the communities started to get birth certificates.” (official, Indonesia) [27].

In Zimbabwe and Indonesia, the lack of parental documents affects children’s birth registration [26, 27]. It was noticed that non-registration influences the decision to continue education due to the barriers caused by not having registration documents. It seems that there is a clear connection between the lack of birth registration and early marriage or early employment [26]. This interdependency between the vital events’ registrations affected parents who could not register their marriage due to the lack of their own birth certificates.

“(…) if getting married needs a birth certificate, for those who don’t have one [KUA] won’t take their application (…)” (participant FGD, Indonesia) [27].

From an operational perspective, the dependency among vital events registration means that focusing on just one area of a CRVS system will not yield the full potential of these systems to improve the lives and wellbeing of individuals, including the most neglected.

Improved Health Outcomes

Eight studies showed a positive association between birth and marriage registration and having vital statistics with nutrition, immunisation, better mental health and quality of life, having a direct effect for women, children and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex (LGBTQI) people.

In a modelling exercise, researchers found a positive relationship between the vital statistics performance index and the national estimates of healthy life expectancy, maternal mortality ratio, and child mortality risk (5q0) in 144 countries [10]. Some further studies have identified birth certificates as the gateway document to access health services or national health insurance programmes. In Vietnam, birth certification was compulsory to obtain a health insurance card [19].

Three studies showed the impact of birth registration on child nutrition and development outcomes. Researchers estimated that the lack of a birth certificate was associated with lower height-for-age z-scores (stunting), weight-for-age z-scores (underweight), and early child development index among children aged 36–59 months using data from 31 LMICs [29]. Similar results were reported in an analysis of multiple indicator cluster surveys from 37 Sub-Saharan countries [30]. In this same study, authors found a potential for selection bias in surveys favouring registered children (or children with a valid date of birth) that could lead to an underestimation of the undernutrition prevalence (up to 28% in some cases). Evidence from India and Kenya supports these findings where children with a birth certificate were less likely to be stunted and underweight [19].

Studies conducted in several countries consistently reported a positive correlation between being registered at birth and vaccination outcomes, in which respondents considered of great importance to know the precise age to provide age-appropriate care [19, 31]. In the Dominican Republic, authors reported that children between 0 and 59 months that did not have birth certificates were behind by nearly one vaccine (out of a total of 9) [31]. In Kenya and India, researchers showed that children had from 1.2 to 3.8 higher chances of being vaccinated, depending on the type of the vaccine, when possessing a birth certificate [19].

A number of studies evaluated the association between civil registration and mental health among LGBTQI people in the United States [32–34]. An analysis of the survey “Aging with Pride” showed that legally married same-sex couples, were advantaged over unmarried partners and singles, having a better general, physical and environmental health [32]. It was showed similar results and confirmed that civil marriage has a positive impact on the wellbeing of individuals in long-term same-sex couples across all the USA states [34]. The association between state same-sex marriage policies and adolescent suicide attempts was investigated in the United States [33]. The application of same-sex marriage policies was associated with a reduction of 0.6% points in suicide attempts among high school students, accounting for a 7% relative reduction in the proportion of high school students who attempted suicide. And the reduction of 4% points in suicide attempts among sexual minorities, equivalent to a 14% relative decline [33].

Better Information for Better Policy Decisions

Having accurate information about births, deaths and cause-of-death is essential for governments to inform policies. A recent study in Nigeria concluded in their analysis that the national CRVS systems could provide relevant data for up to 25% of the SDGs [35]. However, given the current performance of the system, the CRVS system could not be used to this end. In a multi-country study, Kenya, Sierra Leone, India and Vietnam, government officials stated that accurate data gathered by the civil registration offices is essential at central, district and local levels [19].

“We need to know the region the child comes from. This is important to ensure that resources are allocated correctly. We have some areas that are disadvantaged in the northeast regions. We have a programme that targets these regions—girls are provided for when they go to secondary school” (representative from MoE, Kenya) [19].

The lack of disaggregated data from vital statistics (e.g., sex, age and geographical location) remains critical component in many states. Research has highlighted that disaggregation is a priority for the government to allocate resources appropriately [19].

Discussion

CRVS systems are complex adaptive systems that perform hundreds of activities daily [36] and impact individuals and societies through multiple channels. Identifying the pathways by which countries can benefit from having a functioning CRVS system is an essential element to advocate for further support to strengthen them. Researchers captured some of these pathways in a model that accounted for some of the complexity in the relationship between CRVS performance and health outcomes. Even though the authors succeeded in generating a robust argument for the effect of CRVS on health, the model was silent about the evidence supporting some of the key assumptions made in the calculations [10]. With this review, we try to fill part of that gap with a systematic analysis of the literature published about the economic and social benefits of CRVS systems.

The evidence included in this review suggests that CRVS systems are enablers for citizens, particularly for women, girls and diverse people (such as people with different ethnicities, gender, sexual orientation, abilities and location), in accessing civil rights [19–24] or social protection programs [19, 24, 25, 27]. A consistent association with improved health [19, 29–34] and education outcomes [19, 21, 24, 25] was also found.

Historical evidence, such as the Shattuck Report on birth and death statistics set the groundwork for the creation of health and social policies in the United States [37]. Further studies demonstrated that vital events registration and certification might result in several society and individual benefits [38, 39]. Also, vital registration creates important data with significant policy utility [39–41]. England and Sweden country cases showed that when a CRVS system is adopted on a systematic basis, certainly led to better health and socioeconomic growth [39].

Further evidence has suggested that birth registration can provide timely information to health decision-makers about the numbers of infants eligible for early childhood vaccinations. Conversely, unregistered children who are brought to vaccination centers can benefit from later or delayed registration. This mutually beneficial relationship is common, especially in settings where vaccination rates and higher than birth registration rates [42–44]. CRVS systems also proved to have a positive impact on economic outcomes for governments since they can enhance the capacity to identify citizens which contribute to increasing tax revenue [45] as well as better administrative and governance procedures [19] and better targeting social and economic subsides and benefits [46].

One of the most striking findings that emerged from this review is that, despite the importance of CRVS systems as a government function [19], there remains a paucity of published evidence on the impact of CRVS systems at any level. We found a significant body of knowledge investigating either interventions to strengthen CRVS systems (e.g., how to increase birth registration) [47], or evaluating their performance [48], but little has been published on the effects of having a birth or death certificate on people’s wellbeing. There is a great potential of such interventions to generate quasi-experimental evidence on the (causal) impact of CRVS systems on the outcomes of interest. When looking at the products form the CRVS system that has been investigated, most of the studies focused on the registration/certification of births. There was limited evidence describing the direct or indirect benefits of having a death registration system in place. Attaining a death certificate was highlighted to be eligible to receive the death benefits, claim insurances or inheritances, as well as cancelling accounts [27]. The need for empirical evidence describing the benefits of death registration data from CRVS systems is essential to enhance the value and increase the government’s incentives to invest in innovation [49].

CRVS systems are especially beneficial for vulnerable groups and neglected communities, including migrant population [19, 23, 24, 27, 50]. The lack of civil registration as a consequence of the interplay between different social factors that excluded at-risk groups from accessing fundamental rights and services, putting them at a higher threat of exclusion [51]. Legal documents produced by CRVS systems such as birth and marriage certificates allow citizens to access other legal documents such as a passport, national ID or voting card [19, 24, 25]. Further literature suggested that women can use a marriage certificate to prove changes in residence or name after marriage when registering to vote [52], as well as governments prevent vote fraud. A birth certificate gives them also a documentary proof of identity and kinship as a way to establish the family ties and track the major events of the life of a child’s life [24, 27]. There is a wealth of documented experiences on the effects of births and marriage registration in preventing child marriage [50, 53, 54], however no empirical research was found. In humanitarian or emergency contexts, children are extremely vulnerable, and the registration of a newborn birth can support family tracing and the entitlement of rights [55].

One interesting finding from this review is that the benefits of the registration/certification of the different vital events are interdependent and have a cumulative impact across the life course of individuals [22, 24, 26]. This argument is consistent with previous evidence, arguing the importance of civil registration for minority groups populations across generations [56–59]. Recent evidence from the Syrian crisis showed how not having verification of marriage may be a bottleneck registering other vital events, which often sustains and amplifies statelessness among children [60, 61]. These findings reinforce the need for systemic approaches to strengthening CRVS systems. Rather than focusing on one vital event, governments need to assure that vital events throughout the entire life course of individuals are registered, certified and included in the vital statistics [62].

Strengthening CRVS systems has become a priority in the global agenda. A large number of countries declared CRVS as essential service worldwide during the COVID-19 pandemic [63–65]. The statistical operations worldwide, including the activities of CRVS systems, has been substantially impacted [63–65]. There is a need to integrate a strategic and systematic approach to support inclusive and sustainable development. However, political will and in-country long term investments are necessary to achieve the current goals. Building links across sectors will increase the stated benefits of CRVS systems, for both the government and its citizens. It will not only avoid fragmentation and increase efficiency, but also facilitate to verify the authentication of people and the occurrence of vital events to claim rights [47, 66]. CRVS systems has the potential to produce timely and relevant statistics [19], and when synchronised with other population data sources, can be mutually-reinforcing. The current crisis underlined the relevance of the digital transformation, while also creating new chances to expand and modernize national statistical agencies [67].

This systematic review is subject to some limitations. First, only studies written four languages were included. We cross-checked previously identified relevant studies to minimise the chances that relevant papers would have been excluded. Second, due to the reduced numbers of studies included, no quantitative sub-analysis was conducted. Selective reporting in both qualitative and quantitative studies could not be ruled out. Third, when matching the inclusion criteria, the methodological quality was moderate to weak, providing vague evidence to show a causal impact. Fourth, this systematic review found evidence of only two of the multiple vital events, such as birth and marriage registration. Including whether the missing interventions had effects on additional outcomes merits further research.

Conclusion

In conclusion, to our knowledge, this systematic review is the first assessment on the benefits of a functioning CRVS system.

Findings from our systematic review suggested that a strong and accessible CRVS system have a broad range of benefits for individual, communities and governments. Most studies focused on the benefits of registering or certifying vital events such as birth or marriage, as well as vital statistics. The benefits of the registration or certification of death events was appallingly neglected in the literature. This systematic review reinforces the idea of systemic approaches to strengthening CRVS systems due to the cumulative effect found in a number of studies.

There is a need to better document the impact of functioning CRVS systems with robust study designs and that represent different regions and populations. It is also essential to assess the effects of CRVS systems in different population groups using intersectional lens.

Future updates of this review ought to pursue the follow up of the studies stated here, as well as any upcoming investigations.

While this review has not found a large number of studies with a strong scientific methodology demonstrating effects associated with the registration of vital events, the implication for practise and research is that strengthening CRVS systems will increase the benefits for individuals and societies across the life course and across generations, providing governments with information essential for public decision-making.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets supporting the conclusion of this article are included within the article and its Supplementary Material.

Author contributions

CSF, DDS, and DCM: Study conception; RRB, CSF, and DCM: Design and develop the study protocol; RRB, CSF, and DCM: Data curation, analysis and interpretation of results; RRB: Visualization; RRB and DCM: Writing—original draft; RRB, CSF, ID, DDS, and DCM: Writing—review and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that this study received funding from the Centre for Excellence for CRVS—International Development Research Centre (IDRC), Ottawa, Canada. Award number: 108993- 001. ID, as part of the funder institution, was involved in the study design, data analysis, and the writing of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Günther Fink, Dr. Fabrizio Tediosi, and Dr. Mark Lambiris for his expert feedback on the systematic review.

Conflict of interest

RRB, CSF, DDS and DCM were employed by the Swiss Tropical Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland.

The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Author disclaimer

The statements in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of their organisations or funding agencies.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.ssph-journal.org/articles/10.3389/phrs.2022.1604560/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary File S1Quality Appraisal. Listing the quality appraisal ratings of each study using Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool.

Supplementary File S2PRISMA checklist. Addressing the evidence gap in the economic and social benefits of Civil Registration and Vital Statistics Systems: A Systematic Review, 2021. (Systematic review, Asia, America, Africa and Europe, 1910–2019).

Supplementary File S3Systematic review search strategy. Addressing the evidence gap in the economic and social benefits of Civil Registration and Vital Statistics Systems: A Systematic Review, 2021. (Systematic review, Asia, America, Africa and Europe, 1910–2019).

Abbreviations

COVID-19, Corona Virus Disease 2019; CRVS, Civil Registration and Vital Statistics; FGD, Focus Group discussions; LGBTQI, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex; LMICs, Low and Middle Income Countries; LNOB, Leave No One Behind; MMAT, Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool; SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals; SwissTPH, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute; United States, United States of America; 5q0, Child Mortality Risk.

References

1.

Resolution GA. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (2015). Geneva: United Nations.

2.

MillsSAbouzahrCKimJRassekhBMSarpongD. Civil Registration and Vital Statistics (CRVS) for Monitoring the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). World Bank (2017). Available from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/979321495190619598/Civil-registration-and-vital-statistics-CRVS-for-monitoring-the-Sustainable-development-goals-SDGS.

3.

MillsSLeeJKRassekhBM. An Introduction to the Civil Registration and Vital Statistics Systems with Applications in Low-And Middle-Income Countries. J Health Popul Nutr (2019) 38, 23. 10.1186/s41043-019-0177-1

4.

MikkelsenLPhillipsDEAbouZahrCSetelPWde SavignyDLozanoRet alA Global Assessment of Civil Registration and Vital Statistics Systems: Monitoring Data Quality and Progress. Lancet (2015) 386(10001):1395–406. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60171-4

5.

AbouZahrCMathengeGBrøndsted SejersenTMacfarlaneSB. Civil Registration and Vital Statistics: A Unique Source of Data for Policy. In: Macfarlane SB, AbouZahr C, editors. The Palgrave Handbook of Global Health Data Methods for Policy and Practice. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK (2019). p. 125–44. 10.1057/978-1-137-54984-6_7

6.

SetelPAbouZahrCAtuheireEBBratschiMCerconeEChinganyaOet alMortality Surveillance During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Bull World Health Organ (2020) 98(6):374. 10.2471/blt.20.263194

7.

AbouZahrC. What Is the True Human Toll of COVID-19? For Better Answers to This Critical Question, Strengthen Civil Registration Systems (2020). Available from: https://www.vitalstrategies.org/what-is-the-true-human-toll-of-covid-19-for-better-answers-to-this-critical-question-strengthen-civil-registration-systems/.

8.

EuroMOMO. European Mortality Monitoring Project. The European Monitoring of Excess Mortality for Public Health Action (EuroMOMO) Network (2020). Available from: https://www.euromomo.eu/.

9.

UN Legal Identity Agenda. Impact of COVID19. Maintaining CRVS During the COVID-19 Pandemic (2020). Available from: https://unstats.un.org/legal-identity-agenda/COVID-19/.

10.

PhillipsDEAbouZahrCLopezADMikkelsenLde SavignyDLozanoRet alAre Well Functioning Civil Registration and Vital Statistics Systems Associated with Better Health Outcomes?Lancet (2015) 386:1386–94. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60172-6

11.

AbouzahrCAzimiSYBersalesLGSChandramouliCHufanaLKhanKet alStrengthening Civil Registration and Vital Statistics in the Asia-Pacific Region: Learning from Country Experiences. Asia Pacific Popul J (2012) 29(1):39–73. 10.18356/a906ccf5-en

12.

HigginsJPGreenS. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chichester, England; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell (2011).

13.

MoherDLiberatiATetzlaffJAltmanDG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Plos Med (2009) 6(7):e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

14.

LiberatiAAltmanDGTetzlaffJMulrowCGøtzschePCIoannidisJPAet alThe PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies that Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol (2009) 62(10):e1–e34. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006

15.

NoyesJBoothAMooreGFlemmingKTunçalpÖShakibazadehE. Synthesising Quantitative and Qualitative Evidence to Inform Guidelines on Complex Interventions: Clarifying the Purposes, Designs and Outlining Some Methods. BMJ Glob Health (2019) 4(Suppl. 1):e000893. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000893

16.

HongQNPluyePBujoldMWassefM. Convergent and Sequential Synthesis Designs: Implications for Conducting and Reporting Systematic Reviews of Qualitative and Quantitative Evidence. Syst Rev (2017) 6(1):61. 10.1186/s13643-017-0454-2

17.

EPPI-Centre. Welcome to the EPPI-Reviewer 4 Gateway (2018). Available from: http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?alias=eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/er4.

18.

HongQPluyePFàbreguesSBartlettGBoardmanFCargoMet alMixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Version 2018. Canada: Canadian Intellectual Property Office (2018).

19.

AplandKBlitzBHamyltonCLagaayMlakshmanRYarrowE. Birth Registration and Children's Rights: A Complex Story. Plan International (2014). Available from: https://plan-international.org/files/global/publications/campaigns/birth-registration-research-full-report.pdf.

20.

FagernäsS. Protection Through Proof of Age. Birth Registration and Child Labor in Early 20th Century USA (2011).

21.

FagernäsS. Papers, Please! The Effect of Birth Registration on Child Labor and Education in Early 20th Century USA. Explor Econ Hist (2014) 52:63–92. 10.1016/j.eeh.2013.09.002

22.

BallJButtLBeazleyH. Birth Registration and Protection for Children of Transnational Labor Migrants in Indonesia. J Immigrant Refugee Stud (2017) 15:305–25. 10.1080/15562948.2017.1316533

23.

SeoBK. The Work of Inscription: Antenatal Care, Birth Documents, and Shan Migrant Women in Chiang Mai. Med Anthropol Q (2017) 31:481–98. 10.1111/maq.12342

24.

ChereniA. Underlying Dynamics of Child Birth Registration in Zimbabwe. Int J Child Rights (2016) 24:741–63. 10.1163/15718182-02404004

25.

BowlesJ. Identifying the Rich: The Political Economy of Civil Registration in Tanzania (2018). Available from: http://barrett.dyson.cornell.edu/NEUDC/paper_269.pdf (Accessed October 15, 2019).

26.

MusarandegaR. Integrated Human Rights and Poverty Eradication Strategy: The Case of Civil Registration Rights in Zimbabwe. Int Soc Sci J (2009) 60(197‐198):389–402. 10.1111/j.1468-2451.2010.01728.x

27.

KusumaningrumSBennounaCSiagianCAgastyaNLPM. Back to What Counts: Birth and Death in Indonesia. Jakarta, Indonesia: The Center on Child Protection Universitas Indonesia (PUSKAPA) in Collaboration with the Ministry of National Development Planning (BAPPENAS) and Kolaborasi Masyarakat dan Pelayanan untuk Kesejahteraan-KOMPAK (2016).

28.

CorbachoABritoSOsorio RivasR. Birth Registration and the Impact on Educational Attainment. IDB Working Paper Series (2012). Contract No: IDB-WP-345.

29.

JeongJBhatiaAFinkG. Associations Between Birth Registration and Early Child Growth and Development: Evidence from 31 Low- and Middle-Income Countries. BMC Public Health (2018) 18:673. 10.1186/s12889-018-5598-z

30.

ComandiniOCabrasSMariniE. Birth Registration and Child Undernutrition in Sub-Saharan Africa. Public Health Nutr (2016) 19(10):1757–67. 10.1017/s136898001500333x

31.

BritoSCorbachoAOsorioR. Does Birth Under-Registration Reduce Childhood Immunization? Evidence from the Dominican Republic. Health Econ Rev (2017) 7:14. 10.1186/s13561-017-0149-3

32.

GoldsenJBryanAEBKimH-JMuracoAJenSFredriksen-GoldsenKI. Who Says I Do: The Changing Context of Marriage and Health and Quality of Life for LGBT Older Adults. Geront (2017) 57:S50–S62. 10.1093/geront/gnw174

33.

RaifmanJMoscoeEAustinSBMcConnellM. Difference-in-Differences Analysis of the Association Between State Same-Sex Marriage Policies and Adolescent Suicide Attempts. JAMA Pediatr (2017) 171(4):350–6. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.4529

34.

RiggleEDBWickhamRERostoskySSRothblumEDBalsamKF. Impact of Civil Marriage Recognition for Long-Term Same-Sex Couples. Sex Res Soc Pol (2017) 14:223–32. 10.1007/s13178-016-0243-z

35.

MaduekweNIBanjoOOSangodapoMO. Data for the Sustainable Development Goals: Metrics for Evaluating Civil Registration and Vital Statistics Systems Data Relevance and Production Capacity, Illustrations with Nigeria. Soc Indic Res (2017) 140:101–24. 10.1007/s11205-017-1760-8

36.

Cobos MuñozDde SavignyDSorchikRBoKSHartJKwaVet alBetter Data for Better Outcomes: the Importance of Process Mapping and Management in CRVS Systems. BMC Med (2020) 18(1):67. 10.1186/s12916-020-01522-z

37.

ShattuckL. The Shattuck Report (1850). Available from: https://biotech.law.lsu.edu/cphl/history/books/sr (Accessed December 15, 2020).

38.

HawkeA. Birth Registration: Right from the Start. Florence, Italy: Innocenti Digest (2002).

39.

SzreterS. The Right of Registration: Development, Identity Registration, and Social Security-A Historical Perspective. World Develop (2007) 35(1):67–86. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2006.09.004

40.

MathersCDFatDMInoueMRaoCLopezAD. Counting the Dead and what They Died from: An Assessment of the Global Status of Cause of Death Data. Bull World Health Organ (2005) 83:171–7.

41.

RuzickaLKanePWunschG. Differential Mortality: Methodological Issues and Biosocial Factors. Oxford University Press (1995). Available from: https://econpapers.repec.org/bookchap/oxpobooks/9780198288824.htm.

42.

AbouZahrCClelandJCoullareFMacfarlaneSBNotzonFCSetelPet alThe Way Forward. Lancet (2007) 370(9601):1791–9. 10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61310-5

43.

FagernäsSOdameJ. Birth Registration and Access to Health Care: An Assessment of Ghana's Campaign Success. Bull World Health Organ (2013) 91(6):459–64. 10.2471/blt.12.111351

44.

CorrêaGVerstraetePSoundardjeeRShankarMPatersonCHamptonLet alImmunization Programmes and Notifications of Vital Events. Bull World Health Organ (2019) 97(4):306–8. 10.2471/blt.18.210807

45.

DriscollJ. Seeing Like A Subaltern: State-Building, Census Taking, & the Political Economy of Population Counts. Social Science Research Network (2016). 10.2139/SSRN.2825378

46.

MillsSAmponsahD. Economic Analysis of Producing Vital Statistics Using Civil Registration Data in Lao People's Democratic Republic. J Health Popul Nutr (2019) 38(Suppl. 1):20. 10.1186/s41043-019-0184-2

47.

NicholsEKRagunanthanNWRagunanthanBGebrehiwetHKamaraK. A Systematic Review of Vital Events Tracking by Community Health Agents. Glob Health Action (2019) 12(1):1597452. 10.1080/16549716.2019.1597452

48.

LuT-HLeeM-CChouM-C. Accuracy of Cause-Of-Death Coding in Taiwan: Types of Miscoding and Effects on Mortality Statistics. Int J Epidemiol (2000) 29(2):336–43. 10.1093/ije/29.2.336

49.

World Health Organization. Improving Mortality Statistics Through Civil Registration and Vital Statistics Systems: Strategies for Country and Partner Support - Outcome of a Technical Meeting. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2014).

50.

SumnerCKusumaningrumS. Indonesia’s Missing Millions: Erasing Discrimination in Birth Certification in Indonesia (CGD Policy Paper 064) (2015). Washington, DC: Center for Global Development.

51.

Ordóñez BustamanteDBracamonte BardálezP. El registro de nacimientos: Consecuencias en relación al acceso a derechos y servicios sociales y a la implementación de programas de reducción de pobreza en 6 países de Latinoamérica (2006). Available from: https://publications.iadb.org/handle/11319/6309 (Accessed January 14, 2020).

52.

Carter Center. Voter Identification Requirements and Public International Law: An Examination of Africa and Latin America. Research study. Atlanta: The Carter Center (2013).

53.

UNICEF. The "Rights" Start to Life: A Statistical Analysis of Birth Registration. Unicef (2005). New York.

54.

DahanMHanmerL. The Identification for Development (ID4D) Agenda: Its Potential for Empowering Women and Girls (2015). The World Bank. Available from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/22795 (Accessed January 10, 2020).

55.

Plan. Birth Registration in Emergencies: A Review of Best Practices in Humanitarian Action (2014). Report No: ISBN: 978-1-906273-63-7.

56.

CastanMGerberPGargettA. Indigenous Australians' Access to Birth Registration Systems: A Breach of International Human Rights Law?Aust J Hum Rights (2011) 17:55–89. 10.1080/1323238x.2011.11910895

57.

CalabroA. Registering the Births of Indigenous Australians: Has New South Wales Got it Right?Univ New South Wales L J (2013) 36:809–38. 10.3316/informit.736228515903213

58.

GuptaA. Hazme Visible Indigenous Children's Rights in Chiapas. DePaul J Soc Justice (2012) 5:379–91.

59.

SandersCBurnettK. A Case Study in Personal Identification and Social Determinants of Health: Unregistered Births Among Indigenous People in Northern Ontario. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2019) 16, 567. 10.3390/ijerph16040567

60.

Norwegian Refugee Council. Update on Marriage Registration for Refugees from Syria. Understanding the Procedures and Identifying the Challenges Faced by Refugees when Registering Marriages in Lebanon (2016). Available from: https://www.nrc.no/globalassets/pdf/reports/update-onmarriage-registration-for-refugees-from-syria.pdf (Accessed July 15, 2020).

61.

UN. Report of the Executive Committee of the Programme of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees on the Fifty-Fourth Session (2013). (29 September-3 October 2003).

62.

Cobos MuñozDAbouzahrCde SavignyD. The ‘Ten CRVS Milestones' Framework for Understanding Civil Registration and Vital Statistics Systems. BMJ Glob Health (2018) 3(2):e000673. 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000673

63.

NiambaL. Civil Registration and Vital Statistics (CRVS) Systems in the Face of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Literature Review. CRVS Working Paper Series, 3 (2021).

64.

AbouZahrCBratschiMWCerconeEMangharamASavignyDd.DincuIet alThe COVID-19 Pandemic: Effects on Civil Registration of Births and Deaths and on Availability and Utility of Vital Events Data. Am J Public Health (2021) 111(6):1123–31. 10.2105/ajph.2021.306203

65.

SDD. Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Operations of National Civil Registration and Vital Statistics (CRVS) Systems: 2020. Noumea, New Caledonia: Pacific Community (2020). p. 30.

66.

MillsSLeeJKRassekhBM. Benefits of Linking Civil Registration and Vital Statistics with Identity Management Systems for Measuring and Achieving Sustainable Development Goal 3 Indicators. J Health Popul Nutr (2019) 38(1):18. 10.1186/s41043-019-0178-0

67.

FuHSchweinfestS. COVID-19 Widens Gulf of Global Data Inequality, While National Statistical Offices Step Up to Meet New Data Demands. Data Blog (2020). [Internet].

Summary

Keywords

civil registration and vital statistics system, civil registration, vital statistics, birth registration/certification, death registration/certification, marriage registration/certification, divorce registration/certification

Citation

Revenga Becedas R, Sant Fruchtman C, Dincu I, De Savigny D and Cobos Muñoz D (2022) Addressing the Evidence Gap in the Economic and Social Benefits of Civil Registration and Vital Statistics Systems: A Systematic Review. Public Health Rev 43:1604560. doi: 10.3389/phrs.2022.1604560

Received

27 October 2021

Accepted

23 May 2022

Published

08 July 2022

Volume

43 - 2022

Edited by

Teresa Leão, University Porto, Portugal

Reviewed by

Carla AbouZahr, Consultant Vital Strategies, Switzerland

Carlos Matos, Universidade do Porto, Portugal

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Revenga Becedas, Sant Fruchtman, Dincu, De Savigny and Cobos Muñoz.