Abstract

Objectives: This study intends to evaluate Dhaka city slum dwellers’ responses to Dengue fever (DF).

Methods: 745 individuals participated in a KAP survey that was pre-tested. Face-to-face interviews were performed to obtain data. Python with RStudio was used for data management and analysis. The multiple regression models were applied when applicable.

Results: 50% of respondents were aware of the deadly effects of DF, its common symptoms, and its infectious nature. However, many were unaware that DF could be asymptomatic, a previously infected person could have DF again, and the virus could be passed to a fetus. Individuals agreed that their families, communities, and authorities should monitor and maintain their environment to prevent Aedes mosquito breeding. However, overall 60% of the study group had inadequate preventative measures. Many participants lacked necessary practices such as taking additional measures (cleaning and covering the water storage) and monitoring potential breeding places. Education and types of media for DF information were shown to promote DF prevention practices.

Conclusion: Slum dwellers lack awareness and preventative activities that put them at risk for DF. Authorities must improve dengue surveillance. The findings suggest efficient knowledge distribution, community stimulation, and ongoing monitoring of preventative efforts to reduce DF. A multidisciplinary approach is needed to alter dwellers’ behavior since DF control can be done by raising the population’s level of life. People and communities must perform competently to eliminate vector breeding sites.

Introduction

Dhaka, the capital city of Bangladesh, has had a rapid population increase and density [1]. Migration caused by climate change has exacerbated these concerns [2]. Dengue fever (DF) and the COVID-19 pandemic have reached alarming levels in the city [3–9]. DF, a neglected tropical disease, wreaks havoc on developing countries, particularly in Asia [10, 11]. It was initially identified in 1780, but the first occurrence of dengue in Bangladesh was reported in 1964 under the name “Dhaka/Dacca fever” [12]. Dengue cases were then intermittently recorded in Bangladesh, primarily in Dhaka [12]. Additionally, a rapid spike in dengue cases was seen after the year 2000, with 2019s large number of infections resulting in several fatalities [13]. It has been a burden on the country, particularly Dhaka, which was severely affected by a rapid dengue outbreak [3]. This densely populated metropolis accounted for over half of the country’s dengue cases in 2019 [13]. Studies indicate that a high population density, increasing unplanned development, limited dengue surveillance operations, contempt for dengue protective behavior, and climate change might all lead to a significant dengue outbreak in the city [14, 15]. In addition, research predicted that this city would be the core of the country’s significant dengue outbreaks [16]. Moreover, according to research, the rapid development of the dengue outbreak across the country in 2019 was driven by the huge migration of dengue-infected individuals (many of whom were anticipated to be asymptomatic) from Dhaka to other cities in the country [3]. It is considered that Bangladesh’s ailing healthcare system has led to a considerable underreporting of Dengue cases [17]. Individuals are concerned about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic because the city has already been severely affected. Even though dengue and COVID-19 include fever symptoms and asymptomatic cases, the number of reported dengue cases during the pandemic cannot be ignored [18]. Consequently, local inhabitants have battled to limit the disease’s catastrophic effects.

While there is no effective vaccination for DF, health habits such as adherence to accurate knowledge, having a good attitude, and sticking to safe practices may pave the road for DF eradication [19]. Changes in individual and community behavior, as well as appropriate government support for DF can help reduce the growing prevalence of dengue in Dhaka and, by extension, throughout the country. DF has already been the subject of several studies in Bangladesh [3, 6, 15, 20]. However, knowing the resident’s knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) of DF is critical for efficient vector-borne disease control [21]. The KAP model, developed in the 1950s, has been widely used to assess survey respondents’ understanding of a subject [8, 9, 22, 23]. The simple design, normative data, and precise report make this survey approach convenient [24]. Additionally, it is assumed to demonstrate the interaction between respondents’ KAP domains [25]. Communities may be better able to prepare for and respond to public health emergencies if the KAP level is known. In addition, such research may help to create interventions that encourage desired behavioral changes [26]. Several web-based research of KAP among Dhaka’s general population and university students showed a statistically significant correlation between socio-demographic data and KAP about DF [6, 20]. However, despite the increased risk of DF among slum dwellers [27–29], there is a lack of research on KAP concerning DF in Dhaka’s slums. According to the KAP survey, we can assess the level of DF preparedness for this vulnerable group. The findings can assist the policies and strategies that reduce the risk of DF for these vulnerable people.

Today’s megacities are extremely diverse, with substantial slum populations posing issues for community health and healthcare [30]. Depending on where you reside in a major urban area, there might be vast variances in health conditions. In general, urban health is better than rural health, but in particular areas, urban health might be poorer [31]. Certain infectious diseases have emerged and re-emerged due to the urban environment’s constant change. Pathogens adapted to urban conditions from rural environments can spread rapidly and place a higher load on healthcare systems [32]. Bangladesh’s slums are densely populated urban areas with substandard housing and squalor. According to the findings of a study, slum areas are afflicted with DF [27]. The density of Aedes aegypti mosquito larvae has been found to be four times higher than the normal level in the slums of the city [28, 29]. Moreover, given the recent increase in dengue mortality inside Dhaka, it is essential to evaluate the dengue-associated KAP of city slum dwellers to establish efficient vector control and monitoring techniques. This study aimed to assess the KAP towards DF among Dhaka’s slum dwellers. This study may provide international, national, and municipal authorities, as well as non-governmental and social groups regulating the DF with crucial baseline data.

Methods

Study Design and Population

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a cross-sectional study was performed. The study is delimited to Dhaka, the city with the most slum residents in Bangladesh [33]. This study was conducted as part of a research project approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Bangladesh University of Professionals, Dhaka, Bangladesh (BUP REC0907/2019). It evaluated all relevant ethical concerns. The aims and ethical problems of the survey were articulated on the questionnaire’s cover page. Consent was obtained from respondents, who remained anonymous.

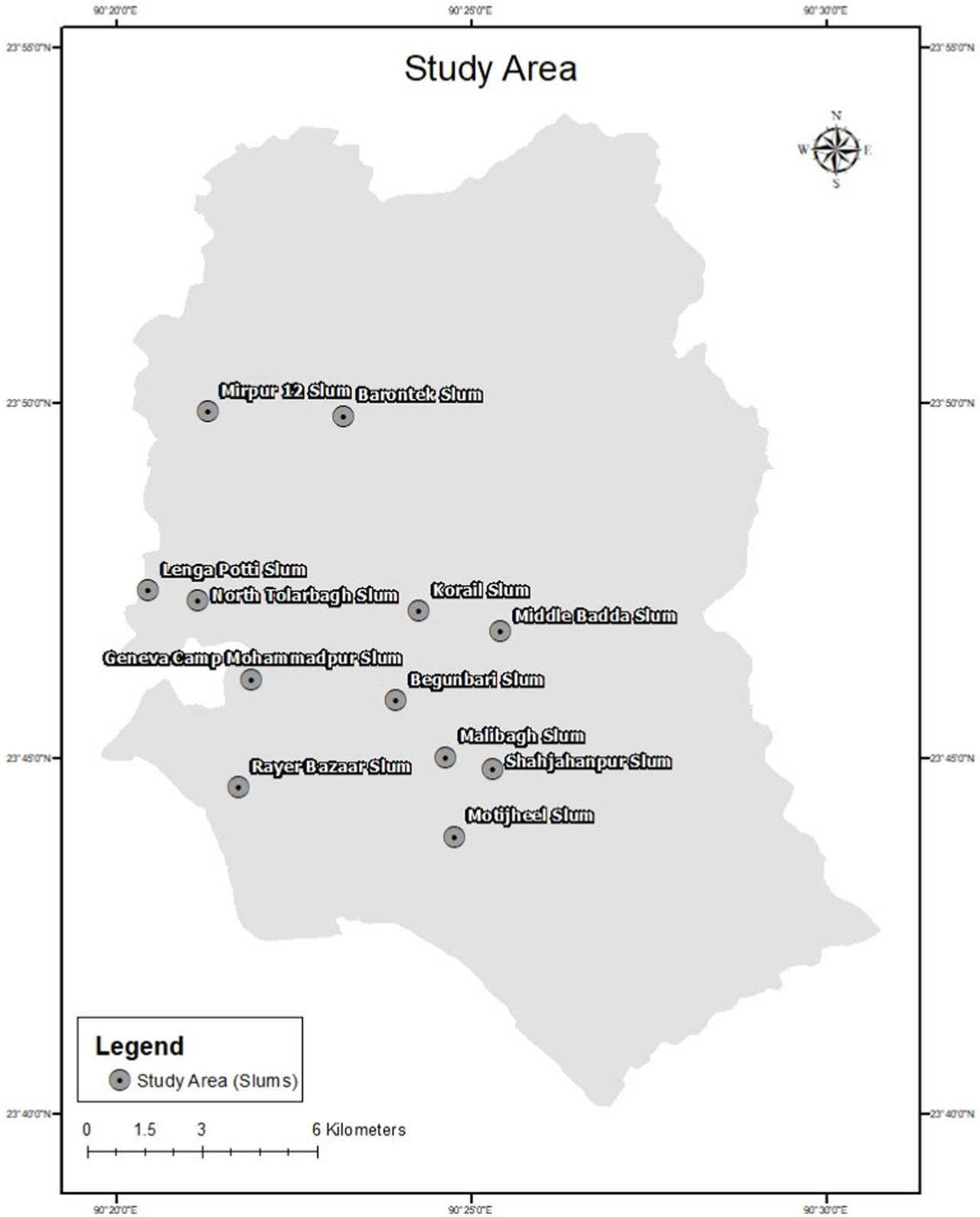

Over one-third of Dhaka’s population lives in one of the city’s 5,000 slums or informal settlements, and slum populations are rising at more than double the rate of urban areas overall [33]. One study indicated that more than 37.0% of the population of this city lives in slums [34]. Slums usually have no access to piped water and temporary containers like drums and earthen jars commonly store water where Aedes mosquito lays eggs [35]. Inadequate supplies of piped water and an absence of proper waste management in most locations of Dhaka result in abundant indoor and outdoor mosquito breeding sites [36]. Most slum dwellers are immigrants living in economically depressed conditions [37]. In addition to lacking permanent work, their health and physical conditions are substandard. We have surveyed 12 slums in Dhaka city (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

The study area (Dhaka, Bangladesh. 2021).

Questionnaire

The Bangladeshi viewpoint was considered when adapting and developing the draft questionnaire based on a thorough review of prior research [15, 21, 38–41]. In order to pre-test the questionnaire, experts’ comments and a pilot survey were conducted after that. A final questionnaire was prepared with slum dwellers in consideration. The survey was administered in Bengali, the local language. It consisted of two primary elements: respondent information and KAP sections. There were 32 items in the KAP section. There have been 13 closed-ended questions in the knowledge section (DF is an infectious disease, it can cause death, common symptoms of the disease, vector type, phenotype of the mosquito, breeding sites of the mosquito, biting time, DF risk during pregnancy, and DF infection characteristics). The scoring range was from 0 to 1, with the “Maybe” option (if applicable) receiving a score of 0.50. The attitude section contained 9 closed-ended items with a 5-point Likert scale (Strongly agree = 5, Agree = 4, Neutral = 3, Disagree = 2, and Strongly disagree = 1). It had items such as the responsibility to ensure the absence of vector mosquitoes and breeding sites; Regular DF surveillance activities; Community commitment to control the outbreak; Participation in DF control public activity; Taking immediate treatment; and Concerning DF. The final practice section contained 10 items with Yes/No answers and a 0–1 score range (communicating the authority for fogging, using mosquito repellent and coil or mosquito-killing tools, checking the mosquito breeding sites, covering and cleaning the water containers, cleaning the plant pots, visiting a hospital for treatment, and following good practices during a pandemic). We calculated Cronbach’s alpha for internal consistency in the KAP domain, where knowledge = 0.84, attitude = 0.88, practice = 0.67, and overall KAP = 0.87. Cronbach’s alpha >0.60 suggests an adequate level, whereas >0.80 implies an outstanding one [42].

Sampling Design

We have followed the non-probability, purposive, and convenience sampling techniques. Convenience sampling is a non-probability sampling technique in which units are included in the sample because they are the most accessible to the researcher [43]. It may be due to geographical accessibility, availability at a specific moment, or a willingness to engage in the study. First, we chose a slum based on its accessibility (to people and known persons who live in slums) and DF risk (based on previous reports). For instance, the disease control section of the Directorate General of Health Services of Bangladesh performed a survey from the end of July to the beginning of August 2019, and they found that the number of Aedes mosquito larvae was four times higher than they had anticipated at the Shajahanpur slum [28]. In our prior study on fire preparedness in Dhaka’s slums, we employed a similar sampling technique [44]. We only selected individuals over 18 years who resided in a particular slum and were accessible. Finally, we maintained a minimum number of participants (around 50) from each of our selected slums. The sample size was calculated using Yamane’s formula [45]:where n = sample size, N = population, e = error tolerance.

Approximately 4 million slum dwellers were found in Dhaka city [33]. Therefore, following this population and 0.05 error tolerance, the required sample size was around 400.

Data Collection

The survey was conducted from January to March of 2021. There was a face-to-face interview. Consent was taken. The data was double-checked for anomalies.

Data Management and Analysis

Python (version 2.7; Beaverton, OR 97008, United States) and RStudio (version 1.2.5042; Boston, MA, United States) [46, 47] were used for data analysis and management. All statistical analysis was performed with 95% CI. When applicable, descriptive analyses (frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation) were calculated. First, the average score was calculated to ensure that the same scale was utilized throughout the study. It was accomplished by first computing the section’s overall score by adding the component scores. The section’s mean score was then calculated by dividing the total score by the number of items in the section (Eq. 1). In the case of attitude, this number is again divided by 5 (this section had 5 scales). Consequently, all three portions were scaled the same (0–1 score range).Where i is for ith item’s score and n is the total number of items.

Spearman’s rank correlation was applied to assess the correlation in the KAP domain. In multiple linear regression analyses, predictors (p < 0.05) from univariate linear regression analyses were used after screening.

Results

Respondent’s Characteristics

We examined 745 responses in the final analysis. Table 1 reveals that most respondents were around 18–35 years (around 70%). The male respondents (54%) were more than the female respondents (46%). Most respondents were married (71%) and living with their families (84%). More than 50% did not have any education. Many indicated they have limited income sources, such as day workers, rickshaw pullers, vehicle drivers, home maids, etc. Therefore, we considered them workers with limited income compared to others without any earning source. Regarding preferred media for DF information, they primarily used electronic media such as Television, Radio (48%), and their family members or community (36%).

TABLE 1

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| 1. Age (year) | |

| 18–25 | 265 (35.57) |

| 26–35 | 276 (37.05) |

| 36–45 | 131 (17.58) |

| More than 45 | 73 (9.80) |

| 2. Gender | |

| Male | 402 (53.96) |

| Female | 343 (46.04) |

| 3. Marital status | |

| Married | 527 (70.74) |

| Unmarried | 132 (17.72) |

| Other (Separated, Divorced) | 86 (11.54) |

| 4. Living with family | |

| Yes | 627 (84.16) |

| No | 118 (15.84) |

| 5. Education | |

| ≥ Primary level | 363 (48.72) |

| No education | 382 (51.28) |

| 6. Occupation | |

| Worker | 533 (71.54) |

| No work | 212 (28.46) |

| 7. COVID-19 has negative impact on dengue fever surveillance activities | |

| Yes | 237 (31.81) |

| Maybe | 356 (47.79) |

| No | 152 (20.40) |

| 8. Media used for dengue fever information | |

| Electronic media (Television, Radio) | 361 (48.46) |

| Social media | 94 (12.62) |

| People (community, family members) | 269 (36.11) |

| Others | 21 (2.82) |

Characteristics of the respondents (n = 745) (Dhaka, Bangladesh. 2021).

Knowledge Regarding Dengue Fever

The knowledge, attitudes, and practices about DF are displayed in Table 2. Over half of the slum dwellers (57%) knew that dengue is an infectious disease. In comparison, around 54% were aware of the common symptoms of dengue fever, including rash, headache, high fever, joint pain, muscle pain, nausea, etc. Only 26% knew of the asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic DF cases. Additionally, almost 60% of them were aware of deaths caused by the DF. However, few (29%) indicated familiarity with the DF situation for multiple occurrences in the same individual, and fewer (23%) were aware that DF could be severe the second time. Additionally, roughly 19% knew the dengue virus could be transmitted from an infected pregnant woman to the fetus. Approximately 40% of the participants knew the likely breeding location and frequency of insect bites. However, only 11% knew the number for the health call center.

TABLE 2

| Knowledge | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Items | Correct response [n (%)] | ||||||

| K1 | Dengue is an infectious disease | 422 (56.64) | ||||||

| K2 | Dengue fever can cause death | 445 (59.73) | ||||||

| K3 | Common symptoms of dengue infection are rash, headache, high fever, joint pain, muscle pain, nausea | 400 (53.69) | ||||||

| K4 | People can have dengue virus even without any (or mild symptoms) symptoms | 197 (26.44) | ||||||

| K5 | One person can be infected with dengue virus more than once | 214 (28.72) | ||||||

| K6 | Second time dengue infection can be severe | 168 (22.55) | ||||||

| K7 | Dengue virus can be transmitted from infected pregnant mother to fetus | 143 (19.19) | ||||||

| K8 | Aedes mosquito type by which dengue virus is transmitted | 377 (50.60) | ||||||

| K9 | Aedes mosquito has stripes on the body | 379 (50.87) | ||||||

| K10 | I know the breeding place of Aedes mosquitoes | 312 (41.88) | ||||||

| K11 | I know that Aedes mosquito breed both indoor and outdoor | 317 (42.55) | ||||||

| K12 | I know that Aedes mosquito usually bites early in the morning and late evening | 289 (38.79) | ||||||

| K13 | I know health call center number of the authority | 79 (10.60) | ||||||

| Attitude | ||||||||

| No | Items | a SA [n (%)] | a A [n (%)] | a N [n (%)] | a DA [n (%)] | a SDA [n (%)] | ||

| A1 | It is my obligation to ensure that there are no Aedes eggs or larvae in the vicinity of my home | 95 (12.75) | 238 (31.95) | 224 (30.07) | 180 (24.16) | 08 (1.07) | ||

| A2 | My relatives and neighbors should clean Aedes mosquito breeding sites weekly, such as water containers, storage tanks, and plant pots | 73 (9.80) | 277 (37.18) | 230 (30.87) | 159 (21.34) | 06 (0.81) | ||

| A3 | Only chemical fogging by the authority is insufficient to prevent dengue infection; the authority must also destroy possible breeding grounds | 94 (12.62) | 292 (39.19) | 225 (30.20) | 124 (16.64) | 10 (1.34) | ||

| A4 | We should routinely examine the dengue situation or hotspots in our neighborhood | 80 (10.74) | 268 (35.97) | 212 (28.46) | 175 (23.49) | 10 (1.34) | ||

| A5 | Even when an outbreak is not occurring, it is vital to maintain eliminating mosquito breeding grounds | 75 (10.07) | 294 (39.46) | 217 (29.13) | 148 (19.87) | 11 (1.48) | ||

| A6 | Dengue outbreak in my area may be contained if every family removes mosquito breeding grounds | 72 (9.66) | 292 (39.19) | 210 (28.19) | 162 (21.74) | 09 (1.21) | ||

| A7 | I will participate in a public action for dengue control or mosquito breeding place elimination | 72 (9.66) | 215 (28.86) | 234 (31.41) | 204 (27.38) | 20 (2.68) | ||

| A8 | If a member of my family exhibits symptoms of dengue fever, I will bring him or her to a doctor immediately for treatment | 76 (10.20) | 323 (43.36) | 209 (28.05) | 128 (17.18) | 09 (1.21) | ||

| A9 | I am concerned about dengue even in the Coronavirus pandemic time | 77 (10.34) | 275 (36.91) | 244 (32.75) | 138 (18.52) | 11 (1.48) | ||

| Practices | ||||||||

| Items | Yes [n (%)] | No [n (%)] | ||||||

| P1 | I call Municipality authority for fogging | 29 (3.89) | 716 (96.11) | |||||

| P2 | I follow different ways (aerosol and/or liquid mosquito repellent and/or mosquito coil and/or electrical mosquito mat and/or mosquito bed net) to reduce mosquito | 613 (82.28) | 132 (17.72) | |||||

| P3 | I wear proper cloth to protect from mosquito biting | 149 (20.00) | 596 (80.00) | |||||

| P4 | I take extra precautions when I travel, to protect from mosquito biting | 94 (12.62) | 651 (87.38) | |||||

| P5 | I properly cover water containers used for water storage | 399 (53.56) | 346 (46.44) | |||||

| P6 | I keep the water-holding containers (tires, plastic bottles, parts of automobiles, cracked pots, plant pots) clear and drain the extra water | 301 (40.40) | 444 (59.60) | |||||

| P7 | I scrub and clean the inner sides of the containers | 273 (36.64) | 472 (63.36) | |||||

| P8 | I check for the presence of Aedes eggs and/or larvae inside or outside the house | 173 (23.22) | 572 (76.78) | |||||

| P9 | I visit hospital for test and treatment when I see symptoms of Dengue | 424 (56.91) | 321 (43.09) | |||||

| P10 | I follow this disease reduction practices even in the Coronavirus pandemic | 499 (66.98) | 246 (33.02) | |||||

Knowledge, attitude, and practices towards dengue fever (Dhaka, Bangladesh. 2021).

SA, strongly agree; A, Agree; N, Neutral; DA, Disagree and SDA, strongly disagree.

Overall, 50% of respondents replied to appropriate answers to questions regarding the deadly effects of DF, common symptoms of DF, and the infectious nature of DF. In addition, around half of them recognized that the female Aedes mosquito transmits the dengue virus and has a striped body. However, many respondents were unaware that this disease might be asymptomatic (a person could have it without or with mild symptoms), that a previously infected person could have DF again, which could be more severe, and that the virus could be passed to a fetus.

Attitude Regarding Dengue Fever

Table 2 reveals that around 55% of respondents did not agree or were neutral on whether or not they were obligated to guarantee that there are no Aedes eggs or larvae near their dwellings. In addition, many respondents (52%) disagreed or were neutral about the weekly elimination of Aedes mosquito breeding areas. However, almost 50% of respondents agreed they should continue eliminating mosquito breeding areas even during the off-season. Furthermore, 51% stated that chemical fogging alone is insufficient to prevent dengue transmission; authorities must also eliminate potential breeding sites. Less than half (38%) agreed to participate in public action for dengue control or eradication of mosquito breeding places.

Overall, individuals agreed that their families, adjacent communities, and the appropriate authorities are responsible for eliminating potential Aedes mosquito breeding places and guaranteeing the absence of Aedes mosquito eggs and larvae in their immediate environment. They agreed that even if the outbreak is not evident, these activities should be regularly monitored and maintained. Some people thought they were obligated to participate in public DF control programs. Even throughout the COVID-19 outbreak, they were concerned for DF.

Practices Regarding Dengue Fever

Table 2 demonstrates that only 4% of participants contact the municipality for fogging. Approximately 82% of respondents reported utilizing mosquito control or removal techniques. We have also asked about the tools used to protect from mosquito bites for further investigation. Many of them used bed nets (55%) and mosquito coils (44%). They did not, however, cover the water storage containers (46%) or clean them (60%). They go to a hospital for DF testing and treatment (57%). Few of them (23%) monitor the presence of Aedes eggs and/or larvae within and around their dwellings. Even during the pandemic, around 67% adhered to DF precautions.

Overall, the vast majority of participants (>70%) lacked necessary practices, such as engaging with local authorities for fogging, taking additional measures (wearing appropriate clothes, etc.) for DF, and monitoring potential Aedes mosquito breeding places.

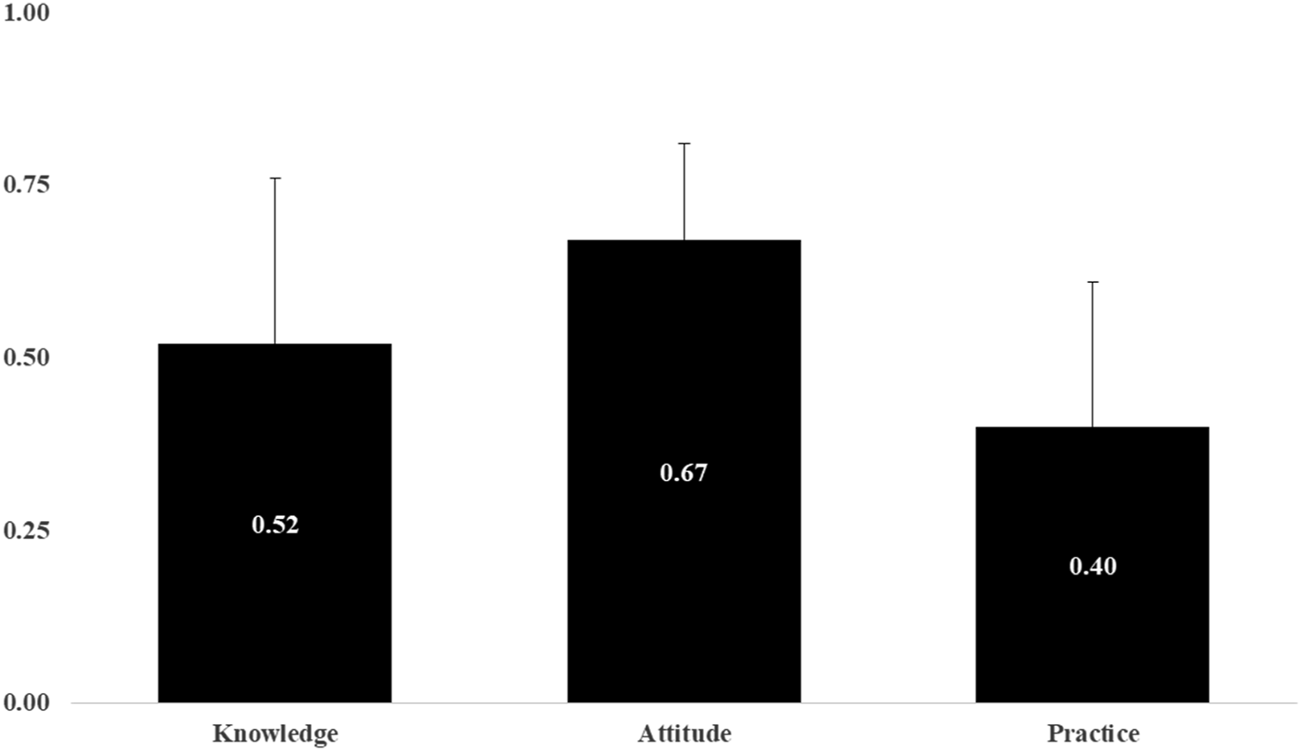

Correlation in KAP Domain

There were found to be positive correlations in the KAP domain (Table 3). Knowledge, attitude, and practices correlate significantly (p < 0.001). Figure 2 shows the mean and standard deviation of overall knowledge, attitude, and practices. 60% of the study group had inadequate preventative measures (0.60 on a scale of 0–1) and knowledge (around 48%) about DF, as shown in Figure 2.

TABLE 3

| Association | r-valuea | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge and Attitude | 0.279 | <0.001 |

| Knowledge and Practice | 0.357 | <0.001 |

| Attitude and Practice | 0.369 | <0.001 |

Association in KAP domain (Dhaka, Bangladesh. 2021).

r-value = correlation coefficient.

FIGURE 2

Mean and standard deviation in knowledge, attitude, and practice section (Dhaka, Bangladesh. 2021).

Determinants of Knowledge

Table 4 presents the findings of the multiple regression analysis. Significant determinants of DF knowledge were marital status, occupation, and information delivery method. The knowledge of married participants is lower than that of unmarried (B = 0.06, 95% CI: 0.01; 0.10) and other (separated, divorced, etc.) (B = 0.12, 95% CI: 0.07; 0.18) individuals. However, working-class people were more knowledgeable than the jobless (B = −0.07, 95% CI: −0.11; −0.04). Respondents who follow people as their source of information demonstrate less knowledge (B = −0.10, 95% CI: −0.14; −0.07) than those who follow electronic media. Social media followers demonstrate greater knowledge (B = 0.16, 95% CI: 0.10; 0.21) than those who follow electronic media for DF information.

TABLE 4

| Characteristics | Model I knowledge | Model II attitude | Model III practice | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ba (95% CIb) | p-value | Ba (95% CIb) | p-value | Ba (95% CIb) | p-value | |

| 1. Age (year) | ||||||

| 18–25 | ||||||

| 26–35 | 0.00 (−0.04; 0.04) | 0.885 | 0.00 (−0.02; 0.71) | 0.656 | 0.04 (−0.00; 0.08) | 0.077 |

| 36–45 | −0.00 (−0.05; 0.05) | 0.985 | −0.00 (−0.04; 0.03) | 0.692 | −0.00 (−0.05; 0.05) | 0.986 |

| More than 45 | −0.01 (−0.0 8; 0.05) | 0.657 | 0.02 (−0.02; 0.06) | 0.388 | 0.02 (−0.0 4; 0.08) | 0.506 |

| 2. Gender | ||||||

| Female | ||||||

| Male | −0.06 (−0.10; −0.03) | 0.000*** | ||||

| 3. Marital status | ||||||

| Married | ||||||

| Unmarried | 0.06 (0.01; 0.10) | 0.023* | 0.02 (−0.01; 0.05) | 0.259 | 0.05 (0.00; 0.10) | 0.029* |

| Other (Separated, Divorced) | 0.12 (0.07; 0.18) | 0.000*** | 0.04 (0.01; 0.07) | 0.020* | 0.08 (0.03; 0.13) | 0.001** |

| 4. Living with family | ||||||

| Yes | ||||||

| No | 0.02 (−0.03; 0.06) | 0.442 | ||||

| 5. Education | ||||||

| ≥ Primary level | ||||||

| No education | 0.67 (−0.01; 0.05) | 0.252 | −0.04 (−0.06; −0.02) | 0.000*** | −0.05 (−0.08; −0.02) | 0.002** |

| 6. Occupation | ||||||

| Worker | ||||||

| No work | −0.07 (−0.11; −0.04) | 0.000*** | ||||

| 7. Media used for dengue fever information | ||||||

| Electronic media (Television, Radio) | ||||||

| Social media | 0.16 (0.10; 0.21) | 0.000*** | 0.01 (−0.02; 0.04) | 0.580 | 0.02 (−0.03; 0.07) | 0.413 |

| People (community, family members) | −0.10 (−0.14; −0.07) | 0.000*** | −0.02 (−0.04; −0.00) | 0.040* | −0.06 (−0.09; −0.03) | 0.000*** |

| Others | 0.13 (0.03; 0.22) | 0.009** | 0.02 (−0.04; 0.08) | 0.601 | −0.03 (−0.12; 0.06) | 0.547 |

| c R2 = 0.20 | c R2 = 0.05 | c R2 = 0.10 | ||||

Predictors of knowledge, attitude, and practices regarding dengue fever (Dhaka, Bangladesh. 2021).

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

B, beta coefficient.

CI, confidence interval.

R2, the coefficient of determination.

Determinants of Attitude

Marital status, level of education, and forms of media for DF information were significant predictors of attitude (Table 4). Married, uneducated (B = 0.67, 95% CI: −0.01; 0.05), and those who followed people (B = −0.10, 95% CI: −0.14; −0.07) as their DF information source had a poorer attitude than those who were separated (B = 0.04, 95% CI: 0.01; 0.07), had a minimal education level, or followed electronic media, respectively.

Determinants of Practices

Gender, marital status, education, and media types were identified as significant determinants of practices against DF (Table 4). Male (B = −0.06, 95% CI: −0.10; −0.03), those who were married, those who lacked formal education (B = −0.05, 95% CI: −0.08; −0.02), and those who relied on people (B = −0.10, 95% CI: −0.14; −0.07) only as a source of DF data were found to engage in poor practices than female, unmarried (B = 0.05, 95% CI: 0.00; 0.10), other (Separated, Divorced) (B = 0.08, 95% CI: 0.03; 0.13), who had minimal education, and individuals who relied on electronic media for DF information.

Discussion

According to our knowledge, this is the first study to apply the KAP model to examine DF responses among slum dwellers of Dhaka, Bangladesh, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to socioeconomic deprivation, individuals may be uneducated and unaware of DF [33, 48]. However, the overall attitude exhibited by the studied population was better than knowledge and practices. It should be noted that slum dwellers lacked DF precautions in the previous study [48]. This study was conducted when COVID-19 became a major safety concern. Numerous slum dwellers may be suffering from and fearful of contracting an infectious disease such as DF. Many of them were concerned about the DF outbreak control efforts. Nonetheless, they contemplated keeping their DF preventive efforts throughout the crisis. Due to the fact that this study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is essential to note that respondents may have had difficulty identifying the fever symptom, which is also characteristic of COVID-19. The circumstance as a whole may impact DF perception. During the pandemic, one web-based study in Dhaka indicated safety concerns over the DF [6].

KAP Status Regarding Dengue Fever

According to the present study’s findings, slum dwellers lack fundamental DF knowledge. Many did not know that dengue is an infectious disease and its common symptoms. Dengue is an infectious disease caused by any of the four related dengue viruses, and it is spread to people through the bite of an infected Aedes species mosquito [49–51]. Symptoms of dengue typically include a high fever, headache, joint and muscle pains, vomiting, and a skin rash; in severe cases, it can lead to serious bleeding, shock, and death [52]. In the case of our previous web-based studies conducted among the general population and university students, we found that many respondents did not know the infectious behavior of the dengue virus [6, 20]. However, slum dwellers have a lower comprehension level than those with greater access to authentic information. Similarly, our study revealed that many slum dwellers were unaware of the asymptomatic characteristics of DF and that DF can be severe in recurrent infections. Most dengue infections are asymptomatic cases, which cause difficulty in disease control and are essential in dengue surveillance [49]. A second infection with other dengue virus serotypes can be more severe and fatal than the initial infection. In this scenario, dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome frequently exhibit more severe symptoms, including fever, thrombocytopenia, hemorrhagic signs, and hypovolemia [52]. The existence of cross-reactive antibodies against distinct dengue virus serotypes has been shown to predispose individuals to more severe disease [53]. It leads to the progression of dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome [54]. These non-neutralizing antibodies can be acquired from a prior infection, passive maternal immunity, or immunization [55]. Our results showed that few individuals correctly identified the risk of dengue virus transmission from pregnant mothers to their fetuses. Bangladesh and Malaysia’s general populations also showed a lack of knowledge regarding the risk of dengue virus transmission during pregnancy [6, 21]. Prior studies have documented this risk [21, 56, 57]. Antibodies against a certain dengue virus serotype might pass the placenta and enter the bloodstream of fetuses, causing a harmful immune response against other serotypes after birth [55]. Children with passive immunity from their mothers are more likely to develop dengue hemorrhagic fever during their initial dengue infection [58, 59]. In addition, many participants failed to correctly identify the breeding locations for Aedes mosquitoes, resulting in an increased risk of severe DF, as reported by a previous study [6, 60]. Identifying and eradicating dengue mosquito breeding grounds is essential for reducing the disease’s spread.

Numerous members of the study population agreed on effective efforts to eliminate mosquitoes. However, many did not monitor mosquito eggs and larvae at home and in the environment. Inadequate mosquito breeding prevention techniques have shown a knowledge gap. Additionally, it conforms to research conducted in Bangladesh and Vietnam [6, 38]. Aedes mosquitoes breed in water-filled containers such as tires, barrels, plastic drums, jerry cans, and abandoned containers [61, 62]. A study conducted in Malaysia found that many people believed that eliminating dengue mosquito larvae is a complete waste of time [63]. However, these breeding grounds should be identified and eliminated, particularly in tropical and subtropical locations where Aedes mosquitoes are prevalent [61]. Moreover, these mosquito breeding sites’ monitoring activities should be maintained even in the off-season when DF is not frequent. Even during the off-season, it is typically advised to continue destroying mosquito breeding sites to avoid the growth of mosquito populations and reduce the risk of disease transmission [64]. Half of our study population also agreed with it. The participants in the survey agreed that fogging alone is insufficient to manage the dengue outbreak; instead, it requires a holistic approach in which families, communities, and the government unite to reduce mosquito breeding sites. This result is consistent with prior research [6, 65]. However, this result contradicts previous research [21, 66], where most communities agreed on chemical fogging and eliminating mosquito breeding areas instead. Chemical fogging is one method for controlling the DF outbreak, with advantages and disadvantages [67]. While chemical fogging efficiently reduces mosquitoes and prevents the spread of diseases transmitted by mosquitoes [68], it can also lead to the development of insecticide resistance, adverse effects on non-target organisms, and potential health risks to humans [69, 70]. In order to effectively manage mosquitoes, it is necessary to use chemical fogging sparingly and in conjunction with other control methods. Few respondents sought fog from the authority, and the majority did not monitor mosquito breeding places. It demonstrated the gap between this group and the authority, highlighted in a recent COVID-19 survey of Bangladeshis [9]. In addition, individuals may feel that authorities will fog the area when necessary. Regular monitoring of mosquito breeding locations is essential, along with aggressive DF control actions [21]. Our research also found that many slum dwellers are unwilling to participate in mosquito control efforts. A study in the slums of Delhi, India, revealed minimal involvement in the local municipality’s mosquito control and health promotion initiatives [71]. They have suggested that participation might result in a favorable shift in behavior. Numerous individuals did not clean the water storage to eliminate mosquito breeding grounds. Dengue-carrying Aedes mosquitoes lay their eggs on the walls of water-filled containers in and near homes and terraces [72]. Female mosquitoes may lay eggs up to five times throughout their lifespan, and the eggs can remain viable for months [73]. Identifying and eliminating standing water in and around dwellings is necessary to avoid Aedes mosquito breeding [74, 75]. We observed that Dhaka city slum dwellers utilized bed nets to prevent mosquito bites during our further investigation. The WHO recommends maintaining mosquito nets during the day since dengue mosquitoes typically bite during the day [76]. In addition, the study suggests that those who use bed nets to avoid other mosquito-borne diseases may be more cognizant of the danger posed by mosquito bites and may be more vigilant in preventing mosquito bites during the day [27]. Another study found that majority of slum dwellers in Kolkata, India utilized mosquito coils or repellent as a preventative method [77]. For efficient Aedes mosquito management, it is necessary to take a multifaceted strategy. A combination of these approaches can aid in reducing mosquitoes and halting the spread of diseases they transmit.

KAP Determinants

Mortality from dengue can be minimized with early identification based on patient data [39]. Assume that the health workers and organizations working for DF control have access to expedited information, such as the socio-demographic status of individuals as a factor correlating with DF responses. They can intervene and aid in the DF’s effective control attempt in such a circumstance. We observed that a level of education and different media are significant factors in slum dwellers’ DF behavior. In addition, a study conducted in the slums of Kolkata, India, revealed that education significantly influences one’s knowledge and practice [77]. According to studies, improved socioeconomic conditions may contribute to successful DF behavior, including practices [6, 21, 78]. Those without education who follow solely individuals (as opposed to social and electronic media) have weak KAP. Interestingly, married individuals have a lower KAP than single individuals. This result contradicts the prior research done in Malaysia [21]. Although marital status may influence dengue fever knowledge, attitude, and practices, the evidence is limited, and other demographic and socioeconomic factors are likely to have a more substantial effect. Therefore, more study is required to investigate the association between marital status and dengue fever knowledge, attitude, and practices. Without effective DF control initiatives, DF can proliferate in slum areas. Together with national and local authorities, they should organize a committee to perform routine DF surveillance.

Recommendations

This survey included Dhaka city slum dwellers primarily. This group has been identified as one of the most susceptible to any threat [33, 79]. Therefore, efforts must be made to prepare this population for a DF outbreak. The authority’s plan should ensure proper transmission of knowledge, a positive attitude, and preventative measures regarding DF. Governments must also establish campaigns, social mobilization, and communication to educate and train these dwellers on DF management. Television, radio, and social media may offer educational initiatives, such as short films, case studies, and early warnings on DF outbreak control strategies. A survey in Delhi, India’s urban slums, revealed that television is the primary source of information for DF [80]. In Bangladesh, social media has become an increasingly significant source of news and information [15]. Nonetheless, literacy and cognitive comprehension must be considered while creating and executing these approaches [27]. Through these platforms, the health and disaster management authorities might also include information linked to dengue outbreaks before and after their occurrence. The government must adequately equip its personnel and essential stakeholders to tackle this fatal disease [81]. One study also recommended extensive engagement between researchers, companies, and communities in order to develop efficient dengue management techniques [82]. A study done in the slums of Islamabad, Pakistan, suggests adopting a positive deviance (PD) strategy to enhance the KAP regarding DF [83]. This strategy has enormous potential as a tool for behavior modification and community participation in dengue prevention and management [83]. A small-scale review of malaria research done in Cambodia provided overwhelmingly favorable comments on the PD approach’s efficacy in engaging people [84]. Authorities in Bangladesh may also consider similar method for slum dwellers regarding DF control. A project called “Project Mosblock” has been launched to tackle the ever-growing mosquito-borne disease by giving slum dwellers in Dhaka with a specific sort of curtain [85]. In a pilot study of the initiative, zebra-patterned curtains were supplied to dwellers of one of Bangladesh’s largest slums, the Korail Slum in the city. Officials with the initiative claim that zebra stripes repel bloodsucking insects such as mosquitoes by rendering them incapable of landing on the animal’s skin. Officials of the project thought that the endeavor would curb the mosquito-borne disease outbreak in the slums of the city.

This study’s findings can be applied to other dengue-risk settings, especially informal settlements. Authorities and communities throughout the world are alarmed by the outbreak. Research determined the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on India’s vector control program [86]. The increased dengue risk caused by the lockdown has been addressed in the previous study [86]. Consequently, assessing the KAP level for DF during the pandemic is imperative. Our KAP model suggests that the increasing knowledge of individuals may result in behavioral changes, such as improved attitudes and practices about DF. In addition, the associated predictors of KAP have been identified. This knowledge might be incorporated into other DF-affected nations’ dengue outbreak control plans, particularly for vulnerable people such as slum dwellers.

Limitations

The limitations of the current study should be considered when interpreting the results. First, non-probability sampling approaches were utilized during the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, this survey may have some inherent biases. Respondents could consider socially acceptable responses, even with the anonymous survey format. So, it might be for the face-to-face interview. Many of the population under study are uneducated and may lack access to certain DF response facilities. Regarding these, respondents exhibited inadequate knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Second, it is considered just the capital city of Bangladesh most severely hit by DF; hence the research population may not represent Bangladesh’s vast population. This exploratory study might offer the Bangladeshi government crucial information despite its limitations. In addition, this study’s insights can aid other impacted areas in integrating DF control efforts, particularly during pandemics.

Conclusion

During this study, all countries were concerned with pandemic control. Consequently, it may be difficult to concentrate on DF control activities. Nonetheless, the risk of DF can be reduced even during a pandemic by adhering to community standards and adopting traditional wisdom, national legislation, and international standards with the proper authority. Our findings indicate that slum dwellers lacked the knowledge and practices necessary to reduce DF risk. In addition, we may assume that effective dissemination of knowledge, community stimulation toward a positive attitude, and frequent monitoring of preventative activities will be required to control DF outbreak. Increasing the dwellers’ quality of life may also help manage the DF. Therefore, a multidisciplinary strategy is required to influence the behavior of dwellers. It is possible by unifying stakeholders behind a common objective. In order to reduce vector breeding grounds without harming the environment, coupling vector control strategies will rely heavily on individual and community efforts.

Statements

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Research Ethics Committee, Bangladesh University of Professionals. Consent was obtained from respondents, who remained anonymous.

Author contributions

MR, KT, and TR: performed the analysis and drafted the manuscript. MR, KT, and TR: designed and supervised the analysis, co-drafted the manuscript. MR, KT, TR, MI, MAR, MS, MAQ, N-U-IB, IS, AS, MH, FF, FT, FR, EA, and AM: data collection, conceived of the study, and reviewed.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely appreciate the experts’ thoughtful feedback on the work. The authors also thank the university students and research participants for their invaluable assistance.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

1.

Islam S Khatun H . Awareness and Preparedness of Disasters in Bangladesh-A Study of Dhaka City Dwellers. Soc Sci Rev (2015) Part-D 32.1:57–70.

2.

Rigaud KK de Sherbinin A Jones B Bergmann J Clement V Ober K et al Groundswell. Washington, DC: World Bank (2018). Available from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/29461 (Cited Apr 21, 2020).

3.

Hossain MS Siddiqee MH Siddiqi UR Raheem E Akter R Hu W . Dengue in a Crowded Megacity: Lessons Learnt from 2019 Outbreak in Dhaka, Bangladesh. PLOS Negl Trop Dis (2020) 14(8):e0008349. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008349)

4.

Md Mostafizur Rahman P Tanbir Amin BSS Saima Bintay Sultan BSS Bithi MI Farzana Rahman P Md Moshiur Rahman P . Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Among Public university Students in Bangladesh during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Emerg Manage (2021) 19(9):99–107. 10.5055/jem.0616

5.

Rahman MM Khan SJ Sakib MS Chakma S Procheta NF Mamun ZA et al Assessing the Psychological Condition Among General People of Bangladesh during COVID-19 Pandemic. J Hum Behav Soc Environ (2020) 19:1–15. 10.1080/10911359.2020.1848688

6.

Rahman MM Islam ARMT Khan SJ Tanni KN Roy T Islam MR et al Dengue Fever Responses in Dhaka City, Bangladesh: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int J Public Health (2022) 67:1604809. 10.3389/ijph.2022.1604809

7.

Rahman MM Jhinuk JM Nabila NH Yeasmin MTM Shobuj IA Sayma TH et al Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices towards COVID-19 during the Rapid Rise Period: A Cross-Sectional Survey Among Public University Students of Bangladesh. SciMedicine J (2021) 3(2):116–28. 10.28991/SciMedJ-2021-0302-4

8.

Rahman MM Khan SJ Sakib MS Halim MA Rahman MM Asikunnaby et al COVID-19 Responses Among university Students of Bangladesh: Assessment of Status and Individual View toward COVID-19. J Hum Behav Soc Environ (2021) 31:512–31. 10.1080/10911359.2020.1822978

9.

Rahman MM Khan SJ Sakib MS Halim MA Rahman F Rahman MM et al COVID-19 Responses Among General People of Bangladesh: Status and Individual View toward COVID-19 during Lockdown Period. Cogent Psychol (2021) 8(1):1860186. 10.1080/23311908.2020.1860186

10.

Bashar K Mahmud S Asaduzzaman Tusty EA Zaman AB . Knowledge and Beliefs of the City Dwellers Regarding Dengue Transmission and Their Relationship with Prevention Practices in Dhaka City, Bangladesh. Public Health Pract (2020) 1:100051. 10.1016/j.puhip.2020.100051

11.

Bhatt S Gething PW Brady OJ Messina JP Farlow AW Moyes CL et al The Global Distribution and burden of Dengue. Nature (2013) 496(7446):504–7. 10.1038/nature12060

12.

Raheel U Faheem M Riaz MN Kanwal N Javed F Zaidi N et al Dengue Fever in the Indian Subcontinent: an Overview. The J Infect Developing Countries (2011) 5(04):239–47. 10.3855/jidc.1017

13.

Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS). Daily Dengue Status Report (2020). Available from: https://dghs.gov.bd/index.php/bd/home/5200-daily-dengue-status-report (Cited Dec 16, 2020).

14.

Mutsuddy P Tahmina Jhora S Shamsuzzaman AKM Kaisar SMG Khan MNA . Dengue Situation in Bangladesh: An Epidemiological Shift in Terms of Morbidity and Mortality. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol (2019) 2019:e3516284. 10.1155/2019/3516284

15.

Rahman MS Karamehic-Muratovic A Baghbanzadeh M Amrin M Zafar S Rahman NN et al Climate Change and Dengue Fever Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices in Bangladesh: a Social media–based Cross-Sectional Survey. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg (2020) 115:85–93. 10.1093/trstmh/traa093

16.

Dhar-Chowdhury P Paul KK Haque CE Hossain S Lindsay LR Dibernardo A et al Dengue Seroprevalence, Seroconversion and Risk Factors in Dhaka, Bangladesh. PLOS Negl Trop Dis (2017) 11(3):e0005475. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005475

17.

Mamun MA Misti JM Griffiths MD Gozal D . The Dengue Epidemic in Bangladesh: Risk Factors and Actionable Items. Lancet (2019) 394(10215):2149–50. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32524-3

18.

Dhaka Tribune. Latest News Update from Dengue in Bangladesh, World (2021). Available from: https://www.dhakatribune.com/tags/dengue (Cited Dec 21, 2020).

19.

Coudeville L Baurin N Shepard DS . The Potential Impact of Dengue Vaccination with, and without, Pre-vaccination Screening. Vaccine (2020) 38(6):1363–9. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.12.012

20.

Rahman MM Khan SJ Tanni KN Roy T Chisty MA Islam MR et al Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices towards Dengue Fever Among University Students of Dhaka City, Bangladesh. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2022) 19(7):4023. 10.3390/ijerph19074023

21.

Selvarajoo S Liew JWK Tan W Lim XY Refai WF Zaki RA et al Knowledge, Attitude and Practice on Dengue Prevention and Dengue Seroprevalence in a Dengue Hotspot in Malaysia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Sci Rep (2020) 10(1):9534. 10.1038/s41598-020-66212-5

22.

Rahman MM Nabila IA Sakib MS Silvia NJ Galib MA Shobuj IA et al Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices towards Lightning in Bangladesh. Sustainability (2022) 14(1):448. 10.3390/su14010448

23.

Rahman MM Nabila IA Sakib MS Silvia NJ Galib MA Shobuj IA et al Status and Individual View toward Lightning Among University Students of Bangladesh. Sustainability (2022) 14(15):9314. 10.3390/su14159314

24.

Launiala A . How Much Can a KAP Survey Tell Us about People’s Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices? Some Observations from Medical Anthropology Research on Malaria in Pregnancy in Malawi. Anthropol Matters (2009) 11(1), 1–13. 10.22582/am.v11i1.31

25.

WHO. Health Education: Theoretical Concepts, Effective Strategies and Core Competencies: A Foundation Document to Guide Capacity Development of Health Educators (2012). Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/119953 (Cited May 25, 2021).

26.

Dauda Goni M Hasan H Naing NN Wan-Arfah N Zeiny Deris Z Nor Arifin W et al Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practice towards Prevention of Respiratory Tract Infections Among Hajj and Umrah Pilgrims from Malaysia in 2018. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2019) 16(22):4569. 10.3390/ijerph16224569

27.

Abir T Ekwudu O Kalimullah NA Yazdani DMNA Mamun AA Basak P et al Dengue in Dhaka, Bangladesh: Hospital-Based Cross-Sectional KAP Assessment at Dhaka North and Dhaka South City Corporation Area. PLOS ONE (2021) 16(3):e0249135. 10.1371/journal.pone.0249135.

28.

Correspondent S . Study Finds Highest Level of Aedes Larvae at Hospitals, Transport Hubs, Slums in Dhaka. bdnews24.com (2019). Available from: https://bdnews24.com/bangladesh/study-finds-highest-level-of-aedes-larvae-at-hospitals-transport-hubs-slums-in-dhaka (Cited Sep 1, 2022).

29.

The Financial Express. Highest Level of Aedes Larvae Found at Transport Hubs, Slums in Dhaka. The Financial Express (2019). Available from: https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/national/country/highest-level-of-aedes-larvae-found-at-transport-hubs-slums-in-dhaka-1565605853 (Cited Sep 1, 2022).

30.

Neiderud CJ . How Urbanization Affects the Epidemiology of Emerging Infectious Diseases. Infect Ecol Epidemiol (2015) 5(1):27060. 10.3402/iee.v5.27060

31.

WHO. Our Cities, Our Health, Our Future: Acting on Social Determinants for Health Equity in Urban Settings. Report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health from the Knowledge Network on Urban Settings. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2008).

32.

WHO. Hidden Cities: Unmasking and Overcoming Health Inequities in Urban Settings. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2010).

33.

UNICEF Bangladesh. Analysis of the Situation of Children and Women in Bangladesh 2015. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Social Policy, Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation Section, United Nations Children’s Fund (2015). p. 210.

34.

Angeles G Lance P Barden-O’Fallon J Islam N Mahbub A Nazem NI . The 2005 Census and Mapping of Slums in Bangladesh: Design, Select Results and Application. Int J Health Geogr (2009) 8(1):32. 10.1186/1476-072X-8-32

35.

Hossain MI Wagatsuma Y Chowdhury MA Ahmed TU Uddin A Sohel SMN et al Analysis of Some Socio-Demographic Factors Related to DF/DHF Outbreak in Dhaka City. Dengue Bull (2000) 24:34–41.

36.

Sharmin S Glass K Viennet E Harley D . Interaction of Mean Temperature and Daily Fluctuation Influences Dengue Incidence in Dhaka, Bangladesh. PLOS Negl Trop Dis (2015) 9(7):e0003901. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003901

37.

Baker JL . Bangladesh - Dhaka: Improving Living Conditions for the Urban Poor. Washington, D.C.: World Bank (2007). Available from: https://fid4sa-repository.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/3567/ (Cited Apr 14, 2022).

38.

Nguyen HV Hoang CL Tran TT Truong NT Nguyen SH Do HP et al Knowledge, Attitude and Practice about Dengue Fever Among Patients Experiencing the 2017 Outbreak in Vietnam. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2019) 12:976. 10.3390/ijerph16060976

39.

World Health Organization. Global Strategy for Dengue Prevention and Control, 2012-2020. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2012). Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75303/1/9789241504034_eng.pdf (Cited Dec 16, 2020).

40.

Harapan H Rajamoorthy Y Anwar S Bustamam A Radiansyah A Angraini P et al Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Regarding Dengue Virus Infection Among Inhabitants of Aceh, Indonesia: a Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Infect Dis (2018) 18:96. 10.1186/s12879-018-3006-z

41.

Mahendraker AG Kovattu AB Kumar S . Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice toward Dengue Fever Among Residents in Raichur. Indian J Health Sci Biomed Res (Kleu) (2020) 13(2):112. 10.4103/kleuhsj.kleuhsj_28_20

42.

Ursachi G Horodnic IA Zait A . How Reliable Are Measurement Scales? External Factors with Indirect Influence on Reliability Estimators. Proced Econ Finance (2015) 20:679–86. 10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00123-9

43.

Stratton SJ . Population Research: Convenience Sampling Strategies. Prehosp Disaster Med (2021) 36(4):373–4. 10.1017/S1049023X21000649

44.

Rahman MM Khan SJ Tanni KN Sakib MS Quader MA Shobuj IA et al Holistic Individual Fire Preparedness in Informal Settlements, Bangladesh. Fire Technol (2022):1–28. 10.1007/s10694-022-01340-0

45.

Yamane T . Statistics an Introductory Analysis. 2nd ed. 2nd ed.New York: Harper & Row (1967). p. 919.

46.

RStudio. Open Source & Professional Software for Data Science Teams (2021). Available from: https://rstudio.com/ (Cited Jan 15, 2021).

47.

Python.org. Welcome to Python.Org (2021). Available from: https://www.python.org/ (Cited Jan 15, 2021).

48.

Ahmed T Bashar K Rahman GM Shamsuzzaman M Samajpati S Sultana S et al Some Socio-Demographic Factors Related to Dengue Outbreak in Dhaka City, Bangladesh. Bangladesh J Zoolog (2007) 35:213–22.

49.

Chatchen S Sabchareon A Sirivichayakul C . Serodiagnosis of Asymptomatic Dengue Infection. Asian Pac J Trop Med (2017) 10(1):11–4. 10.1016/j.apjtm.2016.12.002

50.

Guzmán MG Kouri G . Dengue: an Update. Lancet Infect Dis (2002) 2(1):33–42. 10.1016/s1473-3099(01)00171-2

51.

Halstead SB . Dengue, 5. Singapore: World Scientific (2008).

52.

Rigau-Pérez JG Clark GG Gubler DJ Reiter P Sanders EJ Vorndam AV . Dengue and Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever. Lancet (1998) 352(9132):971–7. 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)12483-7

53.

Morens DM Venkateshan CN Halstead SB . Dengue 4 Virus Monoclonal Antibodies Identify Epitopes that Mediate Immune Infection Enhancement of Dengue 2 Viruses. J Gen Virol (1987) 68(1):91–8. 10.1099/0022-1317-68-1-91

54.

Guzman MG Alvarez M Halstead SB . Secondary Infection as a Risk Factor for Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever/dengue Shock Syndrome: an Historical Perspective and Role of Antibody-dependent Enhancement of Infection. Arch Virol (2013) 158(7):1445–59. 10.1007/s00705-013-1645-3

55.

Ulrich H Pillat MM Tárnok A . Dengue Fever, COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2), and Antibody-dependent Enhancement (ADE): A Perspective. Cytometry A (2020) 97(7):662–7. 10.1002/cyto.a.24047

56.

Mohamed Ismail NA Wan Abd Rahim WER Salleh SA Neoh HM Jamal R Jamil MA . Seropositivity of Dengue Antibodies during Pregnancy. Sci World J (2014) 2014:436975. 10.1155/2014/436975

57.

Tan PC Soe MZ Lay KS Wang SM Sekaran SD Omar SZ . Dengue Infection and Miscarriage: A Prospective Case Control Study. PLOS Negl Trop Dis (2012) 6(5):e1637. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001637

58.

Halstead SB Lan NT Myint TT Shwe TN Nisalak A Kalyanarooj S et al Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever in Infants: Research Opportunities Ignored. Emerging Infect Dis(2002) 8(12):1474–1479. 10.3201/eid0812.020170

59.

Simmons CP Chau TNB Thuy TT Tuan NM Hoang DM Thien NT et al Maternal Antibody and Viral Factors in the Pathogenesis of Dengue Virus in Infants. J Infect Dis (2007) 196(3):416–24. 10.1086/519170

60.

Wang TT Sewatanon J Memoli MJ Wrammert J Bournazos S Bhaumik SK et al IgG Antibodies to Dengue Enhanced for FcγRIIIA Binding Determine Disease Severity. Science (2017) 355(6323):395–8. 10.1126/science.aai8128(

61.

Ferdousi F Yoshimatsu S Ma E Sohel N Wagatsuma Y . Identification of Essential Containers for Aedes Larval Breeding to Control Dengue in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Trop Med Health (2015) 43(4):253–64. 10.2149/tmh.2015-16

62.

Waldetensai A Gemechu F Kinfe E Amare H Hagos S Teshome D et al Aedes Mosquito Responses to Control Interventions against the Chikungunya Outbreak of Dire Dawa, Eastern Ethiopia. Int J Trop Insect Sci (2021) 41(4):2511–20. 10.1007/s42690-021-00430-w

63.

Al-Dubai SAR Ganasegeran K Alwan MR Alshagga MA Saif-Ali R . Factors Affecting Dengue Fever Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Among Selected Urban, Semi-urban and Rural Communities in Malaysia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health (2013) 44(1):37–49.

64.

Leach CB Hoeting JA Pepin KM Eiras AE Hooten MB Webb CT . Linking Mosquito Surveillance to Dengue Fever through Bayesian Mechanistic Modeling. PLOS Negl Trop Dis (2020) 14(11):e0008868. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008868

65.

Kamel MNAM Gnanakkan BD Fauzi FZ Hanafi MI Selvarajah G Jabar SA et al The KAP Study on Dengue Among Community in Taman Salak Baiduri, Sepang. Selangor Age (2017) 18(19):2.

66.

Zaki R Roffeei SN Hii YL Yahya A Appannan M Said MA et al Public Perception and Attitude towards Dengue Prevention Activity and Response to Dengue Early Warning in Malaysia. PloS one (2019) 14(2):e0212497. 10.1371/journal.pone.0212497

67.

Zahir A Ullah A Shah M Mussawar A . Community Participation, Dengue Fever Prevention and Control Practices in Swat, Pakistan. Int J MCH AIDS (2016) 5(1):39–45. 10.21106/ijma.68

68.

Alto BW Lounibos LP Mores CN Reiskind MH . Larval Competition Alters Susceptibility of Adult Aedes Mosquitoes to Dengue Infection. Proc R Soc B: Biol Sci (2007) 275(1633):463–71. 10.1098/rspb.2007.1497

69.

Abeyasuriya KGTN Nugapola NWNP Perera MDB Karunaratne WAIP Karunaratne SHPP . Effect of Dengue Mosquito Control Insecticide thermal Fogging on Non-target Insects. Int J Trop Insect Sci (2017) 37(1):11–8. 10.1017/s1742758416000254

70.

Liu N . Insecticide Resistance in Mosquitoes: Impact, Mechanisms, and Research Directions. Annu Rev Entomol (2015) 60(1):537–59. 10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020828

71.

Kusuma YS Goswami AK Babu BV . Dengue Awareness, Preventive Behaviours and Aedes Breeding Opportunities Among Slums and Slum-like Pockets in Delhi, India: a Formative Assessment. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg (2021) 115(6):653–63. 10.1093/trstmh/traa103

72.

Simard F Nchoutpouen E Toto JC Fontenille D . Geographic Distribution and Breeding Site Preference of Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) in Cameroon, Central Africa. J Med Entomol (2005) 42(5):726–31. 10.1093/jmedent/42.5.726

73.

Angel A Angel B Yadav N Narang J Yadav SS Joshi V . Aedes Mosquitoes: The Universal Vector. In: Small Bite, Big Threat. Dubai, UAE: Jenny Stanford Publishing (2020).

74.

Barrera R Navarro JC Domnguez D Gonzalez J . Public Service Deficiencies and Aedes aegypti Breeding Sites in Venezuela. Bull Pan Am Health Organ (1995) 29(3):193–205.

75.

Wong J Stoddard ST Astete H Morrison AC Scott TW . Oviposition Site Selection by the Dengue Vector Aedes aegypti and its Implications for Dengue Control. PLOS Negl Trop Dis (2011) 5(4):e1015. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001015

76.

World Health Organization. Dengue Guidelines, for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control (2009). Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241547871 (Cited Aug 31, 2022).

77.

Podder D Paul B Dasgupta A Bandyopadhyay L Pal A Roy S . Community Perception and Risk Reduction Practices toward Malaria and Dengue: A Mixed-Method Study in Slums of Chetla, Kolkata. Indian J Public Health (2019) 63(3):178–85. 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_321_19

78.

Ghani NA Shohaimi S Hee AKW Chee HY Emmanuel O Alaba Ajibola LS . Comparison of Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Among Communities Living in Hotspot and Non-hotspot Areas of Dengue in Selangor, Malaysia. Trop Med Infect Dis (2019) 4(1):37. 10.3390/tropicalmed4010037

79.

Ahmed I . Factors in Building Resilience in Urban Slums of Dhaka, Bangladesh. Proced Econ Finance (2014) 18:745–53. 10.1016/s2212-5671(14)00998-8

80.

Kohli C Kumar R Meena GS Singh MM Ingle GK . A Study on Knowledge and Preventive Practices about Mosquito Borne Diseases in Delhi. MAMC J Med Sci (2015) 1(1):16. 10.4103/2394-7438.150054

81.

Rahman MS Overgaard HJ Pientong C Mayxay M Ekalaksananan T Aromseree S et al Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices on Climate Change and Dengue in Lao People’s Democratic Republic and Thailand. Environ Res (2021) 193:110509. 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110509

82.

Devine GJ Overgaard HJ Paul RE . Global Vector Control Guidelines – the Need for Co-creation. Trends Parasitol (2019) 35(4):267–70. 10.1016/j.pt.2018.12.003

83.

Shafique M Mukhtar M Areesantichai C Perngparn U . Effectiveness of Positive Deviance, an Asset-Based Behavior Change Approach, to Improve Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Dengue in Low-Income Communities (Slums) of Islamabad, Pakistan: A Mixed-Method Study. Insects (2022) 13(1):71. 10.3390/insects13010071

84.

Shafique M Edwards HM De Beyl CZ Thavrin BK Min M Roca-Feltrer A . Positive Deviance as a Novel Tool in Malaria Control and Elimination: Methodology, Qualitative Assessment and Future Potential. Malar J (2016) 15(1):91. 10.1186/s12936-016-1129-5

85.

Staff T . MosBlock - the Zebra Patterned Mosquito Repellent to Combat Dengue. Branding in Asia Magazine (2022). Available from: https://www.brandinginasia.com/mosblock-the-zebra-patterned-mosquito-repellent-to-combat-dengue/ (Cited Sep 1, 2022).

86.

Daniel Reegan A Rajiv Gandhi M Cruz Asharaja A Devi C Shanthakumar SP . COVID-19 Lockdown: Impact Assessment on Aedes Larval Indices, Breeding Habitats, Effects on Vector Control Programme and Prevention of Dengue Outbreaks. Heliyon (2020) 6(10):e05181. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05181

Summary

Keywords

COVID-19, Bangladesh, slums, dengue, Dhaka city

Citation

Rahman MM, Tanni KN, Roy T, Islam MR, Al Raji Rumi MA, Sadman Sakib M, Abdul Quader M, Bhuiyan N-U-I, Shobuj IA, Sayara Rahman A, Haque MI, Faruk F, Tahsan F, Rahman F, Alam E and Md. Towfiqul Islam AR (2023) Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Towards Dengue Fever Among Slum Dwellers: A Case Study in Dhaka City, Bangladesh. Int J Public Health 68:1605364. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2023.1605364

Received

01 September 2022

Accepted

09 May 2023

Published

22 May 2023

Volume

68 - 2023

Edited by

Jean Tenena Coulibaly, Félix Houphouët-Boigny University, Côte d'Ivoire

Reviewed by

Gilbert Fokou, Swiss Centre for Scientific Research, Côte d'Ivoire

Jean Tenena Coulibaly, Félix Houphouët-Boigny University, Côte d'Ivoire

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Rahman, Tanni, Roy, Islam, Al Raji Rumi, Sadman Sakib, Abdul Quader, Bhuiyan, Shobuj, Sayara Rahman, Haque, Faruk, Tahsan, Rahman, Alam and Md. Towfiqul Islam.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Md. Mostafizur Rahman, mostafizur@bup.edu.bd

This Original Article is part of the IJPH Special Issue “Neglected Tropical Diseases During the COVID-19 Pandemic”

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.