Abstract

Objective:

The systematic review reveals a lack of research on financing universal health coverage (UHC) in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). This study aims to examine the financing mechanisms used, identify the main challenges faced, and gather insights from successful experiences to inform future reforms in LMICs.

Methods:

We conducted a literature search across seven academic databases, limiting our systematic review to studies published in English and French between 2010 and 2022, which were then included in our qualitative analysis.

Results:

A total of 45 studies met the inclusion criteria—most used qualitative (n = 23) or documentary (n = 15) approaches. The majority (n = 37) were published between 2015 and 2022. Using Kutzin’s framework, we analyzed health financing functions in LMICs. Key challenges and lessons learned were summarized to improve understanding of ongoing financing issues and opportunities for reform.

Conclusion:

This study emphasizes key financing strategies and ongoing challenges in LMICs and provides specific recommendations for countries to prioritize reforms and address health financing gaps. The goal is to speed up progress toward UHC.

Introduction

Since 2005, when the World Health Organization (WHO) member states first adopted a resolution linking the concept of universal health coverage (UHC) to sustainable healthcare financing, global attention to health financing has grown significantly [1]. Several countries have joined this international movement to ensure their populations have equitable access to healthcare services without making their participation in healthcare financing regressive [2].

Although UHC became a global priority in 2010, many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have since made significant progress in developing financing systems to support this goal. Countries such as Thailand, Rwanda, and Costa Rica have demonstrated that progress toward UHC can be achieved through diverse models tailored to their specific national contexts [3]. Nevertheless, as the WHO highlighted in 2010, the majority of LMICs were still far from achieving UHC goals at that time [3]. UHC has subsequently received worldwide support for its importance and influence on other social determinants, such as poverty, social inclusion, and employment [4]. This is why the United Nations General Assembly adopted health as one of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and UHC as a health-related target under the SDGs [5]. However, the question that has been raised since 2010 is how health systems finance this major social project [3].

According to the latest reports published by the WHO and the World Bank, 1.4 to 1.9 billion people face catastrophic or impoverishing health expenses, most of whom are from LMICs [6, 7]. This critical situation is mainly caused by the rapid rise in out-of-pocket healthcare costs, which have surpassed other household expenses. Several factors explain this trend, including the inadequacy of financial protection mechanisms. COVID-19 has only worsened this situation by increasing the number of people skipping care and the financial strain of healthcare costs, especially for low-income populations worldwide [6]. Therefore, adopting an equitable healthcare financing model remains a significant challenge for achieving universal healthcare coverage [8].

Health financing plays a crucial role in any healthcare system, ensuring health equity and fully addressing the health needs of all citizens through its three interconnected functions: raising funds from various sources, pooling resources via prepayment systems, and purchasing healthcare services [9–11].

Health financing models in LMICs tend to rely on funding mechanisms that combine regressive sources (such as direct payments and external sources) at a high rate, with other progressive but limited methods, like tax revenues and contributions from social insurance schemes. These national financing models, developed in these countries, provide important lessons from successful experiences and common challenges faced by other nations [3, 8, 11]. In this regard, we focus this systematic review on LMICs according to the World Bank’s most recent classification (2021/2022).

Although the last decade has seen a remarkable increase in research on UHC financing issues, few reviews have used a systematic approach, and most have focused on specific geographic regions, such as sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia [12, 13]. Therefore, the value of this study lies in its comprehensive analysis of all interventions related to health financing in LMICs. The goal of this systematic review is to examine the mechanisms for financing universal health coverage in LMICs (revenue collection, pooling of resources, and purchasing), discuss the challenges faced by UHC financing models in these countries, and identify lessons learned from successful experiences for LMICs. To achieve these goals, the results section highlights the primary functions of health financing, while the discussion section addresses key challenges and lessons learned.

Methods

Protocol Reporting and Registration

This systematic literature review was carried out following the guidelines of the updated PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guide [14]. The completed PRISMA checklist is available in the Supplementary Material S1. The review was registered in the PROSPERO international registry of systematic reviews on 08 May 2023, with reference number ID: CRD42023422038.

Eligibility Criteria

Our eligibility criteria included original scientific studies, both qualitative and quantitative, as well as literature review articles, addressing any or all of the functions of health financing in LMICs with a universal health insurance program to achieve UHC. These functions encompass approaches to fundraising, resource pooling, and the service purchasing function, including provider payment methods and health service packages. We limited the selection to studies published in English and French from 2010, when the WHO released its report on financing universal healthcare, through 2022.

Information Sources

The literature searches were conducted in November 2022, and seven academic databases were consulted. Notably, PubMed, SCOPUS, WOS, Science Direct, Jstore, Springer, and Cochrane Library. We supplemented this search with an in-depth review of the references of relevant articles identified during the search.

Search Strategy

Search strategies were developed by the first author (HO) and reviewed by a team of three researchers, including the first author and two co-authors (EB, EA). Searches were carried out using the keywords “Universal health coverage,” “health financing functions,” and “low and middle income countries.” In addition, specific and general MeSH terms were added to capture other relevant articles indexed in the databases. Full search strategies are available in the Supplementary Material S2.

Selection Process

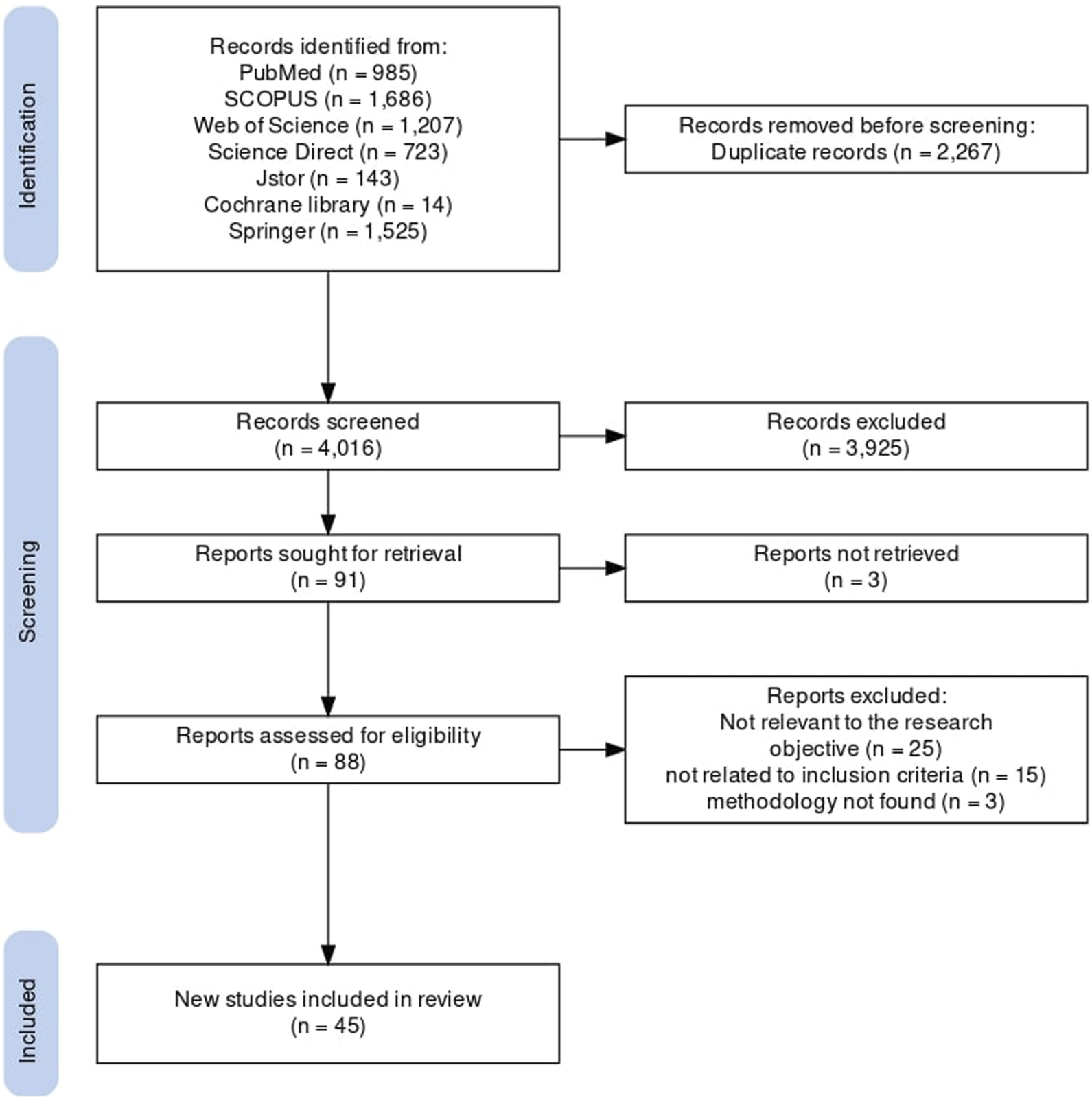

The article selection process is shown in Figure 1. The electronic search identified 6,283 articles. Records identified in the electronic databases were exported to the bibliographic reference management software “Zotero” for review by the research team.

FIGURE 1

PRISMA flowchart showing the selection and elimination of studies [15] (Systematic review of health financing functions for universal health coverage, Low- and Middle-lncome Countries, 2010–2022).

All duplicate articles (n = 2,267) were removed, and 4,016 articles were retained. Studies were selected in two stages. In the first stage, two reviewers (HO and EB) independently examined the titles and abstracts of the records identified in the searches to confirm their eligibility for the study objective. A total of 91 articles were retained. In a second step, we retrieved the full texts of the articles selected by the two reviewers (HO and EA) to confirm their eligibility based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Forty-six articles were then excluded, including 3 for which the full text could not be found. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus. A total of 45 studies met the inclusion criteria for this systematic review and were subsequently included in our qualitative analysis. A summary of the included studies is available in the Supplementary Material S3. No articles were retained by hand-searching the references of articles relevant to our research.

Data Collection Process

Data were extracted based on the results of studies considered relevant to this review and the essential elements of Kutzin’s (2001) conceptual framework for analyzing national healthcare financing arrangements [11]. Kutzin’s framework identifies three crucial functions of health financing - revenue collection, pooling, and purchasing of healthcare services - which together structure how financial resources are mobilized, managed, and used to progress towards UHC. The two reviewers (HO, EB) independently summarized the data from the included articles, and any disagreements were resolved through discussion between the research team until a consensus was reached. We used a standardized and tested data abstraction form in a spreadsheet using Microsoft Excel, to collect information on authors, year of publication, journal of publication, study setting, population, research objective and question, study design, description of health financing mechanisms, lessons learned, challenges faced, research limitations, conclusions and recommendations.

Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

The quality of studies deemed relevant to this study was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative checklist, the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) assessment tools, and the Mixed Methods Assessment Tool (MMAT). These tools assess and rank studies according to the relevance of their methodological elements (methodological design). They comprise several questions, each with the options “Yes,” “No,” or “Can’t Tell.” We took “Yes” to mean that the study included the answer to the question, and “No” and “Can’t Tell” to mean that the study did not include the answer to the question. Literature review articles, excluding systematic reviews, were excluded from this assessment.

The two reviewers (HO, EB) conducted the assessment independently, and any discrepancies were resolved through consensus. Studies were considered high quality if they met 80% or more of the CASP, JBI, or MMAT criteria, moderate quality if they met a score between 60% and 80%, and low quality if they met a score below 60%. All articles were included in the qualitative analysis, regardless of their final score, given the limited number of articles deemed relevant to our study.

Data Synthesis Strategy

We synthesized the extracted data using a thematic analysis. The conceptual framework described by Kutzin (2001) was used to derive the initial coding categories. In addition, challenges encountered, potential lessons learned, conclusions, and recommendations were added to the narrative summary. Two reviewers (HO and EA) were involved in this data synthesis process, and any disagreements between them were resolved by discussion between the research team.

Ethical Statement

This document is a systematic review and therefore does not require consideration of ethical issues.

Results

Study Characteristics

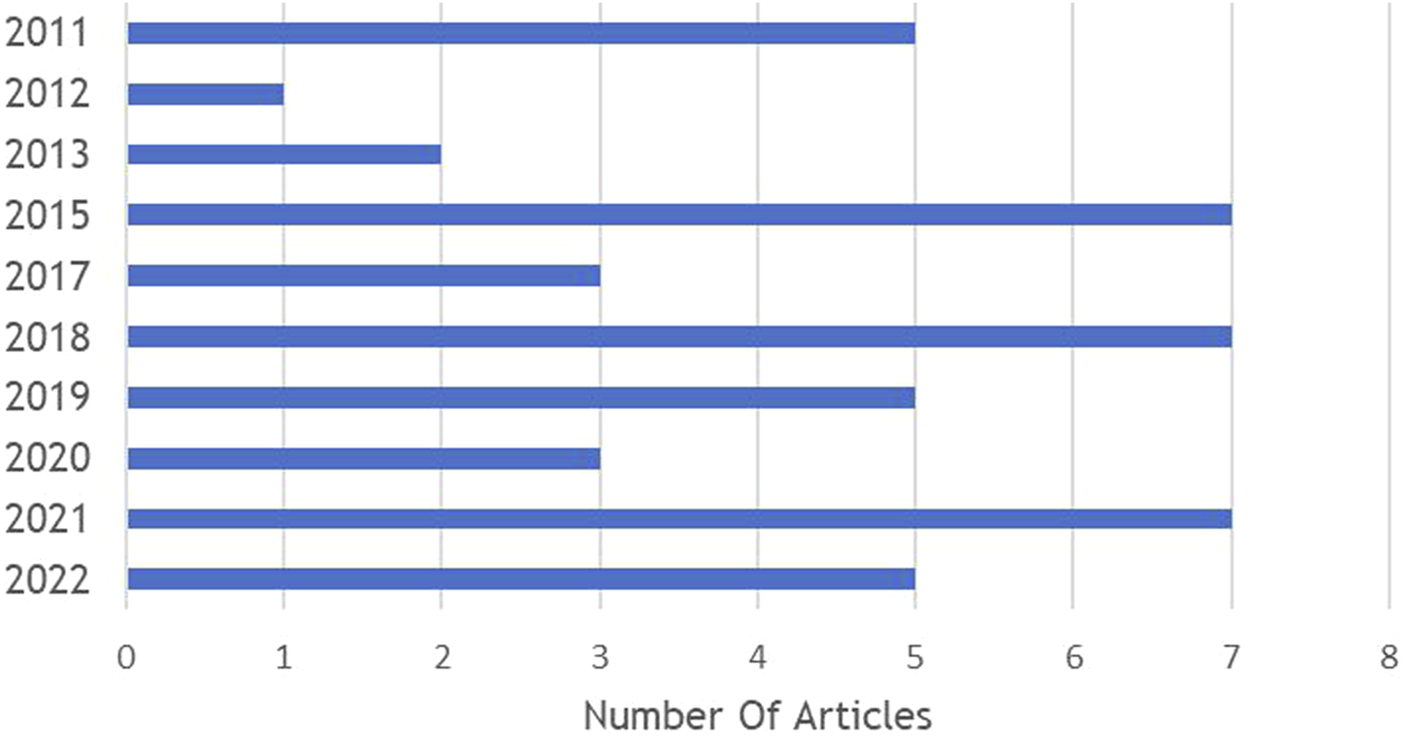

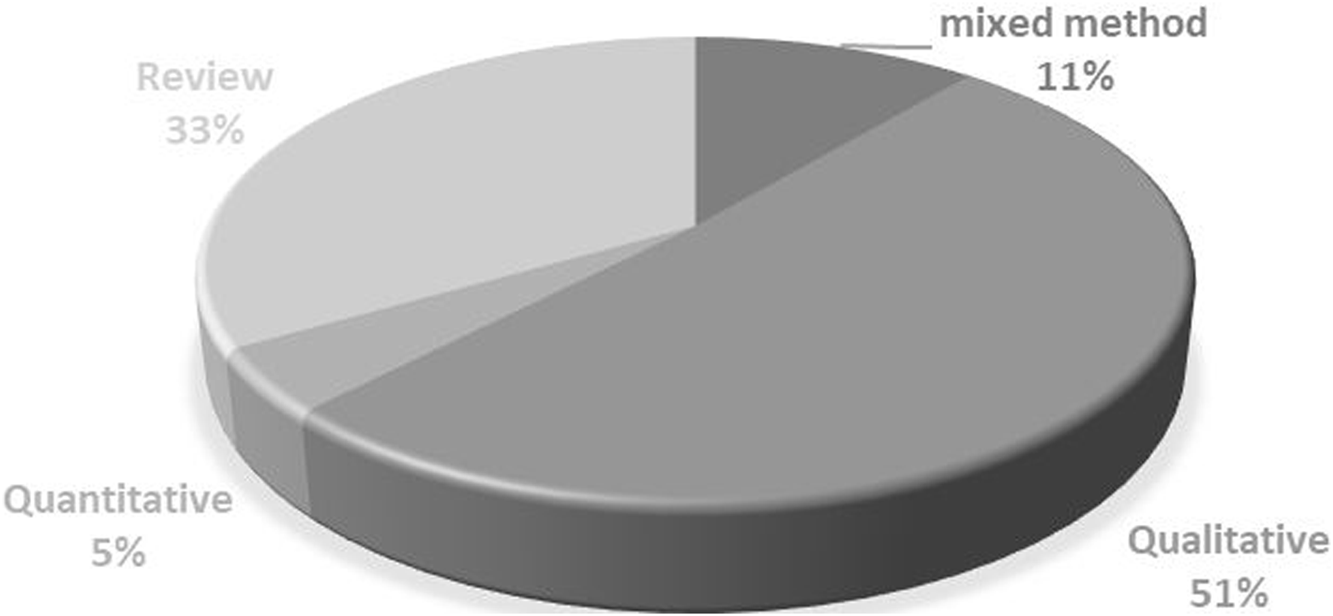

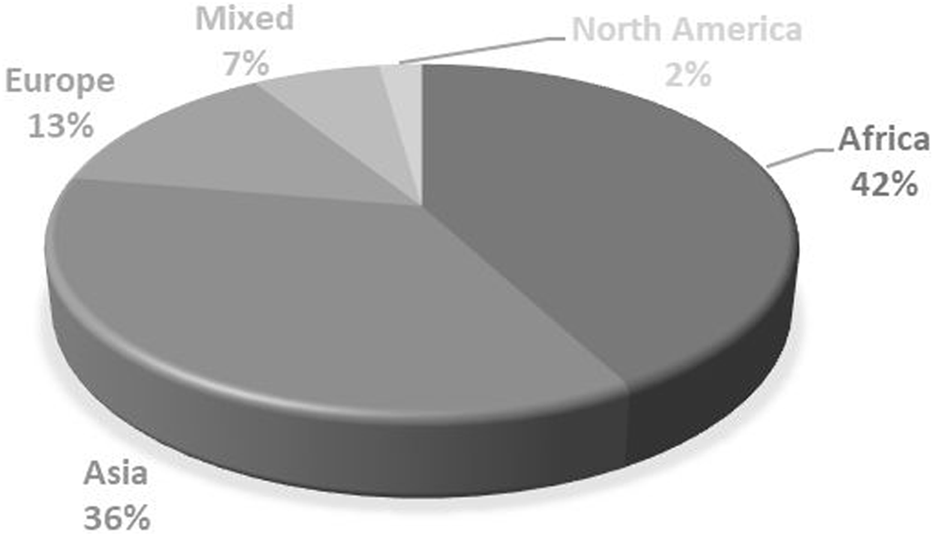

As shown in Figure 2, most articles were published between 2015 and 2022, totaling 37 out of the 45 articles included in this study. In terms of methodology, a trend emerged in favor of qualitative and documentary approaches, with 23 articles and 15 articles, respectively. This trend aligns with the aim of our study, which is to examine financing reforms in depth (Figure 3). Geographically, the majority of studies were carried out in Africa (42%) and Asia (36%), reflecting international efforts to promote universal healthcare in regions with high poverty rates (Figure 4).

FIGURE 2

Publication Years (Systematic review of health financing functions for universal health coverage, Low- and Middle-lncome Countries, 2010–2022).

FIGURE 3

Research Approaches (Systematic review of health financing functions for universal health coverage, Low- and Middle-lncome Countries, 2010–2022).

FIGURE 4

Geographical Distribution (Systematic review of health financing functions for universal health coverage, Low- and Middle-lncome Countries, 2010–2022).

Quality Assessment Results

Details of study quality are provided in the Supplementary Material S4. Although an assessment of study quality was conducted, it was decided not to consider this in interpreting the results because of the exploratory nature of the review. Overall, the studies included in this systematic review showed satisfactory methodological quality. Of the 45 studies included, 18 were rated as high quality, 11 as moderate quality, and 7 as low quality, based on the critical appraisal checklists. Nine review articles were descriptive and were not subjected to formal assessment. Despite differences in quality, all 45 studies were included in the thematic analysis due to their relevance to the review’s objectives and the limited literature available on the topic.

Fundraising

All health financing systems in the LMICs are considered mixed systems, utilizing financial resources from a variety of public and private sources [12, 16–32]. They utilize financial resources from various sources, including direct payments, taxes, and social health insurance contributions. Private financing of healthcare, characterized primarily by out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditures, plays a significant role in overall healthcare spending in several countries, despite its reputation for being regressive. In India, Nigeria, Nepal, Georgia, Vietnam, and the Philippines, for example, OOP spending is the primary source of healthcare funding [16, 22, 23, 26, 29, 31, 33]. In contrast, countries such as Rwanda, South Africa, Thailand, and Turkey are known for their low share of direct spending in total health expenditure (THE) [18, 19, 24]. As such, external funds, including donors, are an essential source in several LMICs, including Kenya, Nigeria, Rwanda, Tanzania, Cambodia, and Lao PDR [12, 19, 25, 31, 33–35].

In addition to private sources, public prepayment mechanisms, including public taxes and social health insurance, play a major role in healthcare financing in several countries such as Thailand, Turkey, Mexico, Costa Rica and China, which have succeeded in the role of these public sources as the main source of their healthcare financing system [20, 21, 24, 31, 32, 36, 37]. In other countries, such as Ghana [19, 38] and Vietnam [12], their social health insurance schemes rely mainly on earmarked taxes (i.e., indirect taxes).

Pooling Resources

The structuring of pooled funds for health services in the countries studied takes two main forms. On the one hand, some countries, such as Costa Rica [31], Turkey [39], and Indonesia [18], have merged their various health financing schemes into a single national health fund, financed mainly by public subsidies and member contributions. Similarly, other countries have established a single mutualization system, but one that explicitly includes both contributors and non-contributors in the same risk pool, thereby encouraging cross-subsidies. The latter approach is observed in Ghana, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Northern Macedonia [12, 19, 23, 28, 33].

On the other hand, other countries have multiple pooling systems with different forms of fragmentation. For example, Kenya [40], Nigeria [16], India [18], Iran [2, 24, 41], China [37, 42], Rwanda [19, 43], Tanzania [44], Georgia [29], Cambodia and Lao PDR [12] have fragmented risk-pooling systems based on segmentation of the population according to socio-economic status. In Thailand [21] and Mexico [32], in addition to the various pooling funds for the formal sector, there are other pooling funds for population groups outside the formal sector, with explicit coverage for all population groups. These include Thailand’s Universal Coverage System (UCS) and Mexico’s Social Health Protection System (SPSS), known as Seguro Popular until 2019, before being replaced by the program known as The Health Institute for Wellbeing (INSABI). Another form of risk pooling was observed in the Eastern European countries selected for our study, characterized by regional funds serving the population living in each distinct territory, due to the administrative divisions adopted by each country, including Russia [27] and Bulgaria [30].

Purchasing of Health Services (Including Provider Payment Methods and Benefit Packages)

Once the funds have been pooled, the final stage in the healthcare financing process is called purchasing. Indeed, the market structure of purchasers of healthcare services in the countries studied falls into two categories, those that use a single purchaser to channel all pooled resources to pay providers on behalf of the entire population, such as the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) in Ghana [18], the Vietnam Social Security (VSS) in Vietnam [23, 45], the Social Security Institution for the Health Sector (BPJS-K) in Indonesia [18], the Social Security Institution (SSI) in Turkey [39], the Social Security Fund (CCSS) in Costa Rica [31], the Health Insurance Fund (HIF) in North Macedonia [28] and the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) in Bulgaria [30] through the Regional Health Insurance Fund (RHIF), which constitutes a single purchaser covering the population living in each separate province.

The second model is characterized by the existence of several major purchasers in the same geographical area. There are countries where purchasing is carried out through two mechanisms: integrated purchasing, which generally occurs between the government, via the Minister of Health, and public providers, and contractual purchasing between health insurance schemes and public and/or private providers. Kenya [17, 34, 40, 46–49], Nigeria [35, 50–53], Rwanda [43], Russia [27], and Mexico [32] are examples. Other countries are adopting the demand-driven purchasing model for the entire population through social health insurance schemes. This is the case in China [20, 54], Thailand [21, 31, 55, 56], and Tanzania [44]. In India, private insurance companies act as purchasers of care on behalf of RSBY program members [22]. In Georgia, the Social Services Agency (SSA) purchases healthcare services on behalf of 95% of the population covered by the Universal Health Coverage Program (UHCP), while the wealthiest individuals purchase healthcare services through private insurance companies [29].

Due to the multitude of funding mechanisms, these countries are developing payment systems characterized by a combination of several payment methods, which vary according to the type of healthcare provider, services provided, and coverage scheme. These generally include fee-for-service, global budget, item-based budget, capitation, case-based payment including homogeneous diagnostic groups (DRGs), per diem, and salary. Over the years, various payment methods have been introduced to encourage providers to enhance their performance. In particular, performance-based payment (PBP) has been adopted in Rwanda [33, 43], Turkey [39], and North Macedonia [28].

Regarding the dimensions of the service package, the extent of service coverage in several countries is almost universal. These include the three national schemes in Thailand [31], the Community-Based Health Insurance (CBHI) and Rwanda Social Security Board (RSSB) programs in Rwanda [43], as well as national programs in Vietnam [23], Indonesia [12], and Turkey [36]. However, in Kenya [40], China [20], Tanzania [44], and Russia [27], purchasing organizations offer a varied range of services, differentiated according to the insurer’s status.

Discussion

This study aims to examine how LMICs have structured their health financing systems to meet UHC objectives. It focuses on the core financing functions—revenue collection, pooling, and purchasing—highlighting the mechanisms employed, the challenges faced, and the strategic choices made. The discussion that follows explores common patterns, context-specific barriers, and promising approaches across various countries.

Despite the considerable variation in regional contexts between LMICs, this analysis was not designed as a regional comparative study due to the uneven distribution of available studies. The discussion is organized around the essential functions of health financing (fundraising, pooling, and purchasing). It also incorporates illustrative examples at the country level to provide contextual information where necessary.

Fundraising

The studies included in this review often highlight the persistent challenges of resource mobilization, particularly the regressivity of direct payments, which hinders countries’ progress toward UHC [3, 57, 58]. This mechanism is often used as the primary source of funding for many of the countries studied. This observation can be attributed to the low level of public financing in THE, which represents a significant problem in most LMICs. Several studies have demonstrated the significance of public revenues in facilitating rapid progress towards universal healthcare in LMICs [59]. Thanks to government subsidies, China [60] and Thailand [61] have been able to extend medical coverage to populations that did not previously benefit from it. Furthermore, the long-term financial viability of mainly donor-funded health insurance systems in some of the countries studied is questionable [13]. In Cambodia, the Health Equity Fund (HEF) was funded until 2021 in equal parts by the government and donors. However, the donor commitment has come to an end, and responsibility now lies with the government [25]. It is therefore suggested to rely primarily on public funding sources, with a strong commitment from the government.

Pooling Resources

Concerning risk pooling, the results of our study highlight the high fragmentation of pre-payment systems in LMICs, compounded by limited cross-subsidization between risk pooling funds, leading to the creation of inequalities in access to care, with different levels of financial protection from one risk pool to another, as well as inequities between different territories in the country [12, 27, 31, 62]. Consequently, our results suggest consolidating all fragmented systems into a centralized fund, containing a diversification of health risks to maximize the capacity to redistribute resources. Several LMICs have endeavored to consolidate all fragmented prepayment systems, as shown by the successful experiences of Turkey and Indonesia, which were able to reduce inequalities in access to care by merging all risk pooling funds into a single fund on behalf of the entire population [63, 64]. Other international experiences demonstrate the benefits of consolidating fragmented systems in terms of equity and accessibility to care, control of healthcare expenditure, and savings in administrative costs [65–67]. However, many countries have made efforts to unify their pooling systems, but face several problems, including the large share of the informal sector, as in the case of Tanzania [19], as well as challenges in terms of institutional design and the capacity of administrative and information systems, which still prevent China from unifying its health insurance systems [37].

Purchasing Health Services

When it comes to healthcare purchasing, a number of challenges hinder active purchasing in the countries studied. Among these challenges, the weakness of institutional and governance arrangements for healthcare purchasing systems is a recurring issue. This weakness manifests itself in the absence of a sound regulatory framework, limited institutional capacity of purchasers, as well as poor budget management reflected in late disbursements and budget overruns. According to Adam Wagstaff (2010), the lack of regulation of national health insurance purchasers has a negative effect on the production of low-cost, high-quality care [68]. In addition, the low capacity of healthcare providers to respond to purchasers’ incentives is generally due to a lack of autonomy in the use of funds.

Other challenges linked to purchasing functions have been identified. Firstly, the absence of a guideline specifying the package of services according to the real needs of the population and national public health priorities, exacerbated by the variability of services offered, given the multiplicity of purchasers, contributes to the creation of inequities. Moreover, contractual agreements are often tacit, regardless of improvements in service quality. This observation aligns with previous work that highlights the lack of selective contracts in LMICs, which limits strategic purchasing [69]. At the same time, all countries use different provider payment systems, given the multiplicity of financing methods, and each payment method has its strengths and weaknesses depending on the context of use. Generally speaking, fee-for-service payment is considered the least strategic, as it can encourage over-consumption of resources and unnecessary practices. Performance-based payment can help motivate staff and improve provider performance, but it can also contribute to inefficiency, as is the case in Turkey [39]. Similarly, performance monitoring mechanisms are often weak, hampering strategic purchasing. In Kenya [47] and Nigeria [50], health data is still paper-based, limiting access to helpful information. In Rwanda [43], information systems are not interoperable, resulting in data duplication. According to Inke Mathauer et al. (2019), many LMICs have difficulty accessing useful health information, compounded by fragmented information systems limiting strategic purchasing [70]. The experience of countries that have successfully transitioned to strategic purchasing has shown significant progress in achieving UHC objectives [12, 13, 24, 28, 31, 39, 55, 56, 71]. This is reflected in the move to a single-payer purchasing model with selective contracts and incentive-based payment methods. These efforts need to be underpinned by strengthened governance, supported by a robust regulatory framework specifying the roles and responsibilities of purchasers and providers separately.

Study Limitations

This systematic review has certain limitations. First, the published literature tends to focus on specific regions rather than others, with most studies originating from a limited number of countries, including Kenya, Nigeria, China, and Thailand, which could influence our results and conclusions. Second, many studies have concentrated specifically on the third aspect of financing—the purchasing of healthcare services—at the expense of the other two functions, fundraising and resource pooling. Third, most of the studies included in our review are qualitative, likely due to the nature of our research question, which aims to explore in depth the financing mechanisms of universal health coverage in LMICs. Nevertheless, adding more quantitative studies would help provide a clearer picture of the key financing parameters and challenges that directly affect progress toward UHC goals. Finally, the current analysis focused on studies in English and French due to feasibility constraints, which may have excluded relevant data available in other languages used in LMICs.

Implications for Policy and Research

This study highlights persistent challenges and promising practices in health financing in LMICs. The findings can be a valuable resource for countries seeking to move towards universal health by informing policy decisions on health financing reforms. In addition, this synthesis can guide researchers in identifying unresolved issues related to the core functions of health financing, supporting further investigation and evidence-based strategies to improve the performance and equity of health system financing.

Conclusion

The results of this systematic review have enabled us to examine in depth the different approaches to financing universal health coverage in LMICs and to identify the main challenges in the field of health financing. The main conclusions drawn are the essential role played by public funds in providing financial protection to the vulnerable population and the extension of medical coverage to all categories, with the government’s share maintained over the long term. Furthermore, the unification of health insurance schemes is viewed as a key factor in promoting equitable access to healthcare services and a fair distribution of resources. In addition, establishing governance with a solid regulatory framework will strengthen the coordination and capabilities of all players involved in purchasing healthcare services. Finally, active purchasing plays a crucial role in improving the performance of the healthcare system, thanks to a selective contract between the purchaser and the provider, encouraging the provider to improve the quality of services in line with pre-established standards, and to control costs through the implementation of payment systems based on the achievement of service delivery targets.

Statements

Author contributions

The conceptualization of the project was done by OH and BE. Data curation was performed by OH, BE, and EA. Formal analysis was conducted by OH and EA. The methodology was developed by OH and EA. Project administration was carried out by OH and BE. Visualization of the results was done by OH, BE, and EA. The original draft of the manuscript was written by OH. Review and editing of the manuscript were done by OH and BE. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Author disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions or policies of the organizations with which they are affiliated.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.ssph-journal.org/articles/10.3389/phrs.2025.1607745/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

World Health Assembly 58. Sustainable Health Financing, Universal Coverage, and Social Health Insurance. Genève: World Health Organization (2005). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/20383 (Accessed July 2024).

2.

Ibrahimipour H Maleki MR Brown R Gohari M Karimi I Dehnavieh R . A Qualitative Study of the Difficulties in Reaching Sustainable Universal Health Insurance Coverage in Iran. Health Policy Plann (2011) 26(6):485–95. 10.1093/heapol/czq084

3.

World Health Organization. Health Systems Financing: The Path to Universal Coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization (2010). Available online at: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/44371 (Accessed July 2024).

4.

World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2022: Monitoring Health for the Sdgs, Sustainable Development Goals. Geneva: World Health Organization (2022). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/356584 (Accessed July 2024).

5.

United Nations General Assembly 70/1. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations (2015). Available online at: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf (Accessed July 2024).

6.

World Health Organization. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Tracking Universal Health Coverage: 2021 Global Monitoring Report. Geneva: World Health Organization (2021). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/357607 (Accessed July 2024).

7.

World Health Organization, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Global Monitoring Report on Financial Protection in Health 2021. Geneva: World Health Organization (2021). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/350240 (Accessed July 2024).

8.

Palas MJU Ashraf M Ray PK . Financing Universal Health Coverage: A Systematic Review. ITMR (2017) 6(4):133. 10.2991/itmr.2017.6.4.2

9.

World Health Organization McIntyre D Kutzin J . Health Financing Country Diagnostic: A Foundation for National Strategy Development. Genève. Genève, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2016). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/204283 (Accessed July 2024).

10.

World Health Organization. The World Health Report: 2000: Health Systems: Improving Performance. Genève. Genève, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2000). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42281 (Accessed July 2024).

11.

Kutzin J . A Descriptive Framework for country-level Analysis of Health Care Financing Arrangements. Health Policy (2001) 56(3):171–204. 10.1016/s0168-8510(00)00149-4

12.

Myint CY Pavlova M Thein KNN Groot W . A Systematic Review of the health-financing Mechanisms in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations Countries and the People’s Republic of China: Lessons for the Move Towards Universal Health Coverage. PLOS ONE (2019) 14(6):e0217278. 10.1371/journal.pone.0217278

13.

Ifeagwu SC Yang JC Parkes-Ratanshi R Brayne C . Health Financing for Universal Health Coverage in Sub-saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. Glob Health Res Policy (2021) 6(1):8. 10.1186/s41256-021-00190-7

14.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ (2021) 372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71

15.

Haddaway NR Page MJ Pritchard CC McGuinness LA . PRISMA2020: An R Package and Shiny App for Producing PRISMA 2020‐compliant Flow Diagrams, with Interactivity for Optimised Digital Transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst Rev (2022) 18(2):e1230. 10.1002/cl2.1230

16.

Uzochukwu BSC Ughasoro MD Etiaba E Okwuosa C Envuladu E Onwujekwe OE . Health Care Financing in Nigeria: Implications for Achieving Universal Health Coverage. Niger J Clin Pract (2015) 18(4):437–44. 10.4103/1119-3077.154196

17.

Barasa E Rogo K Mwaura N Chuma J . Kenya National Hospital Insurance Fund Reforms: Implications and Lessons for Universal Health Coverage. Health Syst Reform (2018) 4(4):346–61. 10.1080/23288604.2018.1513267

18.

Atim C Bhushan I Blecher M Gandham R Rajan V Davén J et al Health Financing Reforms for Universal Health Coverage in Five Emerging Economies. J Glob Health (2021) 11:16005. 10.7189/jogh.11.16005

19.

Fenny AP Yates R Thompson R . Strategies for Financing Social Health Insurance Schemes for Providing Universal Health Care: A Comparative Analysis of Five Countries. Glob Health Action (2021) 14(1):1868054. 10.1080/16549716.2020.1868054

20.

Li C Yu X Butler JRG Yiengprugsawan V Yu M . Moving Towards Universal Health Insurance in China: Performance, Issues and Lessons from Thailand. Social Sci and Med (2011) 73(3):359–66. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.002

21.

Damrongplasit K Melnick G . Funding, Coverage, and Access Under Thailand’s Universal Health Insurance Program: An Update After Ten Years. Appl Health Econ Health Policy (2015) 13(2):157–66. 10.1007/s40258-014-0148-z

22.

Devadasan N Seshadri T Trivedi M Criel B . Promoting Universal Financial Protection: Evidence from the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY) in Gujarat, India. Health Res Policy Sys (2013) 11(1):29. 10.1186/1478-4505-11-29

23.

Le QN Blizzard L Si L Giang LT Neil AL . The Evolution of Social Health Insurance in Vietnam and Its Role Towards Achieving Universal Health Coverage. Health Policy OPEN (2020) 1:100011. 10.1016/j.hpopen.2020.100011

24.

Hatam N Partovi Y Najibi S Marzaleh M Najibi S . Healthcare System Functions in Iran and Successful Developing Countries Regarding Access to Universal Health Coverage: A Comparative Study. IRANIAN RED CRESCENT MEDICAL JOURNAL (2021) 23(7):e712. 10.32592/ircmj.2021.23.7.710

25.

Kwon S Keo L . Social Health Protection in Cambodia: Challenges of Policy Design and Implementation. Int Soc Secur Rev (2019) 72(2):97–111. 10.1111/issr.12203

26.

Pokharel R Silwal PR . Social Health Insurance in Nepal: A Health System Departure Toward the Universal Health Coverage. Int J Health Plann Manage (2018) 33(3):573–80. 10.1002/hpm.2530

27.

Popovich L Potapchik E Shishkin S Richardson E Vacroux A Mathivet B . Russian Federation. Health System Review. Health Syst Transit (2011) 13(7):1–190.

28.

Milevska Kostova N Chichevalieva S Ponce NA van Ginneken E Winkelmann J . The Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia: Health System Review. Health Syst Transit (2017) 19(3):1–160.

29.

Richardson E Berdzuli N . Georgia: Health System Review. Health Syst Transit (2017) 19(4):1–90.

30.

Dimova A Rohova M Koeva S Atanasova E Koeva-Dimitrova L Kostadinova T et al Bulgaria: Health System Review. Health Syst Transit (2018) 20(4):1–230.

31.

McIntyre D Ranson MK Aulakh BK Honda A . Promoting Universal Financial Protection: Evidence From Seven low- and middle-income Countries on Factors Facilitating or Hindering Progress. Health Res Policy Sys (2013) 11(1):36. 10.1186/1478-4505-11-36

32.

González BMÁ Reyes Morales H Hurtado LC Balandrán A Méndez E . Mexico: Health System Review. Health Syst Transit (2020) 22(2):1–222.

33.

Lagomarsino G Garabrant A Adyas A Muga R Otoo N . Moving Towards Universal Health Coverage: Health Insurance Reforms in Nine Developing Countries in Africa and Asia. Lancet. (2012) 380(9845):933–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61147-7

34.

Munge K Mulupi S Barasa E Chuma J . A Critical Analysis of Purchasing Arrangements in Kenya: The Case of Micro Health Insurance. BMC Health Serv Res (2019) 19(1):45. 10.1186/s12913-018-3863-6

35.

Onwujekwe O Ezumah N Mbachu C Obi F Ichoku H Uzochukwu B et al Exploring Effectiveness of Different Health Financing Mechanisms in Nigeria; what Needs to Change and How Can It Happen? BMC Health Serv Res (2019) 19(1):661. 10.1186/s12913-019-4512-4

36.

Tatar M Mollahaliloğlu S Sahin B Aydin S Maresso A Hernández-Quevedo C . Turkey. Health System Review. Health Syst Transit (2011) 13(6):1–186.

37.

Meng Q Fang H Liu X Yuan B Xu J . Consolidating the Social Health Insurance Schemes in China: Towards an Equitable and Efficient Health System. The Lancet (2015) 386(10002):1484–92. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00342-6

38.

Domapielle MK . Adopting Localised Health Financing Models for Universal Health Coverage in Low and middle-income Countries: Lessons from the National Health Lnsurance Scheme in Ghana. Heliyon (2021) 7(6):e07220. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07220

39.

Ökem ZG Çakar M . What Have Health Care Reforms Achieved in Turkey? An Appraisal of the “Health Transformation Programme.”. Health Policy (2015) 119(9):1153–63. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.06.003

40.

Chuma J Okungu V . Viewing the Kenyan Health System Through an Equity Lens: Implications for Universal Coverage. Int J Equity Health (2011) 10(1):22. 10.1186/1475-9276-10-22

41.

Doshmangir L Bazyar M Rashidian A Gordeev VS . Iran Health Insurance System in Transition: Equity Concerns and Steps to Achieve Universal Health Coverage. Int J Equity Health (2021) 20(1):37. 10.1186/s12939-020-01372-4

42.

Yu H . Universal Health Insurance Coverage for 1.3 Billion People: What Accounts for China’s Success?Health Policy (2015) 119(9):1145–52. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.07.008

43.

Umuhoza SM Musange SF Nyandwi A Gatome-Munyua A Mumararungu A Hitimana R et al Strengths and Weaknesses of Strategic Health Purchasing for Universal Health Coverage in Rwanda. Health Syst Reform (2022) 8(2):e2061891. 10.1080/23288604.2022.2061891

44.

Kuwawenaruwa A Makawia S Binyaruka P Manzi F . Assessment of Strategic Healthcare Purchasing Arrangements and Functions Towards Universal Coverage in Tanzania. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HEALTH POLICY AND MANAGEMENT (2022) 11(12):3079–89. 10.34172/ijhpm.2022.6234

45.

Phuong NK Oanh TTM Phuong HT Tien TV Cashin C . Assessment of Systems for Paying Health Care Providers in Vietnam: Implications for Equity, Efficiency and Expanding Effective Health Coverage. Glob Public Health (2015) 10:S80–94. 10.1080/17441692.2014.986154

46.

Mbau R Kabia E Honda A Hanson K Barasa E . Examining Purchasing Reforms Towards Universal Health Coverage by the National Hospital Insurance Fund in Kenya. Int J Equity Health (2020) 19(1):19. 10.1186/s12939-019-1116-x

47.

Mbau R Barasa E Munge K Mulupi S Nguhiu PK Chuma J . A Critical Analysis of Health Care Purchasing Arrangements in Kenya: A Case Study of the County Departments of Health. Int J Health Plann Manage (2018) 33(4):1159–77. 10.1002/hpm.2604

48.

Munge K Mulupi S Barasa EW Chuma J . A Critical Analysis of Purchasing Arrangements in Kenya: The Case of the National Hospital Insurance Fund. Int J Health Policy Manag (2018) 7(3):244–54. 10.15171/ijhpm.2017.81

49.

Obadha M Chuma J Kazungu J Barasa E . Health Care Purchasing in Kenya: Experiences of Health Care Providers with Capitation and fee-for-service Provider Payment Mechanisms. Int J Health Plann Manage (2019) 34(1):e917–33. 10.1002/hpm.2707

50.

Ezenduka C Obikeze E Uzochukwu B Onwujekwe O . Examining Healthcare Purchasing Arrangements for Strategic Purchasing in Nigeria: A Case Study of the Imo State Healthcare System. Health Res Policy Sys (2022) 20(1):41. 10.1186/s12961-022-00844-z

51.

Ezenwaka U Gatome-Munyua A Nwankwor C Olalere N Orji N Ewelike U et al Strategic Health Purchasing in Nigeria: Investigating Governance and Institutional Capacities Within Federal Tax-Funded Health Schemes and the Formal Sector Social Health Insurance Programme. Health Syst Reform (2022) 8(2):e2074630. 10.1080/23288604.2022.2074630

52.

Etiaba E Onwujekwe O Honda A Ibe O Uzochukwu B Hanson K . Strategic Purchasing for Universal Health Coverage: Examining the purchaser–provider Relationship Within a Social Health Insurance Scheme in Nigeria. BMJ Glob Health (2018) 3(5):e000917. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000917

53.

Mbachu C Okeke C Obayi C Gatome-Munyua A Olalere N Ogbonna I et al Supporting Strategic Health Purchasing: A Case Study of Annual Health Budgets from General Tax Revenue and Social Health Insurance in Abia State, Nigeria. Health Econ Rev (2021) 11(1):47. 10.1186/s13561-021-00346-8

54.

Zhu K Zhang L Yuan S Zhang X Zhang Z . Health Financing and Integration of Urban and Rural Residents’ Basic Medical Insurance Systems in China. Int J Equity Health (2017) 16(1):194. 10.1186/s12939-017-0690-z

55.

Tangcharoensathien V Limwattananon S Patcharanarumol W Thammatacharee J Jongudomsuk P Sirilak S . Achieving Universal Health Coverage Goals in Thailand: The Vital Role of Strategic Purchasing. Health Policy Plann (2015) 30(9):1152–61. 10.1093/heapol/czu120

56.

Patcharanarumol W Panichkriangkrai W Sommanuttaweechai A Hanson K Wanwong Y Tangcharoensathien V . Strategic Purchasing and Health System Efficiency: A Comparison of Two Financing Schemes in Thailand. PLoS One (2018) 13(4):e0195179. 10.1371/journal.pone.0195179

57.

Lagarde M Palmer N . The Impact of User Fees on Access to Health Services in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2011) 2011(4):CD009094. 10.1002/14651858.CD009094

58.

Yates R . Universal Health Care and the Removal of User Fees. Lancet (2009) 373(9680):2078–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60258-0

59.

Acharya A Vellakkal S Fiona T Satija A Burke M Ebrahim S . Impact of National Health Insurance for the Poor and the Informal Sector in low- and middle-income Countries: A Systematic Review. London, United Kingdom: EPPI Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London (2012).

60.

Yip W Hsiao WC . The Chinese Health System at A Crossroads. Health Aff (2008) 27(2):460–8. 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.460

61.

Glassman A Temin M . Millions Saved: New Cases of Proven Success in Global Health. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development (2016). p. 300.

62.

Rao KD Petrosyan V Araujo EC McIntyre D . Progress Towards Universal Health Coverage in BRICS: Translating Economic Growth into Better Health. Bull World Health Organ (2014) 92(6):429–35. 10.2471/BLT.13.127951

63.

Menon R Mollahaliloglu S Postolovska I . Toward Universal Coverage: Turkey’s Green Card Program for the Poor. Washington DC: The World Bank (2013).

64.

Agustina R Dartanto T Sitompul R Susiloretni KA Suparmi AEL Wirawan F et al Universal Health Coverage in Indonesia: Concept, Progress, and Challenges. The Lancet (2019) 393(10166):75–102. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31647-7

65.

Glied S . Single Payer as a Financing Mechanism. J Health Polit Policy L (2009) 34(4):593–615. 10.1215/03616878-2009-017

66.

Mathauer I Vinyals Torres L Kutzin J Jakab M Hanson K . Pooling Financial Resources for Universal Health Coverage: Options for Reform. Bull World Health Organ (2020) 98(2):132–9. 10.2471/BLT.19.234153

67.

Cheng TM . Reflections on the 20th Anniversary of Taiwan’s Single-Payer National Health Insurance System. Health Aff (2015) 34(3):502–10. 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1332

68.

Wagstaff A . Social Health Insurance Reexamined. Health Econ (2010) 19(5):503–17. 10.1002/hec.1492

69.

Cashin C Gatome-Munyua A . The Strategic Health Purchasing Progress Tracking Framework: A Practical Approach to Describing, Assessing, and Improving Strategic Purchasing for Universal Health Coverage. Health Syst and Reform (2022) 8(2):e2051794. 10.1080/23288604.2022.2051794

70.

Mathauer I Dale E Jowett M Kutzin J . Purchasing Health Services for Universal Health Coverage: How to Make It More Strategic?Genève, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2019).

71.

Amporfu E Agyei-Baffour P Edusei A Novignon J Arthur E . Strategic Health Purchasing Progress Mapping: A Spotlight on Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme. Health Syst Reform (2022) 8(2):e2058337. 10.1080/23288604.2022.2058337

Summary

Keywords

health financing functions, fundraising, pooling, purchasing of health services, universal health coverage

Citation

Hajji O, El Abbadi B and Akhnif EH (2025) Systematic Review of Financing Functions for Universal Health Coverage in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Reforms, Challenges, and Lessons Learned. Public Health Rev. 46:1607745. doi: 10.3389/phrs.2025.1607745

Received

10 July 2024

Accepted

13 August 2025

Published

23 September 2025

Volume

46 - 2025

Edited by

Tess Bardy, University of Lucerne, Switzerland

Reviewed by

Anung Ahadi Pradana, Mitra Keluarga Hospital, Indonesia

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Hajji, El Abbadi and Akhnif.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms. PHR is edited by the Swiss School of Public Health (SSPH+) in a partnership with the Association of Schools of Public Health of the European Region (ASPHER)+

*Correspondence: Othmane Hajji, hajjiothmane62@gmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.