Abstract

Objectives:

This study aims to analyze the demands of older people for care services and to evaluate and position care facilities to accommodate the requirements of healthy aging.

Methods:

Data on the demand for care services in Chengdu were collected. Fuzzy-set qualitative comparison analysis was used for demands analysis. Probabilistic linguistic term sets were used to assess and position facilities. Finally, the recommendations methods were provided by different demands of older people.

Results:

There were four paths to produce the high demands for care services of older people. Among the six types of services, medical services, psychological counseling, and nursing services had the greatest impact, while diet conditions had the least. The older people with clear demands can select facilities by the first recommendation method, while those with unclear demands can choose from four types of facilities: recommended, non-recommended, suitable for forward-thinking customers, and suitable for concerned customers.

Conclusion:

This study provides valuable insights into older people, care facilities, and governments. The older people can choose suitable facilities by their demands, while facilities can enhance service quality accordingly. Governments can allocate resources efficiently and promote healthy aging.

Introduction

The aging population phenomenon and the concomitant decline in birth rates have led to an escalation in the aging process across virtually all nations [1]. Furthermore, countries across the globe actively promote and implement policies and protocols to address the challenges posed by the aging population [2, 3]. At the end of 2022, China’s population aged 60 and over was about 280 million, accounting for 19.8% of the total population. This number is expected to reach 400 million by 2035. Meanwhile, as the number of older people increases, the demands for healthcare services are also rising rapidly [4], which provides new challenges and opportunities for care facilities [5, 6]. Despite the Chinese cultural emphasis on filial piety and home-based care, evidence suggests that family support systems are increasingly inadequate for the care of older people in China [7]. As a result, care facilities are necessary as places of professional care for older people with chronic diseases, disabilities, and other problems. It is essential for care facilities to meet the demands for care services [8]. Therefore, balancing the supply and demands of care service for older people has become the key to promoting the development of the care service system.

However, the growing diversity of older people’s care demands, coupled with a decline in the service quality of care facilities, has led to an imbalance between the supply of and demand for healthcare for older people [9, 10]. Effectively addressing this issue requires a comprehensive understanding of older people’s specific demands and preferences. Previous studies have explored the factors influencing older people’s care demands, with surveys conducted in various regions across nations [11–14]. These studies have consistently demonstrated that care service demands are influenced by factors such as gender, age, education, occupation, economic status, and activities of daily living [15–19]. Furthermore, previous research has examined spatial planning for care facilities, the requirements for in-home care, and the impact of healthcare services on care demands [20–23].

In developing countries like China, care services for older people have increasingly become the focus of social attention due to the rapid pace of aging [24]. However, a significant gap remains in research concerning the balance between the care demands of older people and the services provided. Some research on care services primarily emphasizes medical care for frail, empty-nest, dementia-affected, and disabled older people [25–28]. With accelerated economic development and urbanization, the lifestyles and care service demands of older people have evolved. Simultaneously, the change of cultural concepts has promoted the pursuit of quality and individuation of care services for older people. Therefore, it is imperative to explore more effective care service models that address the challenges posed by the diverse demands of older people.

To address these limitations, this study constructs an overall evaluation system for care services according to the demands of older people. The innovations of our work are highlighted as follows: 1) According to the demands of older people, the critical evaluation indicators and their weights of care facilities are obtained; 2) For the older people with clear demands, we will support selecting care facilities according to their demands; 3) For the older people with non-clear demands, the orientation of care facilities is provided; 4) Care facilities are positioned and divided into four types to meet different types of older people. The study’s findings will advance the field of care services to provide better support for healthy aging.

Methods

Data Collection

With the improvement of medical technology and living standards, the number of older people is increasing. Taking Jinjiang District of Chengdu as an example, the population over 60 years old accounted for 20.86 percent of the total population by the end of 2022. Considering the changes in the social structure, the survey objects of this study include people aged 50 to 59 in addition to those over 60 years old. To ensure the success of the investigation, this study chooses random sampling to conduct offline and online surveys. Participants were randomly selected from the identified survey locations and online channels. The offline survey was conducted primarily in two communities with a higher proportion of older people (Jinguanyi and Jiaozi Community), a city park (Wangjiang Tower Park), and a senior center (Jiaozi Community). The online survey was conducted using Wenjuanxing (a professional online survey platform in China). Participants were recruited through community WeChat groups and local community announcements. All participants were informed of the study’s purpose, voluntary nature, and anonymity.

The questionnaire included the respondents’ demographics (age, gender, and education level), family structures (living arrangement and number of children), financial status (monthly income), demands and perceptions for care services. Three rounds of data collection were conducted in 2023 in March, July, and September. A total of 26 questionnaires were distributed in the first round of the survey, which served as a preliminary survey to improve the questionnaire design but were excluded from the results analysis. A total of 267 questionnaires were collected in the second and third rounds, including 223 qualified questionnaires. Participants were primarily younger older people (under 70 years old). The proportion of women was slightly higher than men, at 56.95%. Most participants had a secondary school education, representing 50.22% of the sample. Moreover, most of the participants’ monthly income is between 3,001 and 4000 CNY, accounting for 45.74%. The most common family structure involved one surviving child, with 35.43% of participants, and most participants lived either with their mate or with their children. Detailed demographic characteristics can be found in the Supplementary Appendix (Supplementary Table S1). Meanwhile, five experts with backgrounds in nursing, gerontology, and business management were employed to evaluate 10 care facilities .

Variables

The outcome variable was the degree of care service demand among older people. Participants assessed their overall care service demands using a three-point scale: 1 (low), 2 (general), and 3 (high). The condition variables are the degrees of demands for the six types of care services provided by facilities, including medical services , psychological counseling , social activities , living conditions , diet conditions , and nursing services . Responses are provided on a five-point Likert scale (1 = “very not needed” to 5 = “very needed”). Related contents are shown in the Supplementary Materials.

To ensure the reliability of the measurements, we conducted reliability and validity analysis for the six condition variables. The overall Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.852, and the Cronbach’s α for each condition variable ranged from 0.757 to 0.841, indicating good internal consistency [29]. Confirmatory factor analysis was used to check the validity of the measured items. The results revealed that all the factor loadings were above 0.701, demonstrating significant relationships between items and their latent constructs. Further, all condition variables exhibited average variance extraction (AVE) values greater than 0.587 and composite reliability (CR) values greater than 0.721, showing good construct reliability [30]. These results confirm the reliability of the scales. The detailed results can be found in the Supplementary Appendix (Supplementary Table S2).

Demands Analysis

Fuzzy-set qualitative comparison analysis (fsQCA) is a variant of qualitative comparison analysis that describes the paths that produce the intended results, emphasizing combinations superior to single contributions [31]. Moreover, it emphasizes case-oriented comparative analysis from a holistic perspective [32]. Compared to other qualitative methods, fsQCA can explore complex combinations of multiple care service demands, identify configurations of different services, and work with small to medium sample sizes. Hence, it is suitable to address multi-factor complexity problems.

This study uses the direct calibration method to convert each variable into a fuzzy set. Three calibration anchors are determined using 90%, 50%, and 10% of the result and condition variable scores, corresponding to complete membership, cross point, and non-membership. Since all the consistency values are smaller than 0.9 in necessity analysis results, it indicates that any condition variable does not constitute the necessity condition of the outcome variable [33]. The truth table has 64 different combinations of conditions. The outcome variable is encoded as 1 when raw consistency is greater than 0.8 and PRI consistency is greater than 0.7 and both are met simultaneously; otherwise, it is encoded as 0. The configuration analysis aims to show specific results produced by various combinations of condition variables. After eliminating situations that do not reach the frequency and consistency threshold, the complex, intermediate, and parsimonious solutions are generated by the results of configuration analysis. First, the configuration of condition variables is classified using the intermediate solution. Next, the parsimonious solution is used to distinguish between the core and edge conditions for the condition variables. Table 1 shows the results of the configuration.

TABLE 1

| Variables | Paths | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Medical services | ● | ● | ● | |

| Psychological counseling | ● | ● | ● | ⊗ |

| Social activities | ● | ● | ⊗ | |

| Living conditions | ● | ● | ⊗ | |

| Diet conditions | ● | ⊗ | ● | ⊗ |

| Nursing services | ⊗ | ● | ● | • |

| Consistency | 0.907 | 0.887 | 0.880 | 0.857 |

| Raw coverage | 0.227 | 0.216 | 0.281 | 0.224 |

| Unique coverage | 0.054 | 0.044 | 0.071 | 0.087 |

| Consistency of solution | 0.860 | |||

| Coverage of solution | 0.490 | |||

Results of configuration (China, 2023).

Notes: Intermediate solution and parsimonious solution. The symbol ● means that the core condition variable exists and is assigned a score of 5; The symbol • means that the edge condition variable exists and is assigned a score of 4; Blank space means that the condition variable is optional and is assigned a score of 3; The symbol ⨰ means that the edge condition variable does not exist and is assigned a score of 2; The symbol ⊗ means that the core condition variable does not exist and is assigned a score of 1.

According to Table 1, there are four paths for the high demands, and the consistency of the solution is greater than 0.8. It reflects that all paths are sufficient conditions for forming high demands.

Assessment and Positioning of Care Facilities

As a flexible tool to express people’s linguistic information, probabilistic linguistic term sets (PLTSs) [34] and some extension theories have been widely used in various practical problems [35, 36]. To effectively capture the uncertainty and vagueness in older people’s linguistic expressions and to describe their preferences, this study adopts the PLTSs [34, 37, 38]. PLTSs allow for expressing evaluations with multiple linguistic terms along with their associated probabilities.

For example, let be the linguistic term set used to evaluate facilities. Suppose that the PLTS for the facility in respect of the attribute is expressed as , then it means that the facility performs “poor” in the attribute with a probability of 0.4 and “general” with a probability of 0.6. Moreover, the belief interval interpretation indicates that the belief interval for the facility to perform “poor” in the attribute is , and the belief interval for it to perform “good” is . The use of belief interval interpretation allows for a more flexible and nuanced representation of the probabilistic linguistic information. For convenience, the belief interval interpretation for each decision matrix is expressed as .

Older people who choose care facilities can generally be divided into two groups. The first group consists of clear and specific demands, often prioritizing certain services offered by care facilities. The second group, however, may not have clearly defined demands and instead seek care facilities with strong overall capabilities. Therefore, two recommendation methods are established in this study.

Recommendation Method for Older People with Clear Demands

Step 1Calculate the subjective weights of criteria (variables). Symbols reflect the presence status and significance of attributes within paths. The original coverage indicates the importance of each path in the configuration. Therefore, multiplying them together and performing the following operations can reveal the weight of attributes in the configuration. Let be the score of the variable in Table 1 for the path and be the raw coverage of the path. Then the subjective weight of the criterion can be obtained by according to the configuration analysis results.

Step 2Get the similarity matrix. This step measures the consistency of expert opinions by calculating similarity between their PLTSs. Let and be PLTSs of the criterion corresponding to experts and for the facility , then the similarity measure between and is defined as Equation 1.where . Then the similarity matrix can be obtained.

Step 3Obtain the weights of experts according to Equation 2. Expert weights are derived based on their consistency, where more consistent experts receive higher weights. Sum of each row of the similarity matrix is denoted as . According to the above definitions, the weight of the expert is expressed as

Step 4Get the entropy measure, and the objective weights of criteria. Entropy for each criterion is calculated to measure assessment uncertainty, where higher entropy indicates greater importance in differentiating facility performance. Let be PLTS of the criterion corresponding to the expert for the facility , then the entropy measure for is defined as Equation 3.where . Then the objective weight of the criterion can be obtained by Equation 4.

Step 5Calculate the comprehensive weights of criteria. This step maximizes the divergence of assessed facility values to identify key discriminating criteria for weighting. The evaluation matrix can be defined as , , and . Next, with the goal of maximizing the deviation of facilities’ assessed values, the following programming model is constructed, see Equation 5. And the comprehensive weight of the criterion can be obtained by solving it.where , and is the assessed value of the facility .

Step 6Calculate the score values of facilities. Facility performance for each criterion is quantified using the concept of dominance, where positive scores indicate superior performance. The dominance degree of each facility over the facility with respect to the criterion is defined as Equation 6.where . The parameter is the attenuation coefficient in the face of loss, the smaller it is, the higher the degree of loss avoidance. Then the score value of the facility with respect to the criterion can be obtained by .

Recommendation Method for Older People with Non-Clear Demands

The competitive advantage and the potential risk are two key indicators for assessing the performance and prospects of care facilities. Competitive advantage degree is used to evaluate the advantage of facilities relative to competitors. Facilities with a high degree of competitive advantage may perform well in certain key aspects, and are often able to attract more older people. They will maintain a high occupancy rate and gain a good reputation. Potential risk degree is used to assess the potential risks and uncertainties faced by facilities. Potential risks may come from many aspects, including market competition, personnel management, financial problems, etc. A high potential risk may mean more challenges for the facility, which may affect the facility’s profitability and customer satisfaction.

Steps 1–6 are the same as recommendation method for older people with clear demands.

Step 7Obtain the competitive advantage degree and potential risk degree. Competitive advantage and potential risk are calculated using a comparison matrix that captures relative dominance and an uncertainty factor. The overall dominance degree of each facility over the facility can be obtained by . The elements in comparison matrix can be calculated by Equation 7.where . The parameter is the uncertainty factor, the higher the value of it, the higher the degree of influence on competitive advantage and potential risk. The competitive advantage degree and potential risk degree of the facility are defined as the row sum and column sum of the comparison matrix, respectively.

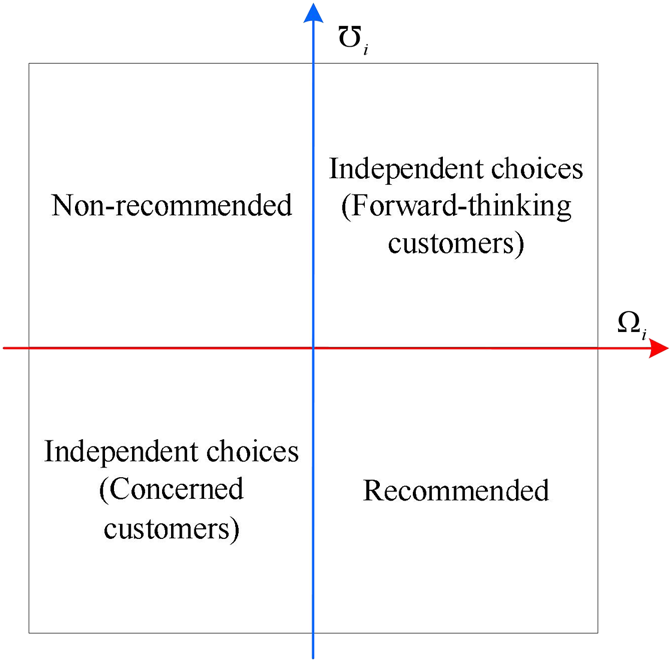

Step 8Draw the positioning of care facilities.In this study, a novel approach is used to provide a new perspective on the selection of care facilities by constructing a coordinate system of competitive advantage degree and potential risk degree. By dividing the four quadrants in the coordinate system, we can position different types of care facilities more clearly and thus provide recommendation strategies for different types of customers. The details can be found in Figure 1. The coordinate point composed of average competitive advantage degree and average potential risk degree is chosen as the origin.The first quadrant represents care facilities with high levels of both competitive advantage and potential risk. Facilities in this quadrant are recommended to forward-thinking customers who are typically open to risk and willing to explore new opportunities and experiences.The second quadrant represents facilities with lower levels of competitive advantage and higher levels of potential risk. In this case, customers are less likely to be advised to choose these facilities. Although there may be some attractive factors, low competitive advantage can affect customers’ experience.In the third quadrant, both competitive advantage and potential risk are lower. These are suitable facilities to recommend to concerned customers who are more focused on stability and avoiding potential risks. While these facilities may lack prominence, they may be better at providing stability and reliable services.The fourth quadrant presents facilities with higher competitive advantage but lower potential risk. In this case, customers are encouraged to prioritize these facilities. This is because these facilities provide satisfactory services while reducing the possibility of exposure to potential risks, allowing customers to achieve a sustained sense of satisfaction.

FIGURE 1

The positioning of different types of care facilities (China, 2023).

Results

In this study, the comprehensive weights of criteria can be obtained as . The score values of facilities can be found in Table 2.

TABLE 2

| 0.6751 | 1.6683 | −1.8618 | −3.7218 | −0.8191 | −4.3252 | |

| −3.9796 | −5.8574 | 0.0706 | −2.3796 | −0.6388 | −4.8671 | |

| −4.9910 | −2.6655 | −11.3013 | −1.0380 | −6.4939 | −2.3315 | |

| −0.3018 | −2.3162 | 1.7691 | −3.4762 | −3.5717 | −5.9636 | |

| 1.1699 | −10.5527 | −6.1940 | 1.1328 | −0.0049 | 1.7785 | |

| 0.1949 | −2.2503 | −1.9104 | −5.2230 | −7.6624 | −3.8080 | |

| −1.2692 | −7.0268 | −6.7460 | −11.2122 | −3.2070 | −0.5920 | |

| −9.0855 | 0.0246 | 0.8943 | −1.7102 | −2.6836 | 0.5424 | |

| −5.9565 | −4.3149 | −7.7865 | 0.1533 | 1.5847 | −5.5668 | |

| −2.0654 | 1.3197 | −5.1390 | 0.5675 | −10.9828 | −1.2610 |

The score values of care facilities (China, 2023).

Therefore, care facilities can be recommended according to the results above. For example, the ranking of medical services is , the care facility is preferentially recommended for older people with clear medical services demands. In addition, older people can choose freely according to the score values under different criteria of care facilities.

To verify the robustness of the methods, different values of the parameter are set to 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1, 1.5, 2, 5, and 10 respectively. The results are shown in Table 3.

TABLE 3

| Criteria | Ranking |

|---|---|

Ranking of care facilities at parameter (China, 2023).

The ranking is constant for different values of the parameter , which fully proves the robustness of the proposed method. It can provide useful information for older people and their family members to choose care facilities.

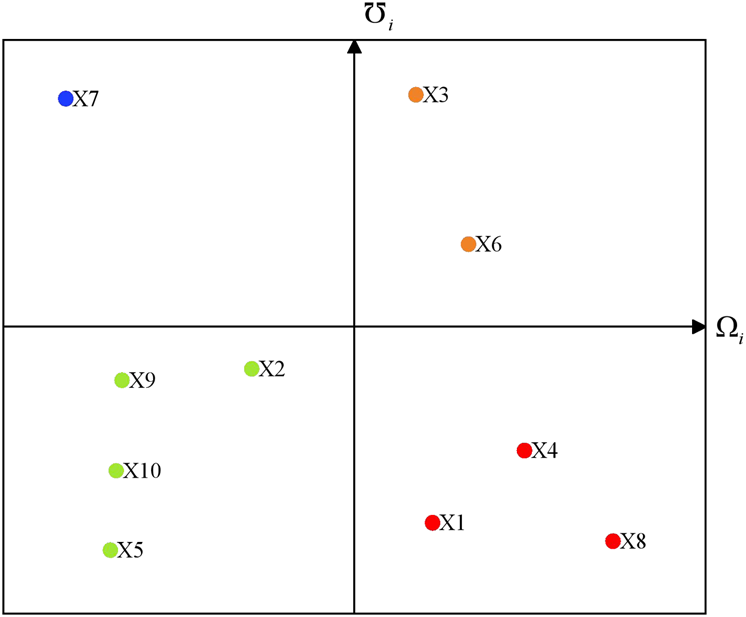

The competitive advantage degree and potential risk degree can be obtained, and the positioning of care facilities can be visually observed in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2

The positioning of care facilities in case study (China, 2023).

Care facilities , , and are preferentially recommend to older people who do not have clear demands. Care facilities and may attract forward-thinking customers. Care facilities , , , and are suitable for concerned customers. However, the care facility is not recommended for older people. We encourage customers to choose a care facility based on their characteristics and actual circumstances.

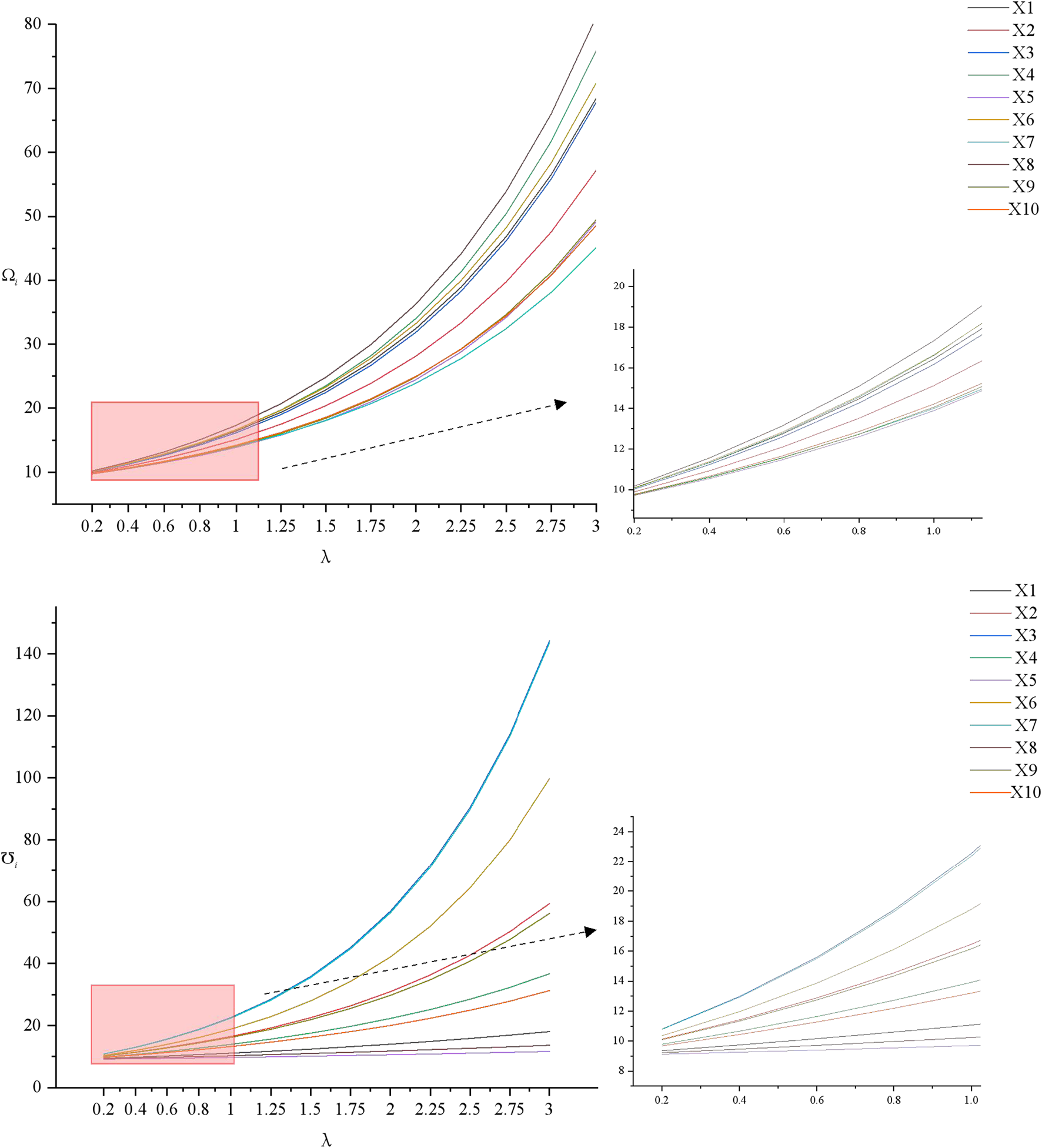

Then the sensitivity of the parameter is analysed to prove the robustness of the second recommendation method. The results are shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3

The sensitivity analysis of parameter (China, 2023).

We can find that with the increase of the parameter , both the difference of competitive advantage degrees and potential risk degrees are gradually obvious. But it basically does not affect the ranking. Hence, the two recommendation methods proposed in this study have good performance.

Discussion

Revelation for the Demands of Older People

This study identified four distinct paths of factors contributing to the high demand for care services, highlighting the diverse demands of older people. These results align with prior studies [15, 39] that have also demonstrated the heterogeneity of care demands among older people. However, our study goes further by pinpointing specific combinations of care services that lead to higher care demands through the application of fsQCA. However, most of the existing studies adopt regression-based methods, focusing on analyzing the isolated effects of individual variables, while ignoring the synergistic effects of variable combinations [40, 41].

The different paths reveal the differences and characteristics among the demands of older people. Path 1 shows that the older people have low demands for nursing services, which implies that they maintain a relatively independent lifestyle without relying heavily on conventional healthcare services. The remaining 3 paths show the demands for medical and nursing services, and there are differences in the demands for other services. Specifically, the older people in Path 2 may have a higher tendency toward extroversion, psychological counseling, and social activities. They expect to gain psychological pleasure and social contact in their later years [42]. Therefore, a range of social activities can be provided by care facilities to satisfy their demands. On the contrary, the older people in Path 3 do not expect much social activity. In addition to satisfactory living and diet conditions, they also demand psychological satisfaction. Their mental health issues should be paid attention to by facilities [43]. Path 4 shows that the older people strongly demand medical and nursing services. They demand more healthcare services and may suffer from chronic diseases or reduced physical mobility.

Overall, these findings reveal a high overall demand for medical services, psychological counselling, and nursing services. This is consistent with studies emphasizing the importance of these services for the wellbeing of older people [44–46]. Diversified demands analysis can help care facilities provide personalized services more responsive to older people. Moreover, such analysis provides policymakers with a valuable reference for developing targeted care service strategies [47]. To effectively address these diverse demands, governments should move beyond a singular focus on medical care and allocate resources toward a more comprehensive and responsive approach. Specifically, policymakers should formulate policies based on the results of demand analysis.

Revelation for Assessment of Care Facilities

This study aims to provide recommendation methods for older people with different demands to choose care facilities. For older people with clear demands, care facilities can be selected according to the first recommendation method. For older people with non-clear demands, facilities can be selected by the second recommendation method. Both methods can meet the various demands of older people and offer more suitable choices for older people. Besides, a greater understanding of demands can help care facilities improve service quality more effectively [48]. Additionally, governments can rationally allocate care services resources and supervise according to evaluation and positioning results to promote the sustainable development of the care industry.

Moreover, the sensitivity analysis shows that our methods are suitable for different situations. Lower indicates that the method is more sensitive to differences between different facilities. Conversely, higher the value of , the more likely it is to highlight the differences in strengths and weaknesses of these facilities. Therefore, setting reasonable values for the parameters can balance the differentiation and fairness of evaluation results. Lower values for parameter and higher values for parameter may enable decision makers to see more clearly the differences of facilities. This also makes it easier for older people to choose and helps optimize resource allocation and service improvements. Otherwise, the difference may be suppressed, affecting the accuracy of the evaluation.

Limitations

There are several limitations in this study. First, the demands of older people surveyed were cross-sectional, which was limited by its self-reported nature. It only selected six types of care services provided by care facilities and might not reflect long-term changes in the demands of older people. Second, this study only included 223 older people and 10 care facilities in Chengdu, China, and the generalizability of the results was limited by geography and sample size. Third, the findings may be influenced by the specific cultural, economic, and social contexts of China. Therefore, there are limitations to the applicability of the results to other regions or countries with different backgrounds. In future research, it is possible to obtain a more diversified demand for older people by expanding the sample and scope of the survey objects. We may also pay attention to the dynamic changes in the quality of care facilities to provide dynamic recommendations for older people.

Conclusion

Through demands analysis, it was found that there were four paths leading to high care services demands of older people. The analysis revealed that medical services, psychological counseling, and nursing services exerted the most significant influence on demand, while diet conditions had the least impact. Furthermore, targeted recommendation methods were provided for older people with different demands, and the robustness of these methods was demonstrated through sensitivity analysis. This study provides valuable insights for older people, care facilities, and governments, enabling them to better address care demands and promote improved living environments.

Statements

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the ethics committee of Sichuan University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: DL and XC; Analysis: KZ and XC; First draft preparation of the manuscript: KZ, DL and XC; Methodology: KZ; Review and editing: KZ and XC. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported in part by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFC3605900), the National Social Science Fund of China (23XSH008), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China (2023SRPA07), and the Innovation Spark Key Project of Sichuan University (2019hhf-05).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.ssph-journal.org/articles/10.3389/ijph.2025.1607249/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Popul Dev Rev (2015) 41(3):555. 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00081.x

2.

Dwolatzky T Brodsky J Azaiza F Clarfield AM Jacobs JM Litwin H . Coming of Age: Health-Care Challenges of an Ageing Population in Israel. Lancet (2017) 389(10088):2542–50. 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)30789-4

3.

Pandey CL . Managing Urban Water Security: Challenges and Prospects in Nepal. Environ Dev Sustain (2021) 23(1):241–57. 10.1007/s10668-019-00577-0

4.

Yu R Leung J Lum CM Auyeung TW Lee JSW Lee R et al A Comparison of Health Expectancies Over 10 Years: Implications for Elderly Service Needs in Hong Kong. Int J Public Health (2019) 64(5):731–42. 10.1007/s00038-019-01240-1

5.

Conway Morris A Kohler K De Corte T Ercole A De Grooth HJ Elbers PWG et al Co-infection and Icu-Acquired Infection in Coivd-19 Icu Patients: A Secondary Analysis of the Unite-Covid Data Set. Crit Care (2022) 26(1):236. 10.1186/s13054-022-04108-8

6.

Poghosyan L Liu J Norful AA . Nurse Practitioners as Primary Care Providers with Their Own Patient Panels and Organizational Structures: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Nurs Stud (2017) 74:1–7. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.05.004

7.

Feng Z Jones K Wang W . An Exploratory Discrete-Time Multilevel Analysis of the Effect of Social Support on the Survival of Elderly People in China. Soc Sci Med (2015) 130:181–9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.02.020

8.

Miyazaki A Okuyama T Mori H Sato K Ichiki M Nouchi R . Drum Communication Program Intervention in Older Adults with Cognitive Impairment and Dementia at Nursing Home: Preliminary Evidence from Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Front Aging Neurosci (2020) 12:142. 10.3389/fnagi.2020.00142

9.

Shie A-J Wu W-F Yang M Wan X Li H . Design and Process Optimization of Combined Medical and Elderly Care Services: An Integrated Service Blueprint–Triz Model. Front Public Health (2022) 10:965443. 10.3389/fpubh.2022.965443

10.

Van der Borg WE Verdonk P Dauwerse L Abma TA . Work-related Change in Residential Elderly Care: Trust, Space and Connectedness. Hum Relat (2017) 70(7):805–35. 10.1177/0018726716684199

11.

Wetzels R Eijken MV Grol R Wensing M Weel CV . Self-management Is Not Related to Lower Demand for Primary Care in Independent-Living Elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc (2010) 53(5):918–9. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53278_8.x

12.

Gu T Li D Li L . The Elderly’s Demand for Community-Based Care Services and its Determinants: A Comparison of the Elderly in the Affordable Housing Community and Commercial Housing Community of China. J Healthc Eng (2020) 2020:1840543. 10.1155/2020/1840543

13.

Mardini MT Iraqi Y Agoulmine N . A Survey of Healthcare Monitoring Systems for Chronically Ill Patients and Elderly. J Med Syst (2019) 43(3):50. 10.1007/s10916-019-1165-0

14.

Steffen P Ommen O Pfaff H . Reduced Patient Demands in Hospitals and Their Determinants. Int J Public Health (2009) 54(1):11–22. 10.1007/s00038-008-7058-5

15.

Li C Wu J Li Y Huang Y . Analysis of Healthcare Needs Differences and Influencing Factors Among Elderly Population: Evidence from Yangtze River Delta Region, China. Front Public Health (2022) 10:949468. 10.3389/fpubh.2022.949468

16.

Subburaman GBB Hariharan L Ravilla TD Ravilla RD Kempen JH . Demand for Tertiary Eye Care Services in Developing Countries. Am J Ophthalmol (2015) 160(4):619–27.e1. 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.06.005

17.

Kobayashi D Goto R Tsugawa Y . Impact of Improved Price Transparency on Patients’ Demand of Healthcare Services. Soc Sci Med (2019) 235:112390. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112390

18.

Horne-Thompson A Khalil H Harding K Kane R Taylor NF . The Impact of Outsourcing Bed-Based Aged Care Services on Quality of Care: A Multisite Observational Study. Int J Qual Health Care (2022) 34(4):mzac092. 10.1093/intqhc/mzac092

19.

Gu T Yuan J Li L Shao Q Zheng C . Demand for Community-Based Care Services and its Influencing Factors Among the Elderly in Affordable Housing Communities: A Case Study in Nanjing City. BMC Health Serv Res (2020) 20(1):241. 10.1186/s12913-020-5067-0

20.

Song S Wang D Zhu W Wang C . Study on the Spatial Configuration of Nursing Homes for the Elderly People in shanghai: Based on Their Choice Preference. Technol Forecast Soc Chang (2020) 152:119859. 10.1016/j.techfore.2019.119859

21.

Wang J Wang Y Cai H Zhang J Pan B Bao G et al Analysis of the Status Quo of the Elderly’s Demands of Medical and Elderly Care Combination in the Underdeveloped Regions of Western China and its Influencing Factors: A Case Study of Lanzhou. BMC Geriatrics (2020) 20(1):338. 10.1186/s12877-020-01616-6

22.

Oud L . Evolving Demand for Critical Care Services for Elderly Adults with Dementia in texas: A Population-Based Study. J Am Geriatr Soc (2016) 64(2):432–4. 10.1111/jgs.13971

23.

Orth J Li Y Simning A Temkin-Greener H . Providing Behavioral Health Services in Nursing Homes Is Difficult: Findings from a National Survey. J Am Geriatr Soc (2019) 67(8):1713–7. 10.1111/jgs.16017

24.

Broad JB Gott M Kim H Boyd M Chen H Connolly MJ . Where Do people die? An international comparison of the percentage of deaths occurring in hospital and residential aged care settings in 45 populations, using published and available statistics. Int J Public Health (2013) 58(2):257–67. 10.1007/s00038-012-0394-5

25.

Arandelovic A Acampora A Federico B Profili F Francesconi P Damiani G . Factors Associated with Hospitalization before the Start of Long-Term Care Among Elderly Disabled People. J Healthc Qual (2019) 41(5):306–16. 10.1097/jhq.0000000000000201

26.

Paul CW . Reconsidering Care for Frail Older People. Can Med Assoc J (2015) 187(10):E311–E312. 10.1503/cmaj.109-5092

27.

Wu C Gao L Chen SL Dong HJ . Care Services for Elderly People with Dementia in Rural China: A Case Study. Bull World Health Organ (2016) 94(3):167–73. 10.2471/blt.15.160929

28.

Park MS Lee SJ Chang SO . Exploring a Nursing Home-specific Interdisciplinary Approach toward Palliative Care for the Demented and Complex-Disabled Elderly. J Hosp Palliat Nurs (2019) 21(6):E9–E15. 10.1097/njh.0000000000000579

29.

Christmann A Van Aelst S . Robust Estimation of Cronbach’s Alpha. J Multivariate Anal (2006) 97(7):1660–74. 10.1016/j.jmva.2005.05.012

30.

Cheung GW Cooper-Thomas HD Lau RS Wang LC . Reporting Reliability, Convergent and Discriminant Validity with Structural Equation Modeling: A Review and Best-Practice Recommendations. Asia Pac J Manag (2024) 41(2):745–83. 10.1007/s10490-023-09871-y

31.

Vis B . The Comparative Advantages of fsQCA and Regression Analysis for Moderately Large-N Analyses. Sociol Methods Res (2012) 41(1):168–98. 10.1177/0049124112442142

32.

Rihoux B Ragin CC . Configurational Comparative Methods: Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and Related Techniques. Sage Publications (2008).

33.

Ragin CC . Redesigning Social Inquiry: Fuzzy Sets and beyond. New York: University of Chicago Press (2008).

34.

Pang Q Wang H Xu Z . Probabilistic Linguistic Linguistic Term Sets in Multi-Attribute Group Decision Making. Inf Sci (2016) 369:128–43. 10.1016/j.ins.2016.06.021

35.

Cheng X Zhang K Wu T Xu Z Gou X . An Opinions-Updating Model for Large-Scale Group Decision-Making Driven by Autonomous Learning. Inf Sci (2024) 662:120238. 10.1016/j.ins.2024.120238

36.

Cheng X Xu Z Gou X . A Large-Scale Group Decision-Making Model Considering Risk Attitudes and Dynamically Changing Roles. Expert Syst Appl (2024) 245:123017. 10.1016/j.eswa.2023.123017

37.

Dong Y Cheng X Xu Z Ma T . Multi-criteria Group Decision-Making Methods with Dynamic Probabilistic Linguistic Information Characterized by Multiple Consecutive Time Points. Int J Mach Learn Cybern (2023) 15:1277–93. 10.1007/s13042-023-01967-7

38.

Dong Y Cheng X Xu Z Chen W Shi H Gong K . Belief Interval Interpretation of Probabilistic Linguistic Term Sets and a Visual Method for Solving the Preference Problem in Multicriteria Group Decision Making. Int J Intell Syst (2021) 36(8):4364–91. 10.1002/int.22463

39.

Enßle F Helbrecht I . Understanding Diversity in Later Life through Images of Old Age. Ageing Soc (2021) 41(10):2396–415. 10.1017/S0144686X20000379

40.

Lu S . The Effects of Neighborhood Variables on Needs of Social Care: A Hierarchical Multiple Regression of Senior Residents in china. J Soc Serv Res (2019) 45(2):241–53. 10.1080/01488376.2018.1480551

41.

Jiang MM Xiao MF Zhang JW Yang MF . Middle-aged and Older People’s Preference for Medical-Elderly Care Integrated Institutions in China: A Discrete Choice Experiment Study. BMC Nurs (2024) 23(1):32. 10.1186/s12912-023-01696-w

42.

Simmonds BAJ Hannam KJ Fox KR Tobias JH . An Exploration of Barriers and Facilitators to Older Adults’ Participation in Higher Impact Physical Activity and Bone Health: A Qualitative Study. Osteoporos Int (2016) 27(3):979–87. 10.1007/s00198-015-3376-7

43.

Wang Y Ye Y Jin Y Chuang Y-C Chien C-W Tung T-H . The Hybrid Multiple-Criteria Decision-Making Model for Home Healthcare Nurses’ Job Satisfaction Evaluation and Improvement. Int J Public Health (2022) 67:1604940. 10.3389/ijph.2022.1604940

44.

Fulmer T Reuben DB Auerbach J Fick DM Galambos C Johnson KS . Actualizing Better Health and Health Care for Older Adults: Commentary Describes Six Vital Directions to Improve the Care and Quality of Life for All Older Americans. Health Aff (2021) 40(2):219–25. 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01470

45.

Mistry SK Ali AM Akther F Yadav UN Harris MF . Exploring Fear of COVID-19 and its Correlates Among Older Adults in Bangladesh. Glob Health (2021) 17:47–9. 10.1186/s12992-021-00698-0

46.

Kalánková D Stolt M Scott PA Papastavrou E Suhonen R , RANCARE COST Action CA15208. Unmet Care Needs of Older People: A Scoping Review. Nurs Ethics (2021) 28(2):149–78. 10.1177/0969733020948112

47.

Song Y Hoben M Norton P Estabrooks CA . Association of Work Environment with Missed and Rushed Care Tasks Among Care Aides in Nursing Homes. JAMA Netw Open (2020) 3(1):e1920092. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20092

48.

Guida C Carpentieri G . Quality of Life in the Urban Environment and Primary Health Services for the Elderly during the Covid-19 Pandemic: An Application to the City of Milan (Italy). Cities (2021) 110:103038. 10.1016/j.cities.2020.103038

Summary

Keywords

demands, older people, care services, healthy aging, recommendation methods, fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis

Citation

Zhang K, Li D and Cheng X (2025) Balancing the Demands of Older People and Care Services of Healthy Aging: Assessment and Positioning of Care Facilities. Int. J. Public Health 70:1607249. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2025.1607249

Received

06 March 2024

Accepted

14 May 2025

Published

30 June 2025

Volume

70 - 2025

Edited by

France Weaver, West Virginia University School of Public Health, United States

Reviewed by

Two reviewers who chose to remain anonymous

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Zhang, Li and Cheng.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaoting Cheng, xt_6110@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.