- 1Psychology Program, International University of Sarajevo, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

- 2Public Health Institute of Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Objectives: To conduct qualitative study with different target groups in Bosnia and Herzegovina in order to explore their views on barriers and drivers for COVID-19 vaccination, and to see if and how barriers and drivers vary between urban and rural locations, and different professional roles.

Methods: The theoretical framework underpinning the study is the capability-opportunity-motivation (COM-B) behavior change framework, which has been adapted to monitor vaccine related behavior and attitudes. Data was collected from June to September 2022 through moderated discussions in focus groups. The total of 162 participants participated in 16 focus groups.

Results: Among the key barriers to successful immunization identified across target groups were insufficient knowledge about vaccines, pandemic fatigue, concerns about the rapid development of the vaccine and its effectiveness, lack of confidence in the healthcare system. Some of the main drivers of vaccination against COVID-19 were confidence in science and expert recommendations.

Conclusion: The COVID-19 immunization policy undergoes continuous changes, as do the pandemic prospects; we encourage further research to track the evolution of vaccine related attitudes, inform immunization policy, and create evidence-based interventions.

Introduction

Safe and effective vaccination is a key public health intervention to control the COVID-19 pandemic. It is estimated that COVID-19 vaccinations prevented 14.4 million (95% Crl 13.7–15.9) deaths from COVID-19 across 185 countries and territories in the first year that vaccines were available [1]. Nevertheless, COVID-19 vaccines have posed a unique set of challenges to vaccine acceptance.

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy has been found to differ significantly across countries and among key groups, posing a threat to vaccination campaigns [2]. Negative perceptions of safety, trust in the science behind vaccine development, and vaccine efficacy were the most consistent correlates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, as well as government mistrust, while other factors varied by country and included personal experience with COVID-19 and demographic characteristics [3].

Healthcare workers (HCWs) were a priority group for COVID-19 vaccination worldwide [4, 5]. Moreover, HCWs are considered a reliable source of information and can significantly influence patients’ decisions about vaccination. Therefore, if attitudes regarding COVID-19 vaccination are negative among HCWs, it is likely that such attitudes would be negative among the general public as well [6]. Determinants of vaccination hesitancy among HCWs are mainly related to concerns about the vaccine’s side effects or lack of scientific information about the vaccine [7]. Specific to western Balkan countries, literature indicates that, in general, HCWs moderately believed that COVID-19 vaccines were a beneficial and safe intervention, would successfully reduce disease burden, and that socio-demographic characteristics might not be particularly relevant factors of vaccination intention [8].

According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO), almost 2 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines were administered in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) (population 3.2 million) by the end of January 2022, of which almost 850,000 people were fully vaccinated [9]. It is important to note that the official data likely underestimate COVID-19 vaccination coverage, due to the vaccination of BiH residents in neighboring countries as a result of significant COVID-19 vaccine supply constraints during the first half of 2021, as well as challenges calculating accurate denominators. Authorities in the state procured COVID-19 vaccines that were developed using a variety of different platforms, initially mostly vector-based and inactivated vaccines.

To develop effective recommendations for policies, it is important to understand the drivers and barriers to vaccination [10], especially in key professions such as HCWs and teachers; as well as the lowest-coverage groups, such as people aged 18–24 and the working-age population (e.g., individuals aged 25–65). The first objective of the current study was to explore the views of target groups regarding barriers and drivers for COVID-19 vaccination, as well as on recommending vaccination to patients (for HCWs), organized around four main themes: knowledge and health literacy concerning COVID-19 vaccines and vaccination; attitudes and intentions towards COVID-19 vaccines and vaccination; social support and social norms for COVID-19 vaccines (and recommending vaccination - for HCWs), and; access to COVID-19 vaccination.

The second objective of the study was to analyze the data to see if and how barriers and drivers varied between urban and rural locations, and different professional roles (teachers, medical doctors, nurses).

Methods

Study Design

The study was conducted from June 2022 to September 2022 on the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina, in both entities, in four phases [1]: protocol preparation [2], field work organization [3], data collection, and [4] data analysis. Data was collected through moderated focus group discussions, with focus groups comprised of participants from the same target group. Focus groups were selected as the data collection method because they allow participants to freely exchange opinions, that is, the exchange of opinions can be stimulated by the presence of others. The group discussions lasted between 60 and 90 min on average, and were moderated by a trained researcher. The study was conducted in the local (Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian) language. Interviews were recorded with participants’ permission. The focus groups discussions followed a guide, which contained semi-structured questions, and anonymity was guaranteed to facilitate participant comfort, and willingness to speak openly, that is, to freely share their opinions and give open and honest answers. The protocol and discussion guide were developed by researchers with expertise in qualitative methodology (NBC and SM), and they are based on the WHO Rapid qualitative research to increase COVID-19 vaccination uptake—A research and intervention tool [11]. The theoretical framework underpinning the study and analysis is the Capability-Opportunity-Motivation (COM-B) behaviour change framework, which has been adapted and used to monitor vaccine-related behaviour and attitudes and has also been used for designing a discussion guide [10, 11]. The COM-B framework identifies the interrelated factors of individual (physical and psychological) capability, physical and social opportunities, and motivation as influences on individuals’ vaccination related behaviors, providing a holistic approach to exploring barriers and opportunities associated with individual health behaviors.

Data Collection and Analysis

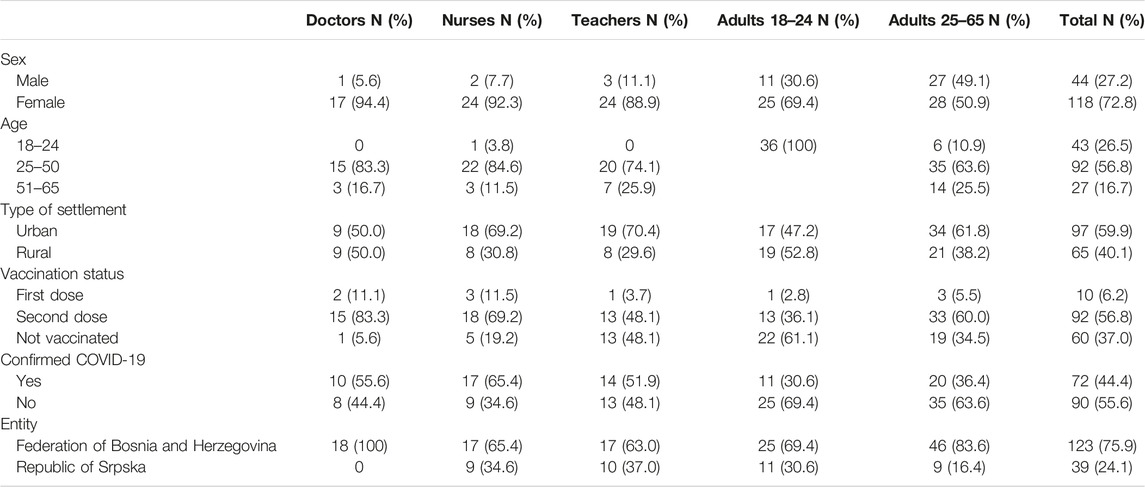

Focus group participants were identified using convenience and snowball sampling. A total of 162 participants participated in 16 focus groups at 10 locations, intentionally selected by researchers to represent various occupations, ages, administrative and geographic locations (both urban and rural), to provide a diversity of views and experiences. Detailed demographic information about the study participants is provided in Table 1 below. Of note, turnout among women was considerably higher than it was among men.

Participation in the study was voluntary. Ethical approval for conducting the study was provided by the Ethical Committee of the International University of Sarajevo. Potential benefits are that participants had the opportunity to share views, concerns and experiences that will influence the considerations of a strategy formulated as a result of this study. The participants received a gift certificate worth EUR 10 for their participation in the study.

The focus groups discussions were recorded by the moderator/researcher (NBC). A verbatim transcript of all audio recordings was made in the local language. All files and recordings were stored in password protected computers. Only the study team members had access to the recordings and transcripts. Copies of the recordings were deleted after all anonymous transcriptions were completed.

No identifiable data were collected. The collected demographic data on participants included age, sex, geographic location (rural/urban, entity), profession, information on confirmed COVID-19 infection, and vaccination status.

Researchers (SM, NBC, SD) analysed the transcripts using a deductive coding framework [12], which comprised a modified COM-B behavioural framework. Data were coded and tabulated in a rapid assessment matrix in three deductive phases. During the final phase, after creating the barrier tables, the researchers identified different sub-themes from the tables for each modified COM-B factor/four main themes. Tables with barriers were subsequently consolidated for the general population—aged 18–24 and 25–65, while HCWs and teachers are presented in separate tables.

Results

Target groups’ attitudes on COVID-19 vaccination barriers and drivers are presented below. Barriers are further presented in tables by the following COM-B factors/four main themes: [1] knowledge and health literacy concerning COVID-19 vaccines and vaccination; [2] attitudes and intentions towards COVID-19 vaccines and vaccination; [3] social support and social norms for COVID-19 vaccines (and recommending vaccination—for HCWs); [4] access to COVID-19 vaccination. Due to significantly lower number of drivers compared to barriers, they will be presented in the text only and will not be included in the tables. Of note, differences according to location (urban/rural) and professional group (doctors/nurses) are highlighted.

Barriers

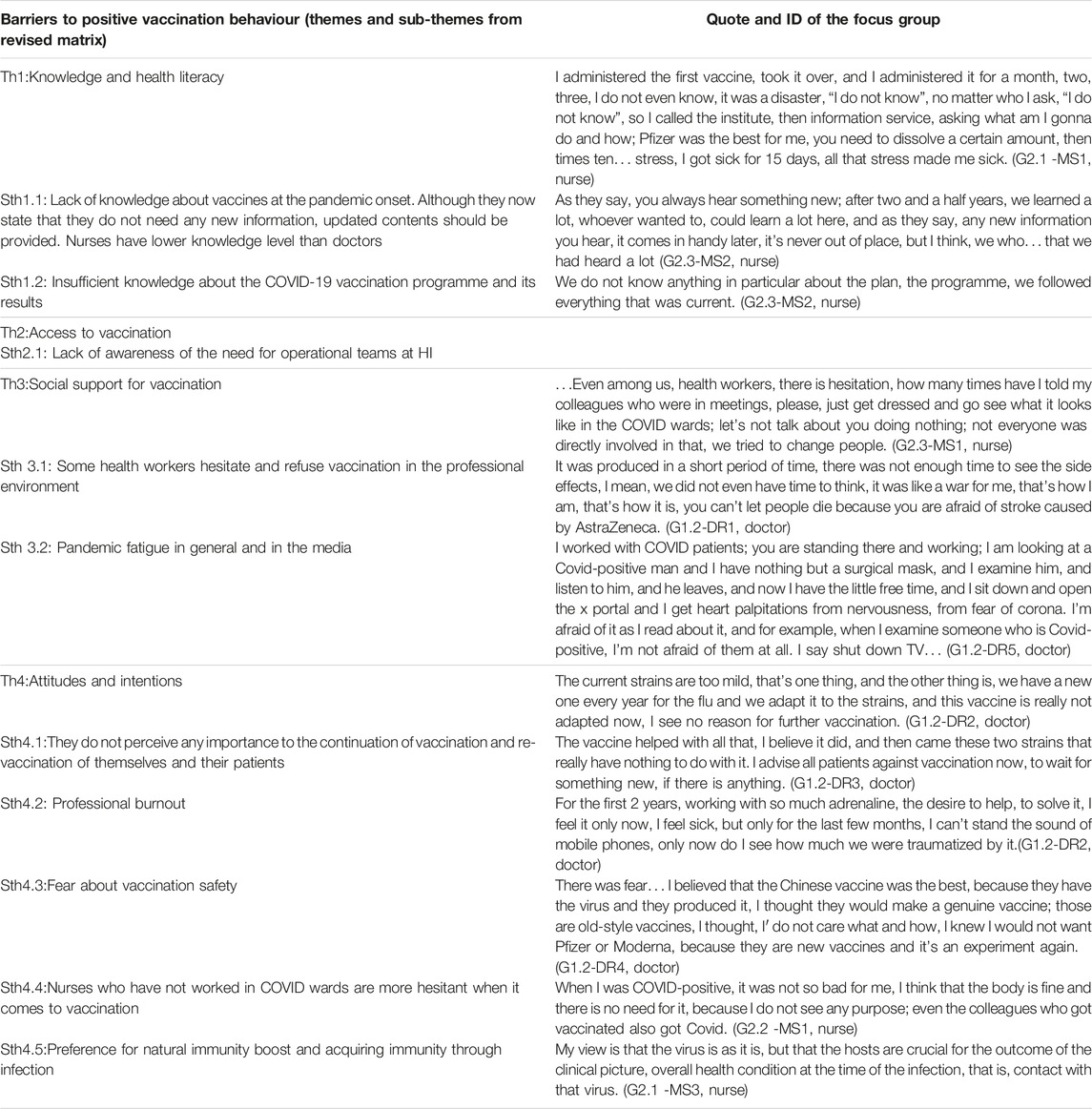

Healthcare Workers

All HCWs mentioned how difficult and stressful the period during the pandemic was, an experience they compare to the one they had during the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina (1992–1995). Almost all of them emphasized the lack of knowledge about vaccines at the pandemic onset. There was a general impression among HCWs that nurses are less informed about vaccines than doctors, which is also a potential barrier for promotion of vaccination among patients. Most HCWs participated in the teams that carried out vaccination to patients, but the majority were not familiar with the Vaccination Plan or results of the immunization programme.

A few HCWs expressed being hesitant when it comes to COVID-19 vaccination, and emphasized a lack of social support in the professional environment. Most mentioned professional burnout, as well as pandemic fatigue, both in general and in the media.

Most participants mentioned vaccination hesitancy among patients, emphasizing older individuals were the most interested in receiving the vaccine.

Most HCWs did not express any infection concerns for themselves or their patients. A number of HCWs, mainly nurses, mentioned fear about vaccination safety. A subgroup of nurses who worked in COVID hospital wards, however, did not report any hesitancy.

An overview of barriers to positive vaccination behaviour and illustrative quotes organized by COM-B factors are provided in Table 2.

Teachers

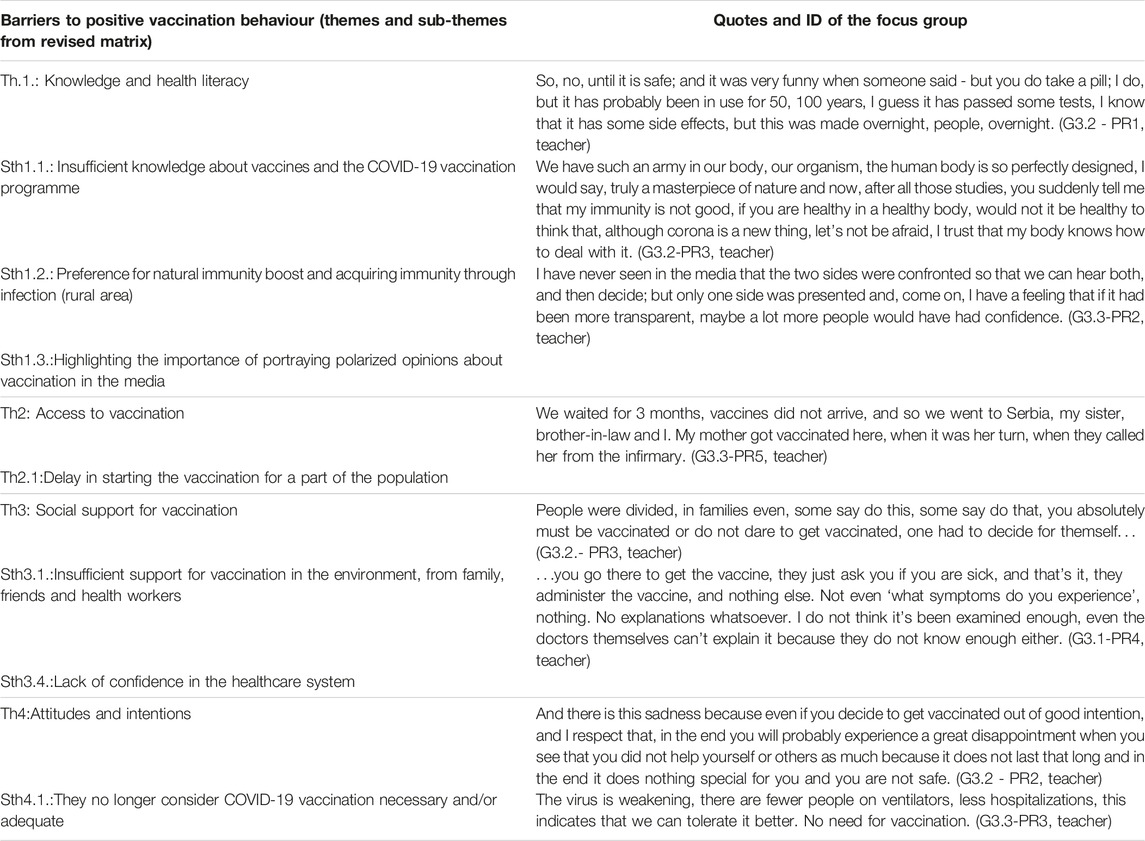

Regarding teachers who participated in the focus groups, most pointed out fear and uncertainty as dominant emotions during the pandemic, with some noting that the measures implemented to prevent the spread of infection were excessive, as well as the need for normalization of life.

Most participants were familiar with the types of vaccines available, but did not sufficiently display knowledge about vaccines and the country’s COVID-19 vaccination programme. Many teachers from rural areas had an extremely negative attitude towards vaccines. These teachers described media as being their main source of information. Some participants from rural areas overemphasized the boost of natural immunity through a healthy diet, while others emphasized the acquisition of immunity through infection and exposure. Some participants also mentioned wanting to hear a “different opinion” about vaccines in the public space. Some noted perceiving that vaccines were not available in time, and described getting vaccinated in a neighbouring country. Some waited for the vaccines to arrive in BiH, and described being vaccinated without any problems at a local healthcare facility.

Teachers stated that vaccination depends on one’s individual decision, and some mentioned problems related to lack of confidence in the healthcare system, as well as hesitancy of some HCWs to recommend vaccination. Insufficient support for vaccination from family, friends, and some HCWs also emerged as themes.

Most teachers described no longer being worried about infection, and did not consider vaccination to be necessary anymore. Barriers to vaccination included concerns about the rapid development of the vaccines, questionable effectiveness of the vaccines, and fear of adverse reactions.

Barriers to positive vaccination behaviour and illustrative quotes are provided in Table 3.

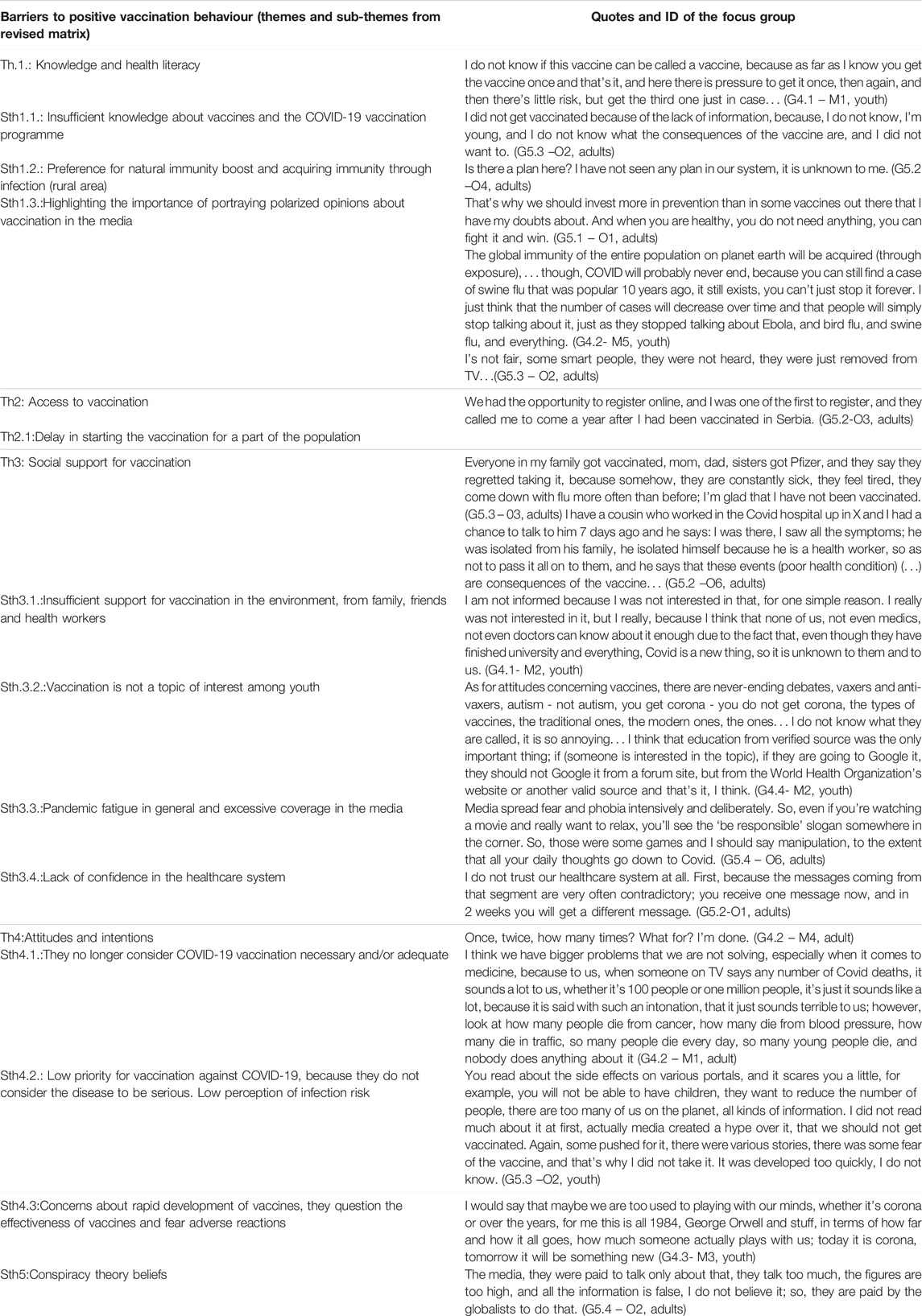

General Population (Youth, Adults)

Younger individuals who participated in focus groups reported stress due to online classes and lack of contact with teachers and peers during the pandemic.

Regarding COVID-19 vaccination, there was a lack of knowledge of detailed information about vaccines and vaccination against COVID-19 among younger focus group participants, including about: vaccine development, different types of vaccines available, protection offered by the vaccines, safety, and re-vaccination. The majority of younger participants pointed out that vaccination is no longer a topic of interest in their social circles, and mentioned the excessive coverage of the pandemic in the media.

A few participants noted that the beginning of vaccination was delayed, and that they were vaccinated in a neighbouring country. Those who were vaccinated in the country did not mention any problems with access to vaccination.

Many younger participants reported that they were not vaccinated, particularly those from rural areas. The main barriers to vaccination described were: lack of trust in COVID-19 vaccines, concerns about the speed of vaccine development and safety, and low priority for vaccination against COVID-19 because they do not consider the disease to be serious. Some younger participants noted that they preferred to acquire immunity by contracting the infection. Some younger participants cited a lack of trust in the healthcare system, as well as conspiracy theory beliefs.

Participants aged 25–65 reported negative experiences during the pandemic, including feelings of fear and uncertainty. They compared the situation to the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Those who lived in rural areas, especially in the countryside, coped with the anti-pandemic measures more easily. Lack of support for vaccination in the social environment stood out even among adults, as did fatigue related to the pandemic and its presence in the media.

Concerns about the rapid development of vaccines, as well as their safety and effectiveness, emerged as barriers to vaccination uptake, which was more significant in rural areas. Almost all participants currently had a low perception of infection risk, indicating low re-vaccination probability. Several participants mentioned lack of confidence in the healthcare system and a tendency to believe in conspiracy theories.

Barriers to positive vaccination behaviour and illustrative quotes are provided in Table 4.

TABLE 4. Barriers and illustrative quotes by COM-B—General population (Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2023).

Drivers

Healthcare Workers

Facilitators for COVID-19 vaccination receipt were aligned with participant confidence in science and professional recommendations of competent institutions, particularly among doctors.

There were some lectures organized through the zoom application. I remember one lecture, professor x explained each vaccine, its composition… We all basically read it, we all read about it ourselves online and then commented among ourselves… what type, what can you use, contraindications, our epidemiologist helped us a lot, she was like an ace up one’s sleeve, we called her in case of any ambiguity… (G1.2-DR3, doctor)

If scientists say that it is good, I am not competent to say that it is not. There are always side effects, even to paracetamol, of course there will be some to the vaccine… (G2.1-MS1, nurse)

In addition, the majority of participants noted that vaccination is necessary for pandemic control and prevention of severe disease outcomes, and that they considered this obligation as their professional duty.

Vaccines have always saved the world, smallpox was eradicated, right? Then let's get this going, people. (G1.2-DR3, doctor)

My mom said to me - take a sick leave, I can't take sick leave! It’s just like in the war - it’s my obligation. And you have to give your best, so it was very turbulent and difficult, you work under a uniform, with gloves, plaster sticks to you, you can't place IV properly, people die. (G2.2-NS3, nurse).

HCWs emphasized the importance of exchanging experience and information within the professional community, through both formal and informal communication channels:

Our group helped me a lot, a Viber group was created, I don't know who was the initiator, was it this colleague who is originally from BiH and works at the Mayo Clinic, or were there several people, and Zagreb and Belgrade and Sarajevo were all included, and then, that group really included everyone, from ‘small doctors’ who had just graduated, to the wow professors teaching different subjects, and you could really read about many different things there (…) we also had our own group, there were several, we had a health center’s group, which helped us a lot, for testing, and for vaccination, for information, and for the clinical picture, and transportation. I mean, what was done there, that group, family medicine, including ambulance, every information, we sent X-ray pictures, clinical pictures, received information... (G1.2-DR5, doctor)

Good organization of vaccination with operational teams within healthcare institutions emerged as one driver of vaccination uptake, but potential failure of those teams in the future (and not only when it comes to vaccination of HCWs against COVID-19, but also other diseases, e.g., flu) may be an aggravating factor for access to vaccination.

It was well organized, especially for health workers, and we all acted according to the plan, we were registered, names... We had priority, we got it right away, although it was AstraZeneca... and all kinds of (negative) things were said about it at the time…...(G2.1-DR1, doctor)

Teachers

Vaccination as a necessity for health protection and pandemic control, trust in science, and vaccination as a social norm emerged as vaccination drivers among teachers:

Simply, I have two options, either to take it regardless of the fact that it was quickly produced and that it has not yet been tested enough because it is the only way to do something for myself, to try to protect myself, or not to take it, to side with the group that says it's all a conspiracy theory and wait for my destiny (...), we have to trust scientists (...) so I decided to get vaccinated. (G3.3-PR1, teacher)

A number of participants mentioned the organization of vaccination for teachers:

In the beginning, when we made a list, and people whose names were on the list were called, as there were no vaccines at the beginning (for general population), and later, you could go and get it whenever you wanted... (G3.2-PR1, teacher)

In addition, participants who received the vaccination mentioned the following reasons for vaccination uptake: working conditions, travel, vulnerable family members, and their health.

General Population (Youth, Adults)

Among vaccinated participants aged 18–24, mostly among those who lived in urban areas, the motives for vaccination were their own health, travel possibilities, and workplace requirements:

At first, I didn't want to get vaccinated, and then my parents decided to get vaccinated, and when I saw that it was done without any problems, and some restrictions on accessing certain places and countries were imposed, I realized that my health condition could only get worse, I could contract the virus, so I decided to get vaccinated, these are both reasons (G4.1 – M3, youth)

Participants aged 25–65 who had received the vaccination noted the necessity of vaccination to protect their health and control the pandemic as motivating factors:

So, all those who were vaccinated will probably in some way strengthen their immune system in case of infection, they will have somewhat milder symptoms and will spread the infection less, so you have that one positive effect of this planetary vaccination and I think it worked, you know. Imagine if humanity had not been vaccinated at all, I think that the scale of the pandemic would have been much wider and much bigger; I think that on a global scale, I don't know the number of vaccinated people, 8-9 billion, maybe some 30-40% of people have already been vaccinated, this slowed down the pandemic spread and probably caused the virus to ‘weaken’. (G5.4 – O5, adults)

For some, vaccination was considered a social norm:

More or less, our view of all this is a civic one, that means we have to follow the instructions, we have to follow the management system, the rule of law and so on, and we have to behave like citizens. Whether it's right or wrong, whether it's true or not, that's more or less irrelevant now, that's just my opinion. (G5.4 – O3, adults)

In addition, participants described access to vaccination at their local healthcare centre as being mostly appropriate:

So, the process itself was simple, you apply, they call you, ask if I want re-vaccination, when the vaccine supplies arrive; Pfizer for example, in my case it was Pfizer, they call you and let you know that Pfizer supplies arrived. (G5.1 –O1, adults)

Those who had been vaccinated noted the importance of the presence of an informed HCW who elicits high levels of trust.

During the COVID period, I went to my family doctor who has been treating me for 15 years; I trust him, and I asked him if I should, he said yes; I asked which one? He says it doesn’t matter. This was our conversation about the vaccine. (G5.2-02, adults)

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study was among the first to examine barriers and facilitators to COVID-19 vaccination uptake among individuals in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Taken together, the results from this study suggest barriers to COVID-19 vaccination in this population, including: insufficient knowledge about the vaccines, the COVID-19 vaccination programme and its results, delays in starting the vaccination program, insufficient support for vaccination in private and professional settings, pandemic fatigue exacerbated by media coverage, concerns about the rapid development of the vaccine, its effectiveness and fear of side effects, low perception of infection risk, lack of confidence in the healthcare system, overemphasis on boosting natural immunity through healthy diet, preference for acquiring immunity through exposure to virus, the influence of polarized thoughts about vaccination in the media, and belief in conspiracy theories.

Further, our results identified the following as being drivers of COVID-19 vaccination: confidence in science and expert recommendations from competent institutions, the exchange of experience and information within the professional community through both formal and informal communication channels, a sense of obligation, and consideration of vaccination as a professional duty, particularly among doctors. HCWs and other target groups also emphasized the necessity of vaccination for pandemic control, health protection, prevention of severe disease outcomes, and its role as a social norm.

Our research was conducted with a population that has first or secondhand experience with the war in Bosnia. The pandemic experience, especially for HCWs, often triggered memories of this war, leading to feelings of fear, helplessness, and a lack of trust in public information. These factors may have hindered coping with the pandemic and resulted in the identification of more barriers than drivers among participants.

Both the barriers and drivers identified in our study align with the results of similar studies in Bosnia and Herzegovina [13–15]. These studies indicated that a small number of citizens, mainly those with higher education, higher income levels, and the elderly population, opted to get vaccinated against COVID-19, often motivated by the goal of achieving collective immunity. On the other hand, the majority of citizens expressed hesitancy or outright refusal to vaccinate [15]. Factors noted in the literature as contributing to and promoting hesitancy to vaccinate against COVID-19 include limited knowledge about vaccines and relatively pessimistic attitudes about vaccines [16]. Findings from other countries [17–20] also highlight factors associated with vaccine refusal and hesitancy, including concerns about vaccine safety, negative narratives related to various vaccines and their effectiveness, and individual’s personal knowledge about vaccination.

Furthermore, literature suggests that daily exposure to various misinformation about COVID-19 and vaccines led to confusion, anxiety, and vaccine mistrustful [21–23]. Most participants in the current study, regardless of their respective groups, mentioned the negative influence of media during the pandemic. Both the general public and HCWs were exposed to misinformation about COVID-19 and the development of related vaccines via media [24]. This created additional confusion and polarized thinking among people, which contributed to various conspiracy theories, which were also a barrier to vaccination. Research indicates that belief in conspiracy theories, especially those related the origin of the pandemic, is a significant barrier to vaccination [25–28]. Results of our study corroborate the presence of such beliefs.

Although perceived vaccination risk appears to have had a greater influence on individual’s willingness to vaccinate than the perceived risk of COVID-19 [29], studies also indicate that those who perceive a higher COVID-19 risk are less hesitant about vaccines. Many such individuals received or intend to receive the COVID-19 vaccine [29–33], as do those who express confidence in healthcare institutions and HCWs [33]. People more willing to get vaccinated tend to have higher education levels, express strong confidence in the vaccine, maintain a positive attitude toward the vaccine, fear COVID-19, personally (i.e., perceive COVID-19 risk), and have had contact with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients [33]. Similar to other European studies [34–37], our participants - doctors and HCWs who worked in COVID-19 wards - also expressed greater willingness to get vaccinated.

In our study, a significant portion of teachers, similar to HCWs, no longer (as of summer 2022) expressed significant concerns about COVID-19 infection and did not perceive vaccination as necessary, except for vulnerable groups. However, during the early stages of the pandemic, they did experience anxiety and raised concerns about the rapid development and effectiveness of vaccines. Similar studies involving teachers have yielded comparable results [38–40].

The ability to travel was one of the main COVID-19 vaccination drivers in our study across different groups. This aligns with findings from other studies where freedom of movement, travel opportunities, encouragement from family and friends, and positive past vaccination experiences have been identified as significant drivers for vaccination [41, 42].

The COVID-19 pandemic and immunization policies have undergone continuous changes, leading to shifts in public attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccines. This study contributes to the knowledge of key barriers and drivers for vaccination in Bosnia and Herzegovina during the summer of 2022. As vaccination efforts persist in Bosnia and Herzegovina, addressing key barriers for HCWs remains critical. Accordingly, interventions should involve regular updates of information on official websites, the organization of symposiums and immunization training programs, as well as fostering cooperation and engagement with medical chambers and associations. Recommendations and encouragement for vaccination (e.g., through official letters) by competent ministries, public health institutes, associations, professional bodies, and certification of education on immunization by professional chambers should also be taken into consideration. One of the ways to exchange information and knowledge is through online learning communities, using mobile phone applications (Viber and WhatsApp).

This study has some limitations. The study was conducted within a short time frame during the summer vacation season, which posed challenges in achieving the desired participation level due to project constraints. This was, however, compensated for by including more locations with a lesser number of people per focus group than initially envisioned. More women participated in our focus groups than did men. However, in the case of HCWs and teachers, this discrepancy can be partly attributed to the higher representation of women in these professions. Regarding reflexivity, we made efforts to remain aware of our potential biases throughout the research process. While we continually questioned and edited materials to mitigate bias, our prior and recent experiences, assumptions, and beliefs about COVID-19 vaccines may have still influenced the research process.

Good organization of access to vaccination, sufficient time for vaccination, wide availability, and flexible working hours at vaccination points during any pandemic should continue to be standard practices. Additionally, vaccination reminders and invitations via phone calls, texts or emails are crucial. Vaccination promotion campaigns seem to also have a positive effect [43], and over the past 2 years, with the support of international agencies, health authorities in Bosnia and Herzegovina conducted comprehensive campaigns targeting various demographics. The importance of communication about immunization and presence of a HCW with effective communication skills are evident from our study. With the main focus now predominantly on individuals at risk of contracting disease, different communication channels should be used, as well as work with individuals and communities through dialogue, with mutual respect and appreciation of different opinions. Given that the WHO declared an end to COVID-19 as a public health emergency 9 months after the data collection, we encourage further research to monitor the evolution of vaccine related attitudes, inform immunization policy, and develop evidence-based interventions.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving humans were approved by International University of Sarajevo ethical committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

SM: Conception and design of the work, data analysis and interpretation, and drafting the article. NB-C: Design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, and drafting the article. SD: Data collection and drafting the article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

1. Watson, OJ, Barnsley, G, Toor, J, Hogan, AB, Winskill, P, and Ghani, AC. Global Impact of the First Year of COVID-19 Vaccination: A Mathematical Modelling Study. Lancet Infect Dis (2022) 22(9):1293–302. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00320-6

2. Sallam, M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Worldwide: A Concise Systematic Review of Vaccine Acceptance Rates. Vaccines (Basel) (2021) 9(2):160. doi:10.3390/vaccines9020160

3. Lazarus, JV, Wyka, K, White, TM, Picchio, CA, Rabin, K, Ratzan, SC, et al. Revisiting COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Around the World Using Data From 23 Countries in 2021. Nat Commun (2022) 13(1):3801. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-31441-x

4. Dooling, K, McClung, N, Chamberland, M, Marin, M, Wallace, M, Bell, BP, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices' Interim Recommendation for Allocating Initial Supplies of COVID-19 Vaccine - United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep (2020) 69(49):1857–9. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6949e1

5. Wise, J. COVID-19: Health and Care Workers Will Be ‘highest Priority’ for Vaccination, Says JCVI. BMJ (2020) 369:m2477. doi:10.1136/bmj.m2477

6. Paterson, P, Meurice, F, Stanberry, LR, Glismann, S, Rosenthal, SL, and Larson, HJ. Vaccine Hesitancy and Healthcare Providers. Vaccine (2016) 34(52):6700–6. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.042

7. McCready, JL, Nichol, B, Steen, M, Unsworth, J, Comparcini, D, and Tomietto, M. Understanding the Barriers and Facilitators of Vaccine Hesitancy Towards the COVID-19 Vaccine in Healthcare Workers and Healthcare Students Worldwide: An Umbrella Review. PLoS One (2023) 18(4):e0280439. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0280439

8. Jeremic Stojkovic, V, Cvjetkovic, S, Jankovic, J, Mandic-Rajcevic, S, Matovic Miljanovic, S, Stevanovic, A, et al. Attitudes Towards COVID-19 Vaccination and Intention to Get Vaccinated in Western Balkans: Cross-Sectional Survey. Eur J Public Health (2023) 33(3):496–501. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckad066

9. World Health Organization. Bosnia and Herzegovina Situation (2023). Available From: https://covid19.who.int/region/euro/country/ba (Accessed September 25, 2023).

10. Habersaat, KB, and Jackson, C. Understanding Vaccine Acceptance and Demand—And Ways to Increase Them. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz (2020) 63(1):32–9. doi:10.1007/s00103-019-03063-0

11. World Health Organization. Rapid Qualitative Research to Increase COVID-19 Vaccination Uptake: A Research and Intervention Tool. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe (2022). License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

12. Elo, S, and Kyngäs, H. The Qualitative Content Analysis Process. J Adv Nurs (2008) 62(1):107–15. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

13. Hrvat, F, Aleta, A, Džuho, A, Hasanić, O, and Bećirović, LS. First Report on Public Opinion Regarding COVID-19 Vaccination in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In: A Badnjevic, and LG Pokvić, editors. International Conference on Medical and Biological Engineering 2021. Cham: Springer (2021). p. 907–20.

14. Fojnica, A, Osmanovic, A, Đuzic, N, Fejzic, A, Mekic, E, Gromilic, Z, et al. Lack of Lockdown, Open Borders, and No Vaccination in Sight: Is Bosnia and Herzegovina a Control Group? medRxiv (2021). doi:10.1101/2021.03.01.21252700

15. Fojnica, A, Osmanovic, A, Đuzic, N, Fejzic, A, Mekic, E, Gromilic, Z, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Rejection in an Adult Population in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Plos one (2022) 17(2):e0264754. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0264754

16. Sljivo, A, Cetkovic, A, Abdulkhaliq, A, Kiseljakovic, M, Selimovic, A, and Kulo, A. COVID-19 Vaccination Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Among Residents of Bosnia and Herzegovina During the Third Wave of COVID-19 Outbreak. Ann Ig (2021) 34. doi:10.7416/ai.2021.2489

17. Marzo, RR, Ahmad, A, Islam, MS, Essar, MY, Heidler, P, King, I, et al. Perceived COVID-19 Vaccine Effectiveness, Acceptance, and Drivers of Vaccination Decision-Making Among the General Adult Population: A Global Survey of 20 Countries. PLoS Negl Trop Dis (2022) 16(1):e0010103. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0010103

18. Fisher, KA, Bloomstone, SJ, Walder, J, Crawford, S, Fouayzi, H, and Mazor, KM. Attitudes Toward a Potential SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine: A Survey of US Adults. Ann Intern Med (2020) 173(12):964–73. doi:10.7326/M20-3569

19. Neumann-Böhme, S, Varghese, NE, Sabat, I, Barros, PP, Brouwer, W, van Exel, J, et al. Once We Have it, Will We Use it? A European Survey on Willingness to Be Vaccinated Against COVID-19. Eur J Health Econ (2020) 21(7):977–82. doi:10.1007/s10198-020-01208-6

20. Wang, J, Jing, R, Lai, X, Zhang, H, Lyu, Y, Knoll, MD, et al. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination During the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Vaccines (2020) 8(3):482. doi:10.3390/vaccines8030482

21. Al-Qerem, WA, and Jarab, AS. COVID-19 Vaccination Acceptance and Its Associated Factors Among a Middle Eastern Population. Front Public Health (2021) 9:632914. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.632914

22. Lockyer, B, Islam, S, Rahman, A, Dickerson, J, Pickett, K, Sheldon, T, et al. Understanding COVID-19 Misinformation and Vaccine Hesitancy in Context: Findings From a Qualitative Study Involving Citizens in Bradford, UK. Health Expect (2021) 24(4):1158–67. doi:10.1111/hex.13240

23. Palamenghi, L, Barello, S, Boccia, S, and Graffigna, G. Mistrust in Biomedical Research and Vaccine Hesitancy: The Forefront Challenge in the Battle Against COVID-19 in Italy. Eur J Epidemiol (2020) 35(8):785–8. doi:10.1007/s10654-020-00675-8

24. Evanega, S, Lynas, M, Adams, J, Smolenyak, K, and Insights, CG. Coronavirus Misinformation: Quantifying Sources and Themes in the COVID-19 Infodemic. JMIR Preprints (2020) 19(10):2020.

25. Romer, D, and Jamieson, KH. Conspiracy Theories as Barriers to Controlling the Spread of COVID-19 in the US. Soc Sci Med (2020) 263:113356. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113356

26. Yang, Z, Luo, X, Jia, H, and Wang, Y. Deep Learning on SDF for Classifying Brain Biomarkers. Vaccines (2021) 9(10):1051–4. doi:10.1109/EMBC46164.2021.9630850

27. Haakonsen, JM, and Furnham, A. COVID-19 Vaccination: Conspiracy Theories, Demography, Ideology, and Personality Disorders. Health Psychol (2022) 42:205–12. doi:10.1037/hea0001222

28. Farhart, CE, Douglas-Durham, E, Trujillo, KL, and Vitriol, JA. Vax Attacks: How Conspiracy Theory Belief Undermines Vaccine Support. Prog Mol Biol Translational Sci (2022) 188(1):135–69. doi:10.1016/bs.pmbts.2021.11.001

29. Detoc, M, Bruel, S, Frappe, P, Tardy, B, Botelho-Nevers, E, and Gagneux-Brunon, A. Intention to Participate in a COVID-19 Vaccine Clinical Trial and to Get Vaccinated Against COVID-19 in France During the Pandemic. Vaccine (2020) 38(45):7002–6. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.041

30. Ward, JK, Alleaume, C, Peretti-Watel, P, Seror, V, Cortaredona, S, Launay, O, et al. The French Public's Attitudes to a Future COVID-19 Vaccine: The Politicization of a Public Health Issue. Soc Sci Med (2020) 265:113414. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113414

31. Guillon, M, and Kergall, P. Factors Associated With COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions and Attitudes in France. Public health (2021) 198:200–7. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2021.07.035

32. Williams, SN, and Dienes, K. Public Attitudes to COVID-19 Vaccines: A Qualitative Study (2021). Available From: https://psyarxiv.com/h87s3/ (Accessed April 06, 2023).

33. Musa, S, Cilovic-Lagarija, S, Kavazovic, A, Bosankic-Cmajcanin, N, Stefanelli, A, Scott, NA, et al. COVID-19 Risk Perception, Trust in Institutions and Negative Affect Drive Positive COVID-19 Vaccine Intentions. Int J Public Health (2022) 67:1604231. doi:10.3389/ijph.2022.1604231

34. Musa, S, Skrijelj, V, Kulo, A, Habersaat, KB, Smjecanin, M, Primorac, E, et al. Identifying Barriers and Drivers to Vaccination: A Qualitative Interview Study With Health Workers in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Vaccine (2020) 38(8):1906–14. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.01.025

35. Maltezou, HC, Pavli, A, Dedoukou, X, Georgakopoulou, T, Raftopoulos, V, Drositis, I, et al. Determinants of Intention to Get Vaccinated Against COVID-19 Among Healthcare Personnel in Hospitals in Greece. Infect Dis Health (2021) 26(3):189–97. doi:10.1016/j.idh.2021.03.002

36. Butter, S, McGlinchey, E, Berry, E, and Armour, C. Psychological, Social, and Situational Factors Associated With COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions: A Study of UK Key Workers and Non-Key Workers. Br J Health Psychol (2022) 27(1):13–29. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12530

37. Galanis, P, Vraka, I, Fragkou, D, Bilali, A, and Kaitelidou, D. Intention of Health Care Workers to Accept COVID-19 Vaccination and Related Factors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. MedRxiv (2021). p. 2020–12.

38. Estrela, M, Silva, TM, Roque, V, Gomes, ER, Figueiras, A, Roque, F, et al. Unravelling the Drivers Behind COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy and Refusal Among Teachers: A Nationwide Study. Vaccine (2022) 40(37):5464–70. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.07.059

39. Racey, CS, Donken, R, Porter, I, Albert, A, Bettinger, JA, Mark, J, et al. Intentions of Public School Teachers in British Columbia, Canada to Receive a COVID-19 Vaccine. Vaccin X (2021) 8:100106. doi:10.1016/j.jvacx.2021.100106

40. Weinert, S, Thronicke, A, Hinse, M, Schad, F, and Matthes, H. School Teachers’ Self-Reported Fear and Risk Perception During the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Nationwide Survey in Germany. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2021) 18(17):9218. doi:10.3390/ijerph18179218

41. Stämpfli, D, Martinez-De la Torre, A, Simi, E, Du Pasquier, S, Berger, J, and Burden, AM. Community Pharmacist-Administered COVID-19 Vaccinations: A Pilot Customer Survey on Satisfaction and Motivation to Get Vaccinated. Vaccines (2021) 9(11):1320. doi:10.3390/vaccines9111320

42. Stoner, MC, Browne, EN, Tweedy, D, Pettifor, AE, Maragh-Bass, AC, Toval, C, et al. Exploring Motivations for COVID-19 Vaccination Among Black Young Adults in 3 Southern US States: Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Formative Res (2022) 6(9):e39144. doi:10.2196/39144

Keywords: COVID-19, barriers, drivers, vaccine uptake, vaccines

Citation: Bosankic-Cmajcanin N, Musa S and Draganovic S (2023) In the Face of a Pandemic: “I Felt the Same as When the War Started”—A Qualitative Study on COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Int J Public Health 68:1606411. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2023.1606411

Received: 18 July 2023; Accepted: 04 October 2023;

Published: 13 October 2023.

Edited by:

L. Suzanne Suggs, University of Italian Switzerland, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Rowena Katherine Merritt, University of Kent, United KingdomOne reviewer who chose to remain anonymous

Copyright © 2023 Bosankic-Cmajcanin, Musa and Draganovic. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nina Bosankic-Cmajcanin, bi5ib3NhbmtpY0BnbWFpbC5jb20=

Nina Bosankic-Cmajcanin

Nina Bosankic-Cmajcanin Sanjin Musa

Sanjin Musa Selvira Draganovic1

Selvira Draganovic1