Commentary Letter

In the past three decades, Ecuador’s health system has faced frequent ministerial turnover, often appointing leaders with limited training in public health policy and management. Although many ministers have strong clinical backgrounds, their lack of public health expertise has hindered a cohesive vision, raising concerns about the leadership’s capacity to tackle the nation’s complex health challenges effectively. The Ministry of Health is responsible for upholding the right to health, promoting health, preventing diseases, overseeing surveillance, and providing integrated care. It also develops clinical protocols and management guidelines, delivers health services, and conducts studies comparing national and international health management best practices [1, 2]. To adequately fulfill these responsibilities, a master’s degree in public health should be the minimum requirement for those considered for the position of Minister of Health. While ministers are indeed supported by technical personnel, they must have enough training to understand technical matters and not be overly reliant on staff or influenced by conflicts of interest [3]. Advanced public health training equips leaders with essential knowledge about financing, management, cost-effectiveness, and health communication, enabling them to evaluate and implement comprehensive health policies [4, 5].

A health minister requires both managerial skills to oversee health services and advocacy skills to ensure that potential effects on population health are integrated into the work of other government departments and ministries [6]. Helath Ministers require strong knowledge of epidemiology and public health preparedness, highlighted by challenges from global health crises like COVID-19. However, the Ministry faces internal issues impacting ministerial effectiveness, including overlapping responsibilities in regulations, unclear accountability, fragmented technical programs, and departments prioritizing specific professions over broader functions [7]. Furthermore, governance within the health sector is heavily influenced by institutional power dynamics. This lack of governance can severely hinder the performance of the Ministry of Health, contributing to systemic failures [8, 9].

Over the past 30 years in Ecuador, most health ministers have lacked advanced degrees or experience in key areas such as public health, epidemiology, or health systems management (see Table 1). This absence of qualifications hinders effective public health leadership, which demands an integrated, evidence-based approach to address social, environmental, and behavioral health determinants [10–13].

TABLE 1

| Name | Gender | Age at the time of assuming the position | Period | Education up to the date of assuming the position of minister of health | Program o project | Appointing government | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edgar Rodas Andrade | Male | 62 years | August 10, 1998 | January 21, 2000 | • Doctor of Medicine and Surgery | The Cotacachi experience of decentralization and the formation of a health council was developed | Jamil Mahuad |

| Fernando Rodrigo Bustamante Riofrío | Male | N/A | January 22, 2000 | January 23, 2001 | • Doctor of Medicine and Surgery • Specialist in Internal Medicinea | Gustavo Noboa | |

| Patricio Jamriska Jácome | Male | N/A | January 23, 2001 | October 1, 2002 | • Doctor of Medicine and Surgery • Specialist in Gynecology and Obstetricsa | ||

| Vicente Antonio Habze Auad | Male | N/A | October 1, 2002 | January 15, 2003 | • Doctor of Medicine and Surgery | ||

| Francisco Xavier Andino Rodríguez | Male | 38 years | January 15, 2003 | August 22, 2003 | • Doctor of Medicine and Surgery • Master’s Degree in Epidemiologya • Specialist in Neurologya | The pentavalent vaccine was introduced into the vaccination schedule. The strategy against malaria was changed to early diagnosis and timely treatment. Treatment of HIV-AIDS with antiretrovirals was started and the program was strengthened together with that of sexually transmitted diseases | Lucio Gutiérrez |

| Ernesto Macario Gutiérrez Vera | Male | 65 years | August 22, 2003 | December 17, 2003 | • Doctor of Medicine and Surgery • Specialist in Clinical Pathologya | ||

| Teófilo Lama Pico | Male | 66 years | December 17, 2003 | April 20, 2005 | • Doctor of Medicine and Surgery | Strengthening of health areas. Development of Universal Health Insurance (AUS). Beginning of the process of decentralization of health to municipalities (Quito, Guayaquil, Cotacachi) | |

| Wellington Sandoval Córdova | Male | 66 years | April 22, 2005 | December 29, 2005 | • Doctor of Medicine and Surgery | Alfredo Palacio | |

| Iván Jacinto Zambrano Cedeño | Male | N/A | December 29, 2005 | May 30, 2006 | • Doctor of Medicine and Surgery | ||

| Guillermo José Wagner Cevallos | Male | N/A | May 30, 2006 | January 15, 2007 | • Doctor of Medicine and Surgery • Higher Diploma of Fourth Level in Local Development and Health • Specialist in Gynecology and Obstetricsa | ||

| Caroline Judith Chang Campos | Female | 46 years | January 15, 2007 | April 21, 2010 | • Doctor of Medicine and Surgery • Specialist in Health Service Management • Master’s degree in health management for Local Developmenta • Doctorate in Health Sciencesa | Implementation of the transformation process of the health sector. Tariff for the exchange of services in the public and complementary network. New Constitution that incorporates health as a right and universal access. Health system based on primary healthcare. Accelerated plan to reduce maternal mortality. Development of the Comprehensive Family and Community Healthcare Model and implementation of basic health teams. 8 new vaccines were incorporated into the Expanded Immunization Program | Rafael Correa |

| David Chiriboga Allnutt | Male | N/A | April 21, 2010 | January 13, 2012 | • Doctor in Medicine and Surgery | ||

| Carina Isabel Vance Mafla | Female | 35 years | August 23, 2012 | November 13, 2015 | • Bachelor of History and Political Science • Master of Public Health | Implement labeling of processed foods | |

| Margarita Beatriz Guevara Alvarado | Female | N/A | November 13, 2015 | January 6, 2017 | • Doctor of Medicine and Surgery • Master of Sexual Educationa | ||

| María Verónica Espinosa Serrano | Female | 34 years | January 6, 2017 | May 24, 2017 | • Medical Doctor • Master of Public Healtha | Implementation of a medical program in the neighborhood | |

| May 24, 2017 | July 3, 2019 | Lenin Moreno | |||||

| Catalina de Lourdes Andramuño Zeballos | Female | N/A | July 3, 2019 | March 21, 2020 | • Doctor of Medicine and Surgery • Specialist in Health Service Management • Master of in Public Health • Doctorate in Public Management and Governancea | ||

| Juan Carlos Zevallos López | Male | 63 years | March 21, 2020 | March 1, 2021 | • Doctor of Medicine and Surgery • Specialization in Cardiology | ||

| Rodolfo Enrique Farfán Jaime | Male | 63 years | March 1, 2021 | March 19, 2021 | • Doctor of Medicine and Surgery • Higher Diploma in Higher Education • Specialist in General Surgery • Master’s Degree in higher Education • Doctor of Educationa | ||

| Mauro Antonio Falconí García | Male | 45 years | March 19, 2021 | April 8, 2021 | • Doctor of Medicine and Surgery • Specialist in Emergency Medicine and Disasters | ||

| Camilo Aurelio Salinas Ochoa | Male | 38 years | April 8, 2021 | May 24, 2021 | • Doctor of Medicine and Surgery • Master’s degree in health management and administration | ||

| Ximena Patricia Garzón Villalba | Female | 51 years | May 24, 2021 | July 7, 2022 | • Doctor of Medicine and Surgery • Doctor of Philosophy Public Health Occupational Health for Health Professionals | Implemented the vaccination against COVID-19 with the coordination of various sectors. Before a ministerial program was a presidential program | Guillermo Lasso |

| José Leonardo Ruales Estupiñan | Male | 65 years | July 7, 2022 | November 23, 2023 | • Doctor of Medicine and Surgery • Specialist in Health Research and Administration | The 10-year health plan was drawn up | |

| Franklin Edmundo Encalada Calero | Male | 49 years | November 23, 2023 | 1 June 14, 2024 | • Doctor of Medicine • Specialist in General Surgery • Master’s Degree in Curriculum Design • Master’s Degree in Health Management and Direction | Daniel Noboa | |

| Manuel Antonio Naranjo Paz y Miño | Male | 69 Years | June 18, 2024 | Current | • Doctor of Medicine • Specialist in Internal Medicine | ||

Description of ministers of the Ministry of Public Health of Ecuador during the 21st century.

Studied during or completed after the MoH appointment.

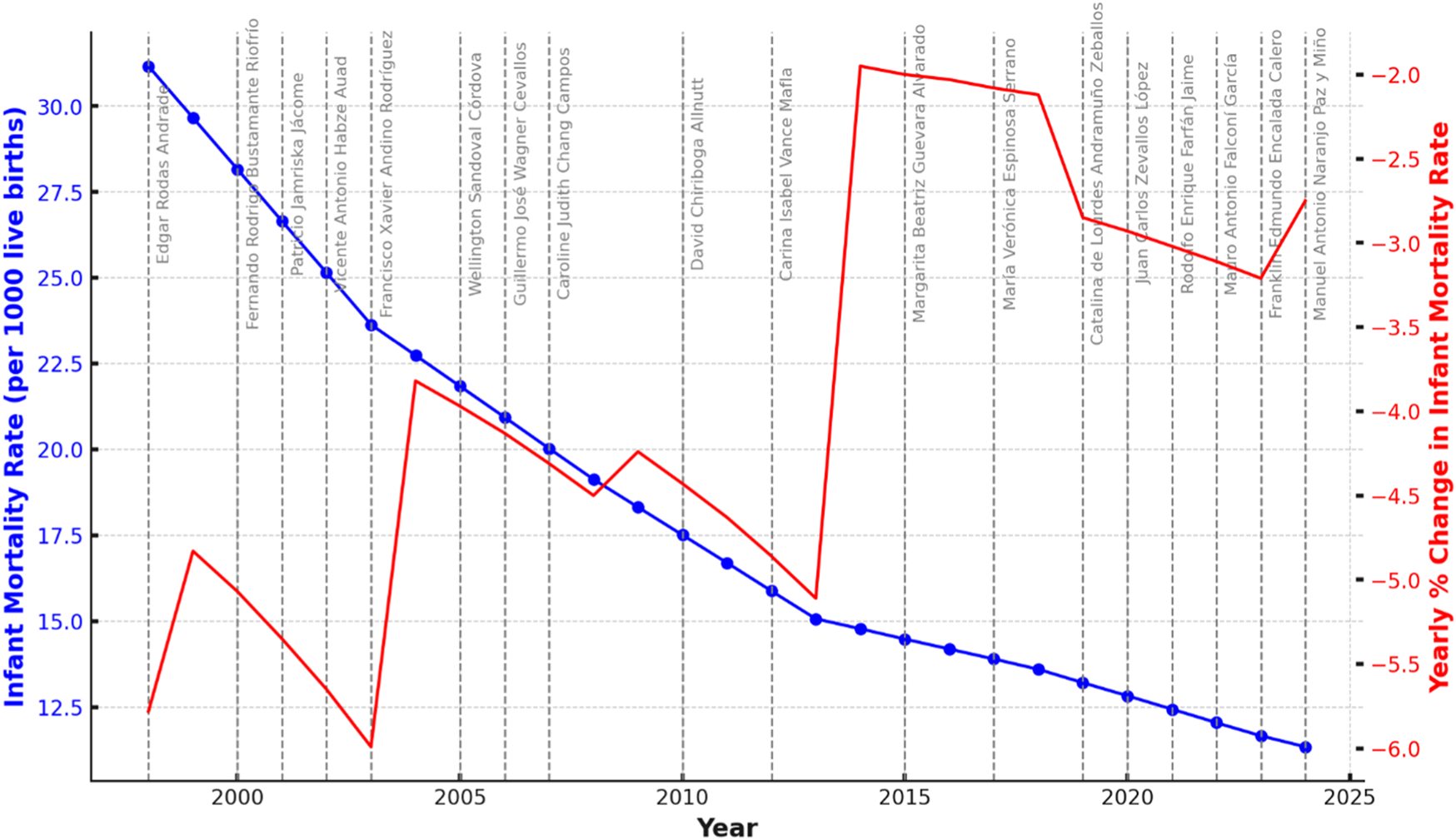

Although the primary role of a health minister is to manage and oversee the national health system, their responsibility also extends to proposing public policies that can be evaluated through tangible improvements in health indicators, such as infant mortality. We believe that this is a significant issue for health governance. Therefore, we conducted an analysis based on the significant reductions in infant mortality during specific periods, identifying the ministers in charge and the outcomes associated with their tenure, highlighting changes that could reflect the impact of effective leadership and policy implementation (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

Trends in Infant Mortality Rate in Ecuador (1998–2024) with Ministerial Terms Highlighted. The blue line represents the infant mortality rate per 1,000 live births, while the red line shows the yearly percentage change in the rate. Gray vertical lines indicate changes in ministerial leadership, with ministers labeled.

Although not much can be inferred from non-causal ecological data, the graph illustrates Ecuador’s infant mortality rate (IMR) from 1998 to 2024, with percentage changes between consecutive years in red. It shows some notable changes. Ministerial changes are marked by vertical dashed lines, with ministers identified by name. There has been a consistent decline in IMR from 31.17 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1998 to 11.345 in 2024, although the rate of decline has slowed in recent years. The most significant decreases occurred between 2000–2005 and 2009–2012. Although the reduction in infant mortality is influenced by many circumstances and determinants typical of a country transitioning from low to middle income, a noticeable slowdown in the decline of the infant mortality rate (IMR) occurred between 2010 and 2020. More recently, (2021–2023) oversaw modest declines in the IMR, despite the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 2).

TABLE 2

| Minister | Period | Start IMR | End IMR | Total change (%) | MPH degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edgar Rodas Andrade | 1998–2000 | 31.170 | 28.159 | −9.65% | No |

| Fernando Rodrigo Bustamante Riofrío | 2000–2001 | 28.159 | 26.653 | −5.35% | No |

| Patricio Jamriska Jácome | 2001–2002 | 26.653 | 25.148 | −5.64% | No |

| Vicente Antonio Habze Auad | 2002–2003 | 25.148 | 23.642 | −5.99% | No |

| Francisco Xavier Andino Rodríguez | 2003–2005 | 23.642 | 21.837 | −7.64% | Yes (MPH) |

| Wellington Sandoval Córdova | 2005–2006 | 21.837 | 20.935 | −4.13% | No |

| Guillermo José Wagner Cevallos | 2006–2007 | 20.935 | 20.032 | −4.32% | No |

| Caroline Judith Chang Campos | 2007–2010 | 20.032 | 17.507 | −12.60% | Yes (MPH) |

| David Chiriboga Allnutt | 2010–2012 | 17.507 | 15.884 | −9.28% | No |

| Carina Isabel Vance Mafla | 2012–2015 | 15.884 | 14.484 | −8.82% | Yes (MPH) |

| Margarita Beatriz Guevara Alvarado | 2015–2017 | 14.484 | 13.895 | −4.07% | Yes (MPH) |

| María Verónica Espinosa Serrano | 2017–2019 | 13.895 | 13.214 | −4.91% | Yes (MPH) |

| Catalina de Lourdes Andramuño | 2019–2020 | 13.214 | 12.827 | −2.93% | Yes (MPH) |

| Juan Carlos Zevallos López | 2020–2021 | 12.827 | 12.440 | −3.02% | No |

| Ximena Patricia Garzón Villalba | 2021–2022 | 12.440 | 12.053 | −3.11% | Yes (MPH) |

| Franklin Edmundo Encalada Calero | 2023–2024 | 11.666 | 11.345 | −2.75% | No |

| Manuel Antonio Naranjo Paz y Miño | 2024-on | 11.345 | N/A | N/A | No |

Ecuadorian ministers of health (1998–2024), infant mortality rates (IMR), and total percentage change in IMR by ministerial tenure.

Bold values in the table represent the largest percentage decrease in Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) during the tenure of a specific Minister of Health, highlighting periods of the most significant improvements in public health outcomes.

In Ecuador, significant milestones in public health were achieved, particularly before the year 2000. Key figures during their tenure led important vaccination campaigns and successfully managed the 1991 cholera outbreak, reducing infant mortality and advancing the Comprehensive Family and Community Health Program [14]. Between 1990 and 2006, the country saw critical reforms, such as the decentralization of health management to municipalities, the formation of Cantonal Health Councils, and the proposal of Universal Health Insurance in 2005–2006 [15]. However, in 2009, these decentralization efforts were reversed with the re-centralization of the health management system [16], undoing much of the progress that had been made.

During 2014, the introduction of new food labeling regulations, which made nutritional information more accessible and positioned Ecuador as a global reference in non-communicable disease prevention was an important contrbution. However, this period was also marked by controversial decisions, including the closure of the National Institute of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the elimination of the National Service for the Eradication of Malaria (SNEM), and the shutdown of vaccine production in Ecuador [17]. Despite these public health initiatives, the reduction in infant mortality rates (IMR) during this period was less pronounced compared to other periods. While some improvements were made, the IMR did not decrease as significantly as might have been expected, highlighting a period where public health outcomes did not fully align with the scale of reforms introduced.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted Ecuador’s severe shortage of public health expertise, resulting in one of the world’s highest excess death rates. Health ministers, often lacking local experience, communication skills, and disease management knowledge, struggled to provide clear public health messaging. This was worsened by significant mismanagement and corruption, including inflated prices for essential medications and supplies, which deepened the crisis [18, 19].

Corruption has long plagued the health sector, with some ministers facing serious allegations. For example, several scandals have involved the procurement of ambulances and other essential supplies at inflated prices, breaching public procurement laws [20–22].

Ecuador’s health leadership has historically been marked by high ministerial turnover, driven by political interests. This instability, coupled with instances of corruption and controversial policies, has hindered effective public health initiatives and created fragmented health policies. While some achievements exist, persistent leadership issues have led to high malnutrition rates and ineffective campaigns on issues like traffic accidents and drug abuse, contrasting sharply with the successes of neighboring countries like Peru.

Appointing leaders focused solely on clinical medicine without a robust public health background poses several risks:

• Fragmented Policies: Lacking public health foundations can lead to ineffective, fragmented policies [13, 23, 24].

• Curative Bias: Overreliance on treatment instead of prevention perpetuates unsustainable healthcare costs [25].

• Insufficient Emergency Preparedness: COVID-19 underscored the need for leaders skilled in epidemiology and crisis management [26–28].

To better manage Ecuador’s health system, technical skills and public health experience should be prioritized over political considerations in minister selection. Ideal candidates would possess:

• Advanced public health qualifications.

• Proven experience in public health policy formulation and evaluation.

• Active public health research engagement.

• Strong leadership and communication skills to articulate a public health vision and make informed, evidence-based decisions.

Recent ministers have lacked communication competencies, resulting in fewer public health campaigns and diminishing the perception of health ministers as public health advocates.

Selecting health ministers is a nuanced task influenced by social, political, and contextual variables, particularly in developing nations like Ecuador. However, the logic and some of the evidence underscores that this process must be approached thoughtfully, prioritizing technical expertise over political considerations, to ensure sustainable public health progress [29–33]. While the public often expects a Minister of Health to be an effective administrator, adept at managing public procurement and addressing operational challenges, what Ecuador urgently requires is a leader with expertise in prevention, health promotion, and ensuring equitable access to healthcare services.

These competencies are often lacking in physicians focused on curative, private-sector roles. This commentary highlights systemic issues, not as a complaint but as a reflection on persistent shortcomings. For example, despite a 25-year national malnutrition prevention program, Ecuador still has one of the region’s highest malnutrition rates. Even during economic booms, investment favored hospital infrastructure over essential primary healthcare. This manuscript urges Ecuadorian authorities to address these issues and adopt the recommended steps for strengthening national health leadership, shifting towards a comprehensive public health focus for sustainable health improvements.

Statements

Author contributions

Conceptualization: EO-P; methodology: EO-P, JI-C, and JV-G; software: JV-G and IS; validation: EO-P, JI-C, and WC; investigation: JI-C, JV-G, and IS; resources: JI-C, JV-G, and IS; data curation: JI-C; writing–original draft preparation: JV-G and IS; writing–review and editing: JI-C and EO-P; visualization: JI-C and EO-P; supervision: EO-P; project administration: JV-G and EO-P; funding acquisition: EO-P. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

1.

Ministerio de Salud Publica. Atribuciones y Responsabilidades – Normatización – Ministerio de Salud Pública (2024). Available from: https://www.salud.gob.ec/atribuciones-y-responsabilidades-normatizacion/(Accessed September 14, 2024).

2.

Ministerio de Salud Publica. Misión, Visión, Principios y Valores – Ministerio de Salud Pública (2024). Available from: https://www.salud.gob.ec/valores-mision-vision-principios-valores/ (Accessed September 14, 2024).

3.

DimoliatisID. A Master of Public Health Must Be the Minimum Prerequisite for a Health Minister: A Timely Proposal to Discuss the Necessary Qualifications of the Ideal Health Minister. J Epidemiol Community Health (2003) 57:755. 10.1136/jech.57.9.755

4.

Ministerio de Salud Publica. Maestría en Salud Pública – Región Xalapa – Ministerio de Salud Pública. Ministerio de Salud Publica (2024). Available from: https://www.salud.gob.ec/maestria-en-salud-publica-region-xalapa/ (Accessed September 14, 2024).

5.

TachéS. The Master's in Public Health: A Better Preparation for Understanding the Health Care System. West J Med (2001) 175:59. 10.1136/ewjm.175.1.59

6.

PearceN. The Ideal Minister of (Public) Health. J Epidemiol Community Health (2002) 56:888–9. 10.1136/jech.56.12.888-a

7.

JeppssonAÖstergrenP-OHagströmB. Restructuring a Ministry of Health – An Issue of Structure and Process: A Case Study From Uganda. Health Policy Plan (2003) 18:68–73. 10.1093/heapol/18.1.68

8.

BermanPAzharAOsbornEJ. Towards Universal Health Coverage: Governance and Organisational Change in Ministries of Health. BMJ Glob Health (2019) 4:e001735. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001735

9.

SheikhKSriramVRouffyBLaneBSoucatABigdeliM. Governance Roles and Capacities of Ministries of Health: A Multidimensional Framework. Int J Health Policy Manag (2020) 10:237–43. 10.34172/ijhpm.2020.39

10.

EdgrenL. The Meaning of Integrated Care: A Systems Approach. Int J Integr Care (2008) 8:e68. 10.5334/ijic.293

11.

GoniewiczKCarlströmEHertelendyAJBurkleFMGoniewiczMLasotaDet alIntegrated Healthcare and the Dilemma of Public Health Emergencies. Sustainability (2021) 13:4517. 10.3390/su13084517

12.

KaplanGBo-LinnGCarayonPPronovostPRouseWReidPet alBringing a Systems Approach to Health. NAM Perspect (2013) 3. 10.31478/201307a

13.

MooreSMawjiAShiellANoseworthyT. Public Health Preparedness: A Systems‐Level Approach. J Epidemiol Community Health (2007) 61:282–6. 10.1136/jech.2004.030783

14.

Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Boletin Epidemiologico - Situacion del Colera en el Ecaudor. OPS (1991) 12:1–24.

15.

GoldmanML. La Descentralización del Sistema de Salud del Ecuador: Un Estudio Comparativo de “Espacio de Decisión” y Capacidad Entre Los Sistemas Municipales de Salud de Quito, Guayaquil y Cuenca. FLACSO Ecuad (2009) 1:1–51.

16.

Jiménez BarbosaWGGranda KuffoMLÁvila GuzmánDMCruz DíazLJFlórez ParraJCMejíaLSet alTransformaciones del Sistema de Salud Ecuatoriano. Univ Salud (2017) 19:126. 10.22267/rus.171901.76

17.

Ortiz-PradoEEspínEVásconezJRodríguez-BurneoNKyriakidisNCLópez-CortésA. Vaccine Market and Production Capabilities in the Americas. Trop Dis Trav Med Vaccin (2021) 7:11–21. 10.1186/s40794-021-00135-5

18.

GonzalezMA. IESS y Salud, Agobiados por la Corrupción, Comprarán Juntos Sus Medicinas. Primicias (2020). Available from: https://www.primicias.ec/noticias/politica/iess-msp-compraran-juntos-medicamentos/(Accessed September 14, 2024).

19.

OrtizS. Caso Encuentro Revela la Ruta Opaca Para Comprar Fármacos. Diario Expreso (2024). Available from: https://www.expreso.ec/actualidad/caso-encuentro-revela-ruta-opaca-comprar-farmacos-209136.html (Accessed September 14, 2024).

20.

ElDGrupoESA. Fiscalía de Ecuador Imputa a Ministra de Salud Por Sobreprecio En Ambulancias. El Diario Ecuador (2009). Available from: https://www.eldiario.ec/noticias-manabi-ecuador/137733-fiscalia-de-ecuador-imputa-a-ministra-de-salud-por-sobreprecio-en-ambulancias/ (Accessed September 14, 2024).

21.

PobleteJC. Viteri Compareció Ayer en el Caso Ambulancias. El Comercio (2009). Available from: https://www.elcomercio.com/actualidad/viteri-comparecio-ayer-caso-ambulancias.html (Accessed September 14, 2024).

22.

TelégrafoE. Ex Ministro de Salud Sentenciado a Tres Años de Prisión. El Telégrafo (2013). Available from: https://www.eltelegrafo.com.ec/noticias/informacion/1/ex-ministro-de-salud-sentenciado-a-tres-anos-de-prision (Accessed September 14, 2024).

23.

SpicerNAgyepongIOttersenTJahnAOomsG. It’s Far Too Complicated’: Why Fragmentation Persists in Global Health. Glob Health (2020) 16:60. 10.1186/s12992-020-00592-1

24.

StangeKC. The Problem of Fragmentation and the Need for Integrative Solutions. Ann Fam Med (2009) 7:100–3. 10.1370/afm.971

25.

CairneyPSt.DennyEBoswellJ. Why Is Health Improvement Policy So Difficult to Secure?Open Res Eur (2022) 2:76. 10.12688/openreseurope.14841.2

26.

KhatriRBEndalamawAErkuDWolkaENigatuFZewdieAet alPreparedness, Impacts, and Responses of Public Health Emergencies Towards Health Security: Qualitative Synthesis of Evidence. Arch Public Health (2023) 81:208. 10.1186/s13690-023-01223-y

27.

OstiTGrisAVCoronaVFVillaniLD'AmbrosioFLomazziMet alPublic Health Leadership in the COVID-19 Era: How Does It Fit? A Scoping Review. BMJ Lead (2024) 8:174–82. 10.1136/leader-2022-000653

28.

Goh Chun ChaoGAnwarKNAhmadMHKunasagranPDBinti MujinSMBujangZet alPublic Health Leadership During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systemic Review. Malays J Med Health Sci (2023) 19.

29.

Ortiz-PradoEFernandez NaranjoRPVasconezESimbaña-RiveraKCorrea-SanchoTListerAet alAnalysis of Excess Mortality Data at Different Altitudes During the COVID-19 Outbreak in Ecuador. High Alt Med Biol (2021) 22:406–16. 10.1089/ham.2021.0070

30.

HayesKTHeimanHJHonoréPA. Developing a Management and Finance Training for Future Public Health Leaders. Front Public Health (2023) 11:1125155. 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1125155

31.

KrukMEGageADArsenaultCJordanKLeslieHHRoder-DeWanSet alHigh-quality Health Systems in the Sustainable Development Goals Era: Time for a Revolution. Lancet Glob Health (2018) 6:e1196–252. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30386-3

32.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Committee on Community-Based Solutions to Promote Health Equity in the United StatesThe Root Causes of Health Inequity. In: WeinsteinJNGellerANegussieYBaciuA. Editors: Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity. National Academies Press US (2017). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK425845/ (Accessed July 3, 2024).

33.

ClarkECBurnettTBlairRTraynorRLHagermanLDobbinsM. Strategies to Implement Evidence-Informed Decision Making at the Organizational Level: A Rapid Systematic Review. BMC Health Serv Res (2024) 24:405. 10.1186/s12913-024-10841-3

Summary

Keywords

public health leadership, health policy, health system, infant mortality, Ecuador

Citation

Ortiz-Prado E, Suárez Sangucho IA, Cañizares Fuentes WR, Vasconez-Gonzalez J and Izquierdo-Condoy JS (2025) The Imperative of Public Health Expertise in Ecuadorian Health Leadership: A Call for Competency-Based Appointments. Int J Public Health 69:1607894. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2024.1607894

Received

24 August 2024

Accepted

20 December 2024

Published

07 January 2025

Volume

69 - 2024

Edited by

Lyda Osorio, University of the Valley, Colombia

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Ortiz-Prado, Suárez Sangucho, Cañizares Fuentes, Vasconez-Gonzalez and Izquierdo-Condoy.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Esteban Ortiz-Prado, e.ortizprado@gmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.