Patient safety is a priority in all healthcare systems. Despite this, up to 24% of hospital admissions and around 7% of primary care patients experience adverse events (AEs) annually, with approximately 50% being preventable [1, 2]. In the EU alone, these preventable AEs result in a loss of 1.5 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and a cost of 19.53–43.65 billion euros in 2024 [3], with a significant impact on the quality of care.

Most of these preventable AEs are due to suboptimal working conditions [4]. Uncertainty, overload, fatigue, and complexity are common limiting factors for quality care, including patient safety. Healthcare workers often face psychological trauma from events such as life-threatening incidents, needle sticks, dramatic deaths, violence, patient deterioration, resuscitations, complaints, suicidal tendencies, and errors causing patient harm. These can alter the practice and morale of healthcare workers, impacting patient outcomes. Therefore, workforce resilience is key to providing optimal care. Otherwise, when overwhelmed and lacking coping resources, they become second victims [5]. They are “any healthcare worker directly or indirectly involved in an unanticipated adverse patient event, unintentional healthcare error, or patient injury, who becomes victimized in the sense that they are also negatively impacted.”

Organizational factors and personality traits influence the second victim experience. Providing safe working conditions is part of the WHO’s objectives for safer care [6]. Professionals must feel supported, trained, equipped, protected, rested, and provided with a suitable work environment, reducing the intensity of this experience as second victims. Addressing this involves healthcare authorities, health professions, scientific societies, academia, patient associations, and civil society and requires a commitment to self-care, prevention programs, and emotional support interventions.

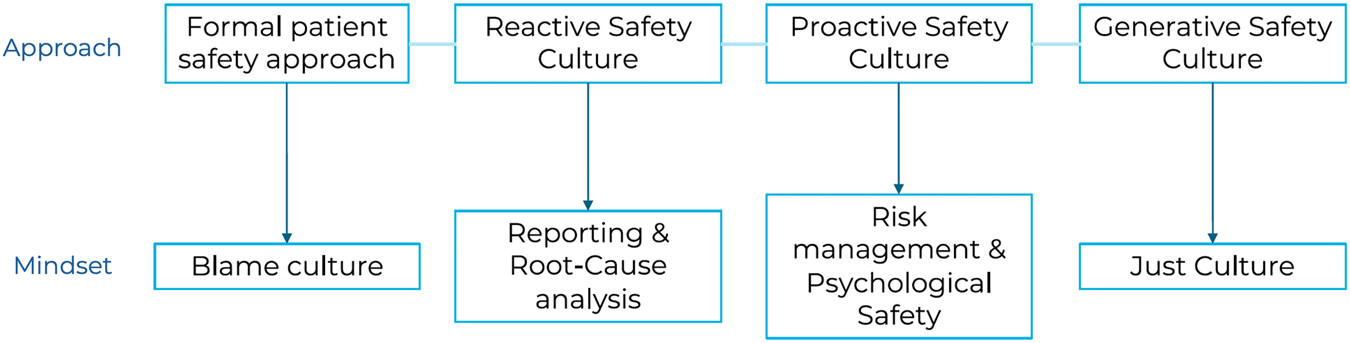

Safety culture, particularly Psychological Safety, is crucial. Introduced by Amy Edmondson [7] in 1999, it describes the ability to speak without fear about performance, including mistakes, to improve care. Without this, patient safety is at risk [8, 9]. However, the blame culture remains prevalent in healthcare [10], impacting how professionals address safety incidents. Fear of blame hinders progress toward a safety culture. Many institutions comply with WHO’s safe practices but fail to engage professionals in patient safety, reacting to dramatic events without preventing potential harm. Proactive risk management fosters a culture of safety. These organizations are on the verge of sharing a culture that generates safety (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

Patient safety path: from formal culture to generative culture of patient safety (Europe, 2024).

Since healthcare workers are not adequately trained to warn colleagues of risky behavior, manage reactions, or support second victims (Kupkovicova et al.; Carrillo et al.) [11], educational reforms are needed to address identified educational gaps in patient safety and to integrate second victim support into the training of medical, nursing, and other healthcare students. Equipping future professionals with skills to recognize and address the second victim phenomenon fosters a supportive work environment and improves patient safety outcomes. Ultimately, these changes can lead to improved quality of care, better patient safety outcomes, and a more resilient healthcare workforce.

To support healthcare professionals and prioritize patient safety and wellbeing, organizations must:

1. Create a fair and accountable environment: Implement policies ensuring transparency and fairness in evaluating performance and handling errors, fostering trust and openness.

2. Balance safety and accountability: Understand root causes of errors and address systemic issues to prevent recurrence, balancing individual accountability with systemic improvements.

3. Commit to continuous improvement and transparency: Regularly evaluate safety protocols, using incident data to drive change, and promote openness to build trust.

4. Learn from incidents: Analyze incidents, identify contributing factors, and develop risk mitigation strategies, empowering staff to participate in safety initiatives.

5. Promote fairness in incident response: Distinguish between honest mistakes, at-risk behavior, and reckless behavior, focusing on system-wide improvements and creating a supportive environment.

By implementing these strategies, healthcare organizations can better support professionals and cultivate a just culture, benefiting patients. Encouraging self-care, resilience, and emotional support, along with fairness and continuous improvement, creates a more effective and compassionate healthcare system.

Statements

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

References

1

Bates DW Levine DM Salmasian H Syrowatka A Shahian DM Lipsitz S et al The Safety of Inpatient Health Care. N Engl J Med (2023) 388(2):142–53. PMID: 36630622. 10.1056/NEJMsa2206117

2

Panagioti M Khan K Keers RN Abuzour A Phipps D Kontopantelis E et al Prevalence, Severity, and Nature of Preventable Patient Harm Across Medical Care Settings: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ (2019) 366:l4185. PMID: 31315828; PMCID: PMC6939648. 10.1136/bmj.l4185

3

Agbabiaka TB Lietz M Mira JJ Warner B . A Literature-Based Economic Evaluation of Healthcare Preventable Adverse Events in Europe. Int J Qual Health Care (2017) 29(1):9–18. PMID: 28003370. 10.1093/intqhc/mzw143

4

Hickam DH Severance S Feldstein A Ray L Gorman P Schuldheis S et al The Effect of Health Care Working Conditions on Patient Safety: Summary. In: AHRQ Evidence Report Summaries, 74. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US) (1998-2005) (2003). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11929/ (Accessed July 30, 2024).

5

Vanhaecht K Seys D Russotto S Strametz R Mira J Sigurgeirsdóttir S et al An Evidence and Consensus-Based Definition of Second Victim: A Strategic Topic in Healthcare Quality, Patient Safety, Person-Centeredness and Human Resource Management. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2022) 19(24):16869. 10.3390/ijerph192416869

6

World Health Organization. Global Patient Safety Action Plan 2021-2030: Towards Eliminating Avoidable Harm in Health Care. Geneva (2021).

7

Edmondson A . Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Adm Sci Q (1999) 44(2):350–83. 10.2307/2666999

8

Pacutova V Geckova AM de Winter AF Reijneveld SA . Opportunities to Strengthen Resilience of Health Care Workers Regarding Patient Safety. BMC Health Serv Res BMC Health Serv Res (2023) 23(1):1127. PMID:37858175. 10.1186/s12913-023-10054-0

9

Dietl JE Derksen C Keller FM Lippke S . Interdisciplinary and Interprofessional Communication Intervention: How Psychological Safety Fosters Communication and Increases Patient Safety. Front Psychol (2023) 14:1164288. PMID: 37397302; PMCID: PMC10310961. 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1164288

10

van Marum S Verhoeven D de Rooy D . The Barriers and Enhancers to Trust in a Just Culture in Hospital Settings: A Systematic Review. J Patient Saf (2022) 18(7):e1067–e1075. Epub 2022 May 19. PMID: 35588066. 10.1097/PTS.0000000000001012

11

Sánchez-García A Saurín-Morán PJ Carrillo I Tella S Põlluste K Srulovici E et al Patient Safety Topics, Especially the Second Victim Phenomenon, Are Neglected in Undergraduate Medical and Nursing Curricula in Europe: An Online Observational Study. BMC Nurs (2023) 22(1):283. PMID: 37620803; PMCID: PMC10464449. 10.1186/s12912-023-01448-w

Summary

Keywords

psychological safety, second victim, healthcare workers, quality of care, safety culture

Citation

Mira J, Madarasova Geckova A, Knezevic B, Sousa P and Strametz R (2024) Editorial: Psychological Safety in Healthcare Settings. Int J Public Health 69:1608073. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2024.1608073

Received

21 October 2024

Accepted

04 November 2024

Published

02 December 2024

Volume

69 - 2024

Edited by

Nino Kuenzli, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (Swiss TPH), Switzerland

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Mira, Madarasova Geckova, Knezevic, Sousa and Strametz.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andrea Madarasova Geckova, andrea.geckova@upjs.sk

This Special Issue Editorial is part of the IJPH Special Issue “Psychological Safety in Healthcare Settings”

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.