Abstract

Objectives: Implementing public health measures is necessary to decrease sugars intake, which is associated with increased risk of noncommunicable diseases. Our scoping review aimed to identify the types of measures implemented and evaluated to decrease sugars intake in the population and to assess their impact.

Methods: Following a review of systematic reviews (SRs) published in 2018, we systematically searched new SR (May 2017–October 2020) in electronic databases. We also searched the measures implemented in Europe in the NOURISHING database. Two researchers selected the reviews, extracted and analysed the data.

Results: We included 15 SRs assessing economic tools (n = 5), product reformulation and labels/claims (n = 5), and educational/environmental interventions (n = 7). Economic tools, product reformulation and environmental measures were effective to reduce sugar intake or weight outcomes, while labels, education and interventions combining educational and environmental measures found mixed effects. The most frequently implemented measures in Europe were public awareness, nutritional education, and labels.

Conclusion: Among measures to reduce sugar intake in the population, economic tools, product reformulation, and environmental interventions were the most effective, but not the more frequently implemented in Europe.

Introduction

The frequent consumption of excessive dietary sugars, especially sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) is a risk factor for unbalanced diet, weight gain, and an increased risk of noncommunicable diseases including type 2 diabetes [1, 2], cardiovascular disease mortality [3], and dental caries [4, 5]. A causal link between a high-sugar diet and obesity has been found and explained by free sugars, especially in liquid form [5, 6]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the term “free sugars” includes all “monosaccharides and disaccharides added to foods by the manufacturer, cook or consumer, and sugars naturally present in honey, syrups, fruit juices and fruit juice concentrates” [5].

The WHO strongly recommend that intake of free sugars should not exceed 10% of total energy intake, and a conditional recommendation states that it should not exceed 5% [5]. This represents a maximum intake of 50 g/day, ideally 25 g/day, for a person consuming 2,000 calories. In a review comparing total sugars (naturally present and added in food and drink) in several European countries, the mean intake ranged from 76 g/day in Spain to 117 g/day in the Netherlands [7]. In a Swiss survey, the mean intake of total sugars reached 107 g/day (11% of total energy intake), and only 8% of the population followed the WHO recommendation of less than 5% of total energy intake [8].

Many scientific organizations and authorities at international, national and local levels have issued policy recommendations that aim to reduce sugars intake, with a focus on children given their inclination to have higher sugar intake [9]. These include a range of public health measures, such as consumer education, food and nutrition labelling, regulation of the marketing, fiscal policies, population intake monitoring and product reformulation [2]. Governments around the world have already adopted different measures to reduce sugar intake, and their level of implementation differs among the countries, as shown by the NOURISHING database, a tool developed by the World Cancer Research Fund International that indexes by country the measures designed to tackle unhealthy diets [10, 11].

In 2018, a review of reviews published by Kirkpatrick et al. assessed both the impact of measures aiming to decrease sugars intake among populations and the gaps in the available evidence [12]. Based on 12 systematic reviews (SRs) published between 2006 and 2016, the authors concluded that some interventions had the potential to reduce the intake of SSBs including taxes, modification of food environments, and, lastly health promotion and education. However, the limited available evidence and a high heterogeneity of methods and measures in included studies prevented the authors from drawing firm conclusions about the effectiveness of the interventions. Since 2016, numerous studies and reviews have significantly grown the body of evidence on this topic.

Considering the recent literature and the different approaches implemented by countries to reduce sugar intake in the population, it was important to conduct a scoping review that aimed to gather and analyse evidence on this topic, by assessing which measures have been scientifically evaluated, what were their impact, and which measured have already been implemented in Europe. This would help the decision-makers of European countries to identify which measures are preferable. The primary objective of our scoping review was to determine the types of measures studied to decrease sugars intake in the population and their impact. The secondary objective was to identify the measures implemented in Europe.

Methods

Type of Research Conducted

We conducted a scoping review in two steps. Firstly, we searched the SRs that assessed the impact of the measures implemented to reduce sugar intake in the population. The review of reviews of Kirkpatrick et al. also addressed this research question, based on SRs published until 2016. Thus, we focused on SRs published after this date and used a similar research methodology. The main findings of Kirkpatrick et al. were included in our analysis and compared to the more recent data. In addition, we searched the NOURISHING database in order to compile the measures that have been implemented by European countries [11].

Initially, our research group was commissioned by the Swiss Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office FSVO to write a scientific report providing an overview of the strategic options for reducing sugar consumption in Switzerland at the population level [13]. This previous report used international scientific data, but focused on Switzerland. Therefore, the scoping of the current review was expanded to Europe.

A research protocol was developed before this scoping review was conducted, but it was not published. We planned initially to search SRs published until the end of 2019, however as new SRs were published, we extended the publication data and updated the search in October 2020. The PRISMA checklists can be found in Supplementary File S1.

Search of SRs on the Impact of the Measures Implemented to Reduce Sugar Intake

Research Question

Our research question was as follows: “What is the impact of public health measures to reduce sugar consumption on sugar intake and health outcomes in the population?”.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Publications were eligible for inclusion in this review if they were SRs published in English, French, German, or Spanish. Kirkpatrick et al. searched SRs published in English from January 2005 to May 2017 [12]. Therefore, we searched for SRs published between May 2017 and October 2020. Reviews that did not report a systematic search strategy to identify the literature were excluded, but SRs that did not include a meta-analysis were eligible.

We considered the pediatric and adult populations. The interventions included all type of interventions that aimed to support reductions in sugar consumptions among populations, at various levels (e.g., regional, national, and global). These include different study designs such as randomized control trials, nonrandomized controlled trials, pre-post studies, modelling studies, laboratory studies, etc. When the intervention did not aim to decrease specifically sugar intake, i.e., a program to prevent obesity, the SR was excluded. The outcomes could be either sugar intake, SSB consumption and/or any health outcomes.

Search Strategies and Identification of SRs

The search strategy for Medline PubMed used by Kirkpatrick et al. was used to identify recent studies. The full search strategy, checked by an experienced librarian, including all identified keywords and MeSH terms, is presented in Supplementary File S2. In the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, we used the general term “Sugar” and restricted the search to May 2017–October 2020.

To identify eligible studies in the electronic databases, two independent reviewers (SBDT/CJC) screened the titles and abstracts. They assessed the full text of selected citations in detail against the inclusion criteria and recorded the reasons for exclusion. Disagreements that arose between the reviewers were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (CM). Additional eligible studies were searched for in the references of retrieved articles. The results of the search and the study inclusion process were reported in a Prisma flowchart [14].

Extraction of Data and Presentation of Findings

The reviewers developed a data extraction tool to extract data of included SRs including goal, context, study methods, methodological quality appraisal, and key findings relevant to the review question. They were summarized in a table and described narratively.

To categorize the measures used to reduce sugar consumption, we employed categories based on those of Kirkpatrick et al. (“interventions influencing price,” “interventions influencing changes to the food environment,” and “health promotion and education interventions”), and the NOURISHING framework. This latter formalizes possible policies to promote a healthy diet across three domains (food environment, food system, and behavior change communication), and 10 sub-policies areas represented by the letters of the word NOURISHING [10], shown in Supplementary File S3.

We defined the following categories: 1) economic tools including taxes, 2) product reformulation and labels, and 3) education/healthy food environment [12]. The first category corresponds to the “intervention influencing price” of Kirkpatrick et al. and to the letter U of NOURISHING. For the second category, we have combined the different measures from the food environment domain of NOURISHING (letters I and N) other than economic tools, and that we consider applicable at a macro-level (regional or national level). No findings were available for letters R and S. Our last category combines the measures that aim to offer healthy food in specific settings (letter O of “the food environment” domain) and information and education measures (letters I and G of the “behavior change communication” domain). This combination, from two different domains, may seem counter-intuitive as these interventions are expected to impact sugar intake via different pathways. However, as widely recommended, these two types of measures were combined in the large majority of SRs that we included in our scoping review. When feasible, the findings of the SRs were further separated depending on the type of measure.

Search of Measures Implemented in European Countries in the NOURISHING Database

We searched all measures implemented in European countries that aimed to decrease sugars intake among populations in the NOURISHING database (last search conducted in October 2020) [11]. We focused on Europe in order to provide a clear overview of the measures implemented in this world region instead of providing unmanageable data for all countries across the world. We synthesized the results in a table using the NOURISHING framework [10].

Results

Characteristics of Included Studies

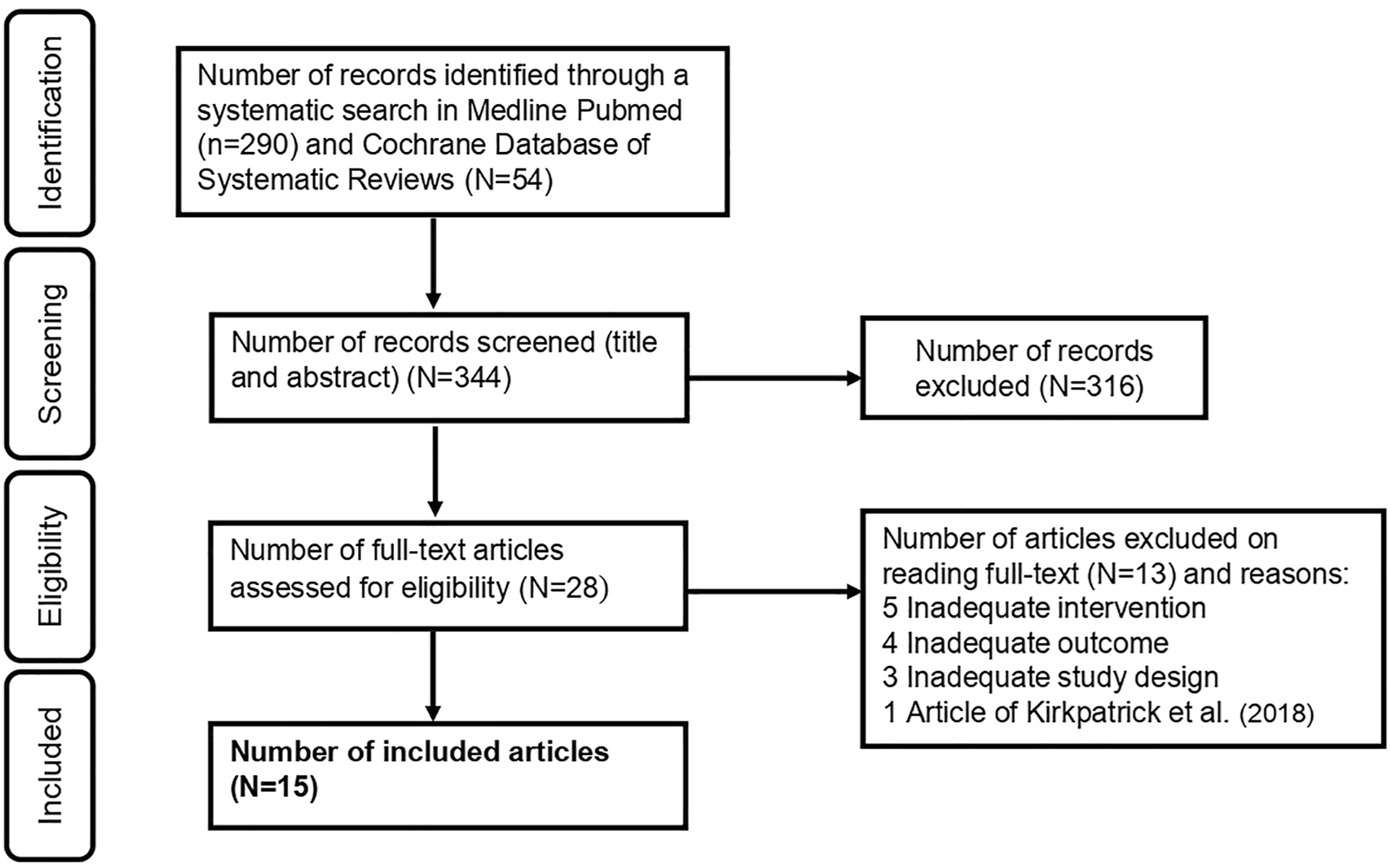

After screening 292 titles and abstracts, and reading 53 full texts, we have included a total of 15 SRs in the current review, as described in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1

Prisma figure showing the inclusion and exclusion of systematic reviews (Impact of measures aiming to reduce sugars intake in the general population and their implementation in Europe: a scoping review. Switzerland. 2019–2021).

The 15 SRs included in this scoping review assessed the effect of the following interventions on sugar intake:

1) Economical tools: five SRs addressed this question i.e., two SRs focusing only on SSB [15], one only on foods with added-sugar [16] and two included both [17]. These SRs included studies with different designs, such as laboratory studies, modelling studies, comparison studies, and pre-post implementation.

2) Product reformulation and labels: three SRs assessed the impact of product reformulation [6, 18, 19], and three SRs assessed the impact of labels or claims [6, 20, 21]. Heterogeneous outcomes were studied such as knowledge, purchase intention, purchase/sale, consumption, diet quality, sugar or energy intake and body weight.

3) Education/healthy food environment: Five SRs evaluated the effect of educational and healthy food environmental interventions [22–26] and two SRs studied the impact of healthy food environmental interventions only [6, 27]. In these seven SRs, the settings were varied and included school, home and community, and a clinical setting. The types of interventions included nutrition education, incentivizing healthier options, reducing availability of less healthy options, policy implementation, and providing water.

The authors of the included SRs assessed the quality of the primary studies using different tools, mainly the Cochrane risk-of-bias tools [28, 29]. Two studies did not provide information on quality assessment [24, 30]. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 15 SRs included.

TABLE 1

| Authors and year | Aim of the review | Period covered | Relevant (total) studies (n) | Interventions considered | Study designs considered | Quality appraisal and/or risk of bias | Funding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of the included systematic reviews on economic tools | |||||||

| [16] | To assess the effects of taxation of unprocessed sugar or sugar-added foods in the general population on the consumption of unprocessed sugar or sugar-added foods, the prevalence and incidence of overweight and obesity, and the prevalence and incidence of other diet related health outcomes | Up to October 2019 | 1 (1) | Taxes on or artificial increases of selling prices for unprocessed sugar or food products that contain added sugar | Controlled studies with more than one intervention or control site and interrupted time series studies with at least three data points before and after the intervention | The EPOC-adapted Cochrane “Risk of bias” tool | Scottish Institute for Research in Economics (SIRE) Early Career Engagement Grant |

| GRADE approach | |||||||

| [6] | To assess the effects of environmental interventions (excluding taxation) on the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and sugar-sweetened milk, diet-related anthropometric measures and health outcomes, and on any reported unintended consequences or adverse outcomes | From databases inception to January 24, 2018 | 7 (58) | Economic tools (price increases on SSB, financial incentives to purchase low-calorie beverages, price discounts on low-calorie beverages in community stores) | Comparison before and after economic tools implemented | The EPOC-adapted Cochrane “Risk of bias” tool | No specific grant |

| GRADE approach | |||||||

| [15] | To conduct a systematic review of real-word SSB tax evaluations and examine the overall impact on beverage purchases and dietary intakes by meta-analysis | From database inception to June 2018 | 18 (18) | SSBa taxes | Comparison between pre–post tax (n = 11) or taxed and untaxed jurisdiction(s) (n = 6) | Critical appraisal tool based on 12 study quality criteria | Health Research Council (HRC) of New Zealand and the BODE3 Program |

| [17] | To examine research evidence on the health and behavioral impacts of fiscal measures targeted at high sugar foods and SSBs in both adult and children populations | 2010 - October 2014 | 11 (11) | High sugar foods and SSBsa taxes | Laboratory (n = 4), virtual setting (n = 4), controlled field experiments in supermarkets (n = 2) or a cafeteria (n = 1) | Joanna Briggs Institute appraisal tools | Public Health England (PHE) |

| [30] | To determine how health taxes can be designed to reduce consumption of targeted products and related health harms (and two other aims non-related to our question) | 1990 - May 2016 | 49 (102) | Health taxes that target unhealthy products, including SSBa | Modelling studies (n = 54); experiments (n = 10), public opinion surveys (n = 9), qualitative approaches (n = 11) and mixed methods (n = 2) | Not stated | Cancer Research UK and Phillip Leverhulme Prize award |

| Characteristics of the included systematic reviews on product reformulation and labels | |||||||

| [6] | To assess the effects of environmental interventions (excluding taxation) on the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and sugar-sweetened milk, diet-related anthropometric measures and health outcomes, and on any reported unintended consequences or adverse outcomes | From databases inception to January 24, 2018 | 11 (58) | Labelling and whole food supply | Comparison before and after labelling and whole food supply interventions implemented | The EPOC-adapted Cochrane ‘Risk of bias’ tool | No specific grant |

| GRADE approach | |||||||

| [20] | To summarize the evidence for the association between use of food labels and dietary intake | 1995–2016 | 36 (36) | general food labels, nutrition facts panel, serving sizes, ingredients list, front-of-pack labels, health-related claims | 20 cross-sectional, 1 cohort, 5 RCTsb | Academy of Nutrition and Dietetic Quality Criteria Checklist | No specific grant |

| [18] | To determine the effect of product reformulation measures on sugar intake and health outcomes | 1990 to early 2016 | 16 (16) | Product reformulation | 4 RCTsb, 6 modeling studies, 5 simulation studies, and 1 mix study | The Cochrane risk-of-bias tools | No specific grant |

| [21] | To assess the influence of nutrition claims relating to fat, sugar, and energy content on product packaging on several aspects of food choices to understand how they contribute to the prevention of overweight and obesity | January 2003 to April 2018 | 2 (11) | Nutrition claims related to sugar content (1 study on cereal and 1 study on yogurt) | Experimental setting | Effective Public Health Practice Project’s Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies | No specific grant for this research |

| [19] | To undertake a systematic review of simulation studies that model dietary strategies aiming to improve nutritional intake, body weight, and related chronic disease, and to assess the methodologic and reporting quality of these models | From database inception to July 2016 | 2 (45) | Product reformulation | Modeling studies | Methodology and reporting quality critiqued with a set of quality criteria adapted from generic modeling guidelines | National Health and Medical Research Council Program Grant (631947). Early Career Fellowship (1053359) |

| Characteristics of the included systematic reviews on education/environmental interventions | |||||||

| [22] | To examine whether the promotion of water intake could reduce sugar sweetened beverage (SSBa) consumption or purchases independent of interventions that target SSBsa | January 2000 -January 2019 | 17 (17) | Water provision, education or promotion activities | 9 RCTsb, 6 nonrandomized controlled trials, and 2 single-group pre-post studies | The Cochrane Collaborative Risk of Bias 2.0 and Risk Of Bias In Nonrandomized Studies-I tools | Healthy Eating Research, a national program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation |

| [6] | To assess the effects of environmental interventions (excluding taxation) on the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and sugar-sweetened milk, diet-related anthropometric measures and health outcomes, and on any reported unintended consequences or adverse outcomes | From databases inception to January 24, 2018 | 23 (58) | Nutrition standards in public institutions (schools) and home-based | Comparison before and after the implementation of nutrition standards in public institutions (schools) and home-based interventions | The EPOC-adapted Cochrane “Risk of bias” tool | No specific grant |

| Interventions on environment only | GRADE approach | ||||||

| [23] | To explore the effectiveness of educational and behavioral interventions to reduce SSBa intake and to influence health outcomes among children aged 4–16 years | From database inception to September 2016 | 16 (16) | 12 school-based interventions and 4 community or home interventions | 16 RCTsb: 12 school-based interventions and 4 community or home interventions | The Cochrane risk-of-bias tool | University of Balamand, Lebanon and World Health Organization, University of Liverpool, UK |

| [27] | To systematically review and quantify the impact of school food environment policies on dietary habits, adiposity, and metabolic risk in children | From database inception to December 2017 | 8 (8) | School food environment policies targeting food/beverage availability at school | 1 RCTb and 7 non-randomized trials | Assessment of exposure, outcome, control for confounding, and evidence of selection bias | NIH, NHLBI |

| Interventions on environment only | |||||||

| [24] | This review aimed to scope the literature documenting SSBa consumption and interventions to reduce SSBa consumption among Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people | From January 1980 to June 2018 | 18 (18) | Intervention that had a specific focus on reducing SSBa consumption: incentivizing healthier options (n = 4), reducing availability of less healthy options (n = 1), nutrition education (n = 5), multifaceted (n = 5) or policy implementation (n = 3) | Interventional studies | No quality assessment | University of South Australia and the NHMRC Program |

| [25] | To evaluate the effectiveness of public health interventions to reduce SSBa intake or increase water intake in children, adolescents and adults. To examine the study characteristics that could bring about change in consumption patterns | 1990–2016 | 50 in total | Education, including in clinical setting (n = 27) | RCTsb | The Cochrane risk-of-bias tools | One author is supported by governmental scholarship |

| 40 in the meta-analysis | Education and delivery of water (n = 5) | cluster RCTsb | |||||

| Education and environmental changes (n = 3) | non-RCTb on community-based interventions with control group | ||||||

| Only delivery or environmental change or a mix (n = 3) | |||||||

| [26] | To verify the efficacy of school-based interventions aimed at reducing SSBa consumption among adolescents in order to develop or improve public health interventions | From database inception to December 2016 | 36 (36) | Educational/behavioral interventions (n = 20) | RCTsb or cluster RCTsb (n = 13) | Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) tool | University of Quebec, Canada |

| Legislative/environmental interventions (n = 10) | Quasi-experimental studies (n = 11) | ||||||

| Intervention targeting both individuals and their environment (n = 6) | One-group pre-post studies (n = 12) | ||||||

Characteristics of the 13 included systematic reviews (Impact of measures aiming to reduce sugars intake in the general population and their implementation in Europe: a scoping review. Switzerland. 2019–2021).

Sugar-sweetened beverages.

Randomized controlled trial.

Impact of the Use of Economic Tools Mainly Health Taxes

Table 2 details the findings of the five SRs that assessed the impact of economic tools on sugar consumption. Pfinder et al. showed that taxing foods exceeding a specific sugar threshold value impacted the consumption of sugar-added foods based on one study [16]: after implementation of the Hungarian public health product tax, the mean consumption of taxed sugar-added foods decreased by 4.0% [95% Confidence interval (CI): −0.07 to −0.01; very low-certainty evidence]. Teng et al., who made comparison between pre–post tax (n = 11) or taxed and untaxed jurisdiction(s) (n = 6), found that a 10% SSB tax was associated with an average decline in beverage purchases and dietary intake of 10.0% (95% CI: −5.0% to −14.7%), with considerable heterogeneity between results between jurisdictions [15]. Meta‐analysis results varied by study design and tax type, but not significantly. No significant difference was observed by study quality, consumption measure, age group (all ages, adults or children), or funding source.

TABLE 2

| Authors, year | N studies and location | Type of interventions | Study population | Mains conclusions regarding effectiveness | Key findings related to offsetting or compensatory behaviors | Main limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evidence on the effect of economic tools | ||||||

| [16] | 1 | Taxes on or artificial increases of selling prices for unprocessed sugar or food products that contain added sugar | Children (0–17 years) and adults (18 years or older) | There was very limited evidence and the certainty of the evidence was very low | The results of this systematic review was derived from one included study, resulting in low evidence | |

| Hungary | The mean consumption of taxed sugar-added foods (measured in units of kg) decreased by 4.0% (95% CI: −0.07 to −0.01) | |||||

| [6] | 7 | Economic tools (price increases on SSBa, financial incentives to purchase low-calorie beverages, price discounts on low-calorie beverages in community stores) | Children, teenagers and adults | Price increases on SSBsa were associated with decreasing SSB sales, but with a moderate-certainty evidence. Based on three studies, SSBa sales decreased by −19% (95% CI −33 to −6) at 4–12 months | Few studies have evaluated the same interventions, so the evidence is low | |

| Mostly United States, but also Australia, the Netherland, Canada, UK and others | Price discounts on low-calorie beverages resulted in mixed effects on SSBa sales | |||||

| [15] | 18 | SSBa taxes | Children and adults | Meta-analysis | A 10% SSBa tax was associated with a nonsignificant 1.9% increase in total untaxed beverage consumption (e.g., water) (95% CI: −2.1 to 6.1%) | Risk that incomplete publications biased results towards a greater decline |

| Mostly US and Europe | A 10% SSBa tax was associated with an average decline in beverage purchases and dietary intake of 10.0% (95% CI: −5.0% to −14.7%), with considerable heterogeneity between results | |||||

| [17] | 11 | High sugar foods and SSBsa taxes | Adults (n = 10) Children 12–14 years (n = 1) | In 10 studies, an increase in the price of high sugar foods and SSBsa resulted in a decrease in purchases, at least in the short term. This reduction may be proportionate to the level of price increase imposed. One study showed no effect | In two studies, subsidies of “healthy” foods lead to an increase in “unhealthy” and/or total calories purchase | Eight studies were conducted in a laboratory or virtual setting which may not reflect real-life situations |

| United States (n = 7), Europe (n = 4) | None of the studies examined the effects of pricing on consumption or longer term health outcomes | |||||

| [30] | 102, mostly US (n = 51) and Europe (n = 34) | SSBa taxes | Children and adults | 18/26 studies found a positive impact of SSBsa taxes on reduction in their consumption | The authors could not apply a uniform method of critical appraisal across studies | |

| High tax on SSBsa (>20% of the initial price) are more likely to have a positive impact on health behaviors and outcomes | ||||||

| Evidence on the effect of product reformulation and labels | ||||||

| [6] | 11 | Labelling and whole food supply | Children, teenagers and adults | Moderate-certainty evidence: traffic-light labelling was associated with decreasing SSBa sales | Few studies have evaluated the same interventions, so the evidence is low | |

| Product reformulation and label/claims | Mostly United States, but also Australia, Netherlands, Canada, UK and others | Low-certainty evidence: nutritional rating score labelling was associated with decreasing sales of SSBsa | ||||

| For menu-board calorie labelling reported effects on SSBa sales varied | ||||||

| Associations between voluntary industry initiatives to improve the whole food supply and SSBa sales varied | ||||||

| [20] | 36 | General food labels, nutrition facts panel, serving sizes, ingredients list, front-of-pack labels, health-related claims | Adults | Food labels: 12/13 studies found positive association with healthier diet quality. One study found a negative association | Health related claims may lead to overconsumption, known as the “health halo” effect | Most studies had neutral ratings on quality checklist |

| Label/claim | Mostly United States (n = 20), but also Europe (n = 4), South Korea (N = 2) and Australia (n = 1) | Nutrition facts panels: 10/12 studies found positive association with a healthier diet. | Limitations of the included studies: non-generalizable demographics, use of observational studies, risk of self-selection bias and social desirability bias | |||

| Ingredients lists, serving size information and front-of-pack labels: insufficient research | ||||||

| Health related claims: unclear whether beneficial or detrimental | ||||||

| [18] | US (n = 7), Canada (n = 1), UK (n = 3) and France (n = 3) | 4 RCTsb, 6 modeling studies, 5 simulation studies, and 1 mix study | Children, teenagers and adults | Results from RCTsb showed that consumption of reformulated products can reduce sugar intake and body weight | Limited number of included studies with high risk of bias and an overall low to very low quality grade | |

| Product reformulation | Meta-analysis: | Limitations of the included studies: inadequacy of dietary intake and food composition data, variation in the interventions | ||||

| Reformulation of products lead to a reduction of −11% (95% CI, −20 to 2) in sugar intake and −1.0 kg (95% CI, −2.2 to −0.1) in body weight | ||||||

| [21] | 2 | Nutrition claims related to sugar content (1 study on cereal and 1 study on yogurt) | Adults | Findings indicated that nutrition claims may have an impact on the knowledge of consumers with respect to perceived healthful- ness, expected and experienced tastiness, and perceived appropriate portion size. Nutrition claims were found to potentially influence food purchase intentions, food purchases and consumption | The findings also indicated the potential for unintended consequences, whereby nutrition claims may lead to overconsumption of foods and subsequent higher energy intakes | Low methodological quality of the included studies |

| Claims | Germany (n = 2) | Results may vary depending of the type of food tested (healthier or unhealthy). Only a few studies measured energy intake | ||||

| [19] | 9 | Simulation studies on reformulation (n = 9): e.g., reformulation of foods to reduce nutrient content | Children and adults (2–69 years old) | Reformulating SSBsa by replacing added sugar with artificial sweetener theoretically reduced energy intake by 107 kcal/d. Reformulating free sugars in SSBsa without the addition of artificial sweeteners at a level of 9.7% per year predicted a 38 kcal/d reduction in energy intake over 5 years | Lack of quality assessment tools specifically designed for dietary simulation modeling studies | |

| Product reformulation | Netherlands (n = 3), UK, Finland, US (n = 2), Australia, New Zealand | Limited external validity due to the design of simulation studies | ||||

| Evidence on the effect of educational/environmental interventions | ||||||

| [22] | 17 | Water provision, education, and promotion activities. 11/17 studies used 2 or more types of interventions | Children ages 2–18 years in 14 studies and adults in three studies | In 7/17 studies, a statistically significant decrease in SSBa consumption/purchase was observed | Only two included studies were at low or some/moderate risk of bias | |

| Europe (n = 8), United States (n = 6), Australia (n = 2), and in the Caribbean (n = 1) | Intervention settings included schools (9), homes (3), supermarkets (2), other child-focused settings such as preschools (2), and community-wide (2) | Studies that included water provision, education or promotion, or some combination reported decreased SSBa intake more often than water price discounting and community intervention studies, which had no effects | A large heterogeneity was observed in the measurement of SSBa intake | |||

| [6] | 11 | Nutrition standards in public institutions (schools) and home-based | Children, teenagers and adults | Low-certainty evidence: reduced availability of SSBsa in schools was associated with decreased SSB consumption | Few studies have evaluated the same interventions, so the evidence is moderate-low | |

| Interventions on environment only | Mostly United States, but also Australia, the Netherland, Canada, UK and others | Low-certainty evidence: improved availability of drinking water in schools and school fruit programs were associated with decreased SSBa consumption. Reported associations between improved availability of drinking water in schools and student body weight varied | ||||

| Improved availability of low-calorie beverages in the home environment was associated with decreased SSBa intake (by –413 ml/day, 95% CI –684 to –143 at 4–12 months, moderate-certainty evidence) and with decreased body weight among adolescents with overweight or obesity and a high baseline consumption of SSBsa (high-certainty evidence) | ||||||

| [24] | 18 | Intervention aiming to reduce SSBa intake: incentivizing healthier options (n = 4), reducing availability of less healthy options (n = 1), nutrition education (n = 5), multifaceted (n = 5) or policy implementation (n = 3) | Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people | The more impactful studies seemed to be those which were community driven or involved extensive community consultation and collaboration | An appraisal of quality of included study was not performed | |

| Remote communities (n = 13), rural communities (n = 1), South East Queensland (n = 2) and Victoria (n = 2) in Australia | Findings from the effect of educational-interventional programs were controversial | |||||

| [27] | North America: US (n = 7), Canada (n = 1) | Competitive food/beverage standard provided at school: product-specific restrictions; standards on nutrients, calories, or portion sizes; or both | Children in primary, secondary and preschools | Meta-analysis: Competitive food/beverage standards reduced habitual intake SSBsa by 0.18 servings/day (95% CI: −0.31, −0.05) and unhealthy snacks by 0.17 servings/day. SSB in-school intake decreased by −0.02 servings/d (n = 5), but it was not significant (95% CI: −0.04, 0.01) | No effect on total calories was observed | Some studies were judged to have lower quality scores |

| Interventions on environment only | Several studies included other intervention components that might contribute to impact | |||||

| [23] | 16 | 12 school-based interventions and 4 community or home interventions | Children aged 4–16 years | Overall, educational and behavioral interventions, when compared with no intervention, were found to be successful in reducing SSBa intake among children and adolescents | 13/16 eligible trials (= 17′555 participants) could not be included in the meta-analysis because of the variability in scales used to report the outcomes of interest | |

| Mostly Europe (n = 10) and US (n = 4) | Meta-analysis (n = 3): | |||||

| School-based interventions were associated with a trend toward reduction in SSBa intake compared with no intervention (−284 ml; 95% CI, −643 to 76) | ||||||

| Body mass index z scores did not change significantly | ||||||

| [25] | 50 studies from United States, Europe, South America, Australia, Canada, Malaysia, New Zealand | Education, including in clinical setting (n = 27) | Children, adolescents and adults | Meta-analysis (n = 40): | Among behavior change techniques used, the technique “model/demonstrate the behavior” was associated with the greater effectiveness to reduce SSBa across all age groups | Risk of bias across the 40 studies meta-analyzed was generally medium to high |

| Education and delivery of water (n = 5) | Interventions significantly decreased consumption of SSBa in children by 76 ml per day [95% confidence interval (CI) −105 to −46; 23 studies, p < 0.01], and in adolescents (−66 ml per day, 95% CI −130 to −2; 5 studies, p = 0.04) but not in adults (−13 ml per day, 95% CI −44 to 18; 12 studies, p = 0.16) | |||||

| Education and environmental changes (n = 3) | For children, there was evidence to suggest that modelling/demonstrating the behavior helped to reduce SSBa intake and that interventions within the home environment had greater effects than school-based interventions | |||||

| Only delivery or environmental change or a mix (n = 3) | ||||||

| [26] | United States and Canada (n = 27), Europe (n = 3), Australia (n = 2), Brazil (n = 1), Asia (n = 3) | Educational/behavioral interventions (n = 20) | Adolescents (12–17 years old) | Over 70% of all interventions, targeting individuals, their environment or both, were effective in decreasing SSBa consumption. The success rates were 90% for legislative/environmental approaches; 65% for educational/behavioral interventions; and 67% for a combination of educational/behavioral and legislative/environmental approaches | Two studies reported significant increases in SSBa consumption post-intervention | Large heterogeneity between studies, preventing from conducting a meta-analysis |

| Legislative/environmental interventions (n = 10) | ||||||

| Intervention targeting both individuals and their environment (n = 6) | ||||||

Overview of evidence on the effect of economic tools, product reformulation and labels, and educational/environmental interventions (Impact of measures aiming to reduce sugars intake in the general population and their implementation in Europe: a scoping review. Switzerland. 2019–2021).

Sugar-sweetened beverages.

Randomized controlled trial.

Von Philipsborn et al. demonstrated, based on three studies, that an increased SSB price was associated with a reduction in SSBs sales by −19% (95% CI: −33 to −6%) at 4–12 months [6]. Roberts et al. found in 10/11 studies a decrease in purchases of SSBs and high sugar foods, at least in the short term, following an increase in prices [17]. Wright et al. observed in 18/26 studies a positive impact of SSB taxes on the reduction of their consumption. The observed effect may be proportionate to the level of the tax. Tax on SSBs higher than 20% of the initial price appeared more likely to have a positive impact [30].

Impact of the Use of Product Reformulation or Labels/Claims

The two SRs of Hashem et al. and Grieger et al. assessing the impact of reformulation essentially included modelling and simulation studies (Table 2) [18, 19]. They showed a theoretical reduction in sugar consumption and an estimated improvement in health outcomes. In addition, Hashem et al. observed, based on four randomized controlled trials assessing the effect of sugar-reformulated products over a period of 8–10 weeks, a reduction of −11% (95% CI, −20 to 2) in sugar intake and −1.0 kg (95% CI, −2.2 to −0.08) in body weight [18]. In the SR of von Philipsborn et al., very low-certainty evidence from three studies suggested that voluntary industry initiatives to improve the nutritional quality of the whole food supply may affect SSB sales and purchases, but the direction of reported effects varied [6].

Regarding the use of food labels, the SR of von Philipsborn et al. found moderate-certainty evidence that traffic-light labelling was associated with decreasing sales of SSBs, and low-certainty evidence that nutritional rating score labelling was associated with decreasing sales of SSBs [6]. Anastasiou et al. found a positive association between food labels and healthier diet quality in 12/13 studies, and one study found a negative association. In addition, the authors observed a positive association between the use of nutrition fact panels and a healthier diet in 10/12 studies. Research on the effect of the use of ingredient lists, serving size information and front-of-pack labels was insufficient to draw conclusions [20].

In the two SRs of Oostenbach et al. and Anastasiou et al., it remains unclear whether the impact of food health-related claims was beneficial or detrimental [20, 21].

Impact of the Educational and Healthy Food Environmental Interventions

As stated previously, the seven SRs assessing the impact of educational/healthy food environmental interventions included very heterogenous study designs, interventions, settings, and populations. Except the SR of Micha et al. focusing on SSB and snacks, the other SRs evaluated only SSB intake, as illustrated in Table 2.

The majority of those reviews observed a reduction in sugar intake, mostly assessed by a reduction in SSB consumption. The SRs of Micha et al. [27] and von Philipsborn al et. [6], which studied the impact of healthy food environmental interventions only, and not education, showed beneficial impact on SSB intake, and unhealthy snacks intake or weight. More specifically, in a meta-analysis including 5/11 studies, von Philipsborn et al. reported a decrease in SSB consumption of −413 ml/day (95% CI: −684 to −143) after 4–12 months, when improving access to low-calorie beverages in the home environment among high consumers of SSBs at baseline. The same SR also concluded that a reduced availability of SSBs in schools was associated with decreased SSB consumption. Based on low evidence, these authors showed that improved availability of drinking water in schools and school fruit programs were associated with decreased SSB consumption [6]. Micha et al. reviewed the impact of school food environmental policies and observed a reduction of 0.18 servings of SSB/day (95% CI: −0.31 to −0.05) compared to habitual intake [27].

The five other included SRs examined the effect of educational and healthy food environmental interventions. In 2020, Dibay Moghadam et al. found a statistically significant decrease in SSB consumption/purchase in 7/17 (41%) studies promoting water consumption [22]. Based on 36 studies, Vézina-Im et al. concluded that over 70% of all interventions targeting individuals, their environment, or both were effective in decreasing SSB intake. The success rates (defined as the proportion of studies showing a significant reduction in SSB consumption) were 90% for legislative/environmental approaches, 65% for educational/behavioral interventions, and 67% for a combination of educational/behavioral and legislative/environmental approaches [26]. These authors found that more than half of the interventions were based on a psychosocial theory. The most frequent behavior-change techniques were: providing information about health consequences, restructuring the physical environment, behavioral goal setting, self-monitoring of behavior, threats to health, and providing general social support [26].

Some SRs provided findings for specific age groups. Abdel Rahman et al. assessed the impact of educational and behavioral interventions among children aged 4–16 years and found a trend toward reduction, with a mean reduction of 284 ml/day (95% CI, −643 to 76) [23]. Vargas-Garcia et al. evaluated the impact of educational and/or environmental changes on different age groups. A significant decrease in SSB intake was observed in children, with a mean reduction of 76 ml/day (95% CI: −105 to −46; 23 studies), and in adolescents, with a mean reduction of 66 ml/day (95% CI: −130 to −2; 5 studies). The reduction in adults was not statistically significant [25].

Comparison With the Previous Findings

A total of 12 SRs were included in the review of Kirkpatrick et al. [12], assessing the effect of price changes (n = 6) [31–36] and food environment interventions (n = 7) [34, 37–42], and health promotion and education (n = 7). The seven SRs that assessed the effect of food environmental interventions were the same that studied the impact of health promotion/education. The Supplementary File S4 details the characteristics and main findings of the studies included in the review of Kirkpatrick et al., as presented by these authors.

As illustrated in Table 3, Kirkpatrick et al. found positive impact of taxes on SSB demand and consumption in four SRs [12]. The findings on taxes and weight changes were less consistent; two reviews found positive outcomes, two found mixed results, and one showed no effect. No SR on the impact of labels/reformulation were included by Kirkpatrick el al. [12]. The five SRs that assessed the impact of environmental interventions alone showed reduction in SSB consumption. The impact of educational measures on SSB consumption was positive in three SRs, mixed in one SR, and no impact was observed in one SR. The impact of the educational/environmental measures on weight was more contrasted (beneficial effects: n = 3; mixed effects: n = 4; and no effect: n = 2).

TABLE 3

| SSBa demand | SSBa consumption | Weight outcomes | Other outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic tools | ||||

| [16] | + (sugar-added foods intake) | |||

| [6] | + | |||

| [15] | + | |||

| [17] | + | |||

| [30] | + | + | ||

| *[31] | + | |||

| *[32] | +/Ø | |||

| *[33] | + | + | ||

| *[34] | + | − | ||

| *[35] | + | |||

| *[36] | + | + | +/Ø | |

| Label/reformulation | ||||

| [6] | + labelling | |||

| +/- reformulation | ||||

| [20] | +/− (healthier diet quality) | |||

| [18] | + | + (sugar intake) | ||

| [21] | +/Ø | |||

| [19] | + (energy intake) | |||

| Environment only | ||||

| [6] | + | + | ||

| [27] | + | + (unhealthy snack intake) | ||

| *[38] | + | +/Ø | ||

| *[37] | + | |||

| *[40] | Ø | +/Ø | ||

| *[39] | + | +/Ø | ||

| *[34] | +/Ø | |||

| *[41] | + | + | ||

| Education only | ||||

| *[38] | + | +/Ø | ||

| *[37] | + | |||

| *[40] | Ø | +/Ø | ||

| *[39] | + | +/Ø | ||

| *[34] | +/Ø | |||

| Education/Environment | ||||

| [22] | +/Ø | |||

| [24] | +/− | |||

| [23] | + | Ø | ||

| [25] | + children and adolescents | |||

| Ø adults | ||||

| [26] | +/− | |||

| *[42] | +/Ø | |||

The different types of measures studied in the systematic reviews and their impact on sugar-sweetened beverages demand, sugar-sweetened beverages consumption, weight outcomes, and other outcomes. (Impact of measures aiming to reduce sugars intake in the general population and their implementation in Europe: a scoping review. Switzerland. 2019–2021).

Sugar-sweetened beverages.

Authors with an asterisk are the SRs included in the review of SRs of Kirkpatrick et al. [12].

+ Beneficial effects; reduction in SSB consumption or weight outcomes observed in the large majority of studies.

Ø No effect: no reduction in SSB consumption or weight outcomes observed.

− Negative effect: increase in SSB consumption or weight outcomes observed.

+/Ø or +/−: both beneficial and no effect/negative effect observed.

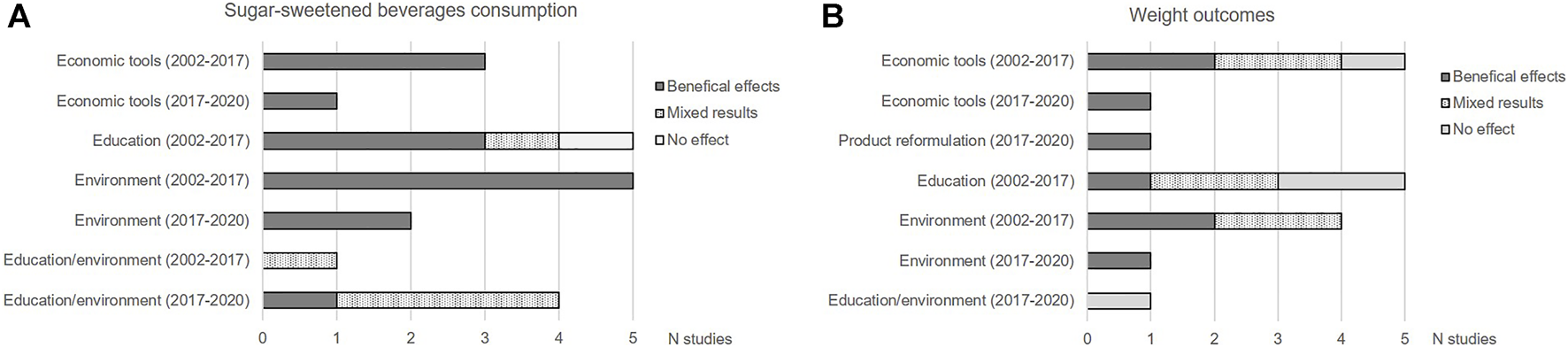

As shown in Figure 2, considering all types of measures, a beneficial impact on SSB consumption was observed in 15/21 SRs included in the review of Kirkpatrick et al. and published since 2017 [12]. Beneficial effects on SSB consumption were observed for economic tools and interventions focusing on environment alone whereas SRs on education and those combining educational and environmental interventions found mixed results. Regarding the impact on weight outcomes, the results were less concordant. In the most recent SRs, economic tools, reformulation, and environmental interventions showed beneficial effects.

FIGURE 2

Impact on the different types of measures on sugar-sweetened beverages consumption (A) and weight outcomes (B) in the systematic reviews included in the review of Kirkpatrick et al. and in the reviews published between 2017 and 2020. (Impact of measures aiming to reduce sugars intake in the general population and their implementation in Europe: a scoping review. Switzerland. 2019–2021).

Synthesis of NOURISHING Database

Several European countries have implemented measures aimed at reducing sugar consumption in the population. In the “Behaviour change communication” domain, information (I) and nutritional education (G) are the most widely implemented measures, as described in Table 4. In the “Food environment” domain, the most frequently implemented measures are labels (N), followed by environmental measures aiming to offer healthy food and set standards in public institutions and other specific settings (O), restricting food advertising and other forms of commercial promotion (R), and health-related food taxes (U). In contrast, only a few countries have implemented environmental measures in the following areas: improving the nutritional quality of the whole food supply, including reformulation (I) and setting incentives and rules to create a healthy retail and food service environment (S). In the “Food system” domain, only a few countries have implemented measures aiming at decreasing sugar intake in the population.

TABLE 4

| Nourishing classification | Implemented measures | Countries where implemented |

|---|---|---|

| N | Nutrition label standards and regulations on the use of claims and implied claims on food | Croatia, Denmark, EU countries, France, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom |

| O | Offer healthy food and set standards in public institutions and other specific settings | Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom |

| • Mandatory standards for food available in schools including restrictions on unhealthy food | ||

| • Mandatory regulation of food advertising on non-broadcast communications channels | ||

| • Mandatory regulation of food advertising through any medium | ||

| • Voluntary guidelines for food available in schools | ||

| • Bans specific to vending machines in schools | ||

| • Standards in other specific locations (e.g., health facilities workplaces) | ||

| U | Use economic tools to address food affordability and purchase incentives | Belgium, Estonia, Finland, France, Hungary, Ireland, Latvia, Norway, Portugal, Spain, United Kingdom |

| • Health-related food taxes | ||

| • Voluntary health-related foods taxes | ||

| R | Restrict food advertising and other forms of commercial promotion | Belgium, Denmark, European Commission, Finland, Hungary, Ireland, Latvia, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom |

| • Mandatory regulation of broadcast food advertising to children | ||

| • Voluntary regulation of food advertising on non-broadcast communications channels | ||

| • Governmental engage with industry to develop self-regulation to restrict food marketing to children | ||

| • Government support voluntary pledges developed by industry | ||

| I (Improve) | Improve nutritional quality of the whole food supply | France, Norway, Switzerland, United Kingdom |

| • Voluntary reformulation of food products | ||

| S | Set incentives and rules to create a healthy retail and food service environment | United Kingdom, France, Norway |

| • Initiatives to increase the availability of healthier food in stores and food service outlets | ||

| • Incentives and rules to offer healthy food options as a default in food service outlets | ||

| • Incentives and rules to restrict sugar-sweetened beverage consumption | ||

| H | Harness food supply chain & actions across sectors to ensure coherence with health | Finland United, Kingdom |

| I (Inform) | Inform people about food and nutrition through public awareness | Done in most countries |

| • Development and communication of food-based dietary guidelines | ||

| • Development and communication of guidelines for specific food groups | ||

| • Public awareness, mass media and informational campaigns and social marketing on healthy eating | ||

| • Public awareness campaigns specific to fruit and vegetables | ||

| • Public awareness campaigns concerning specific unhealthy food and beverages | ||

| N | No specific measures aiming at decreasing sugar intake in the population | |

| G | Give nutrition education and skills | Done in most countries |

| • Nutrition education on curricula | ||

| • Community-based nutrition education | ||

| • Cooking skills | ||

| • Initiatives to train school children on growing food | ||

| • Workplace or community health schemes | ||

| • Training for caterers and food service providers |

The different types of measures to decrease sugar intake implemented in countries according to NOURISHING (Impact of measures aiming to reduce sugars intake in the general population and their implementation in Europe: a scoping review. Switzerland. 2019–2021).

Discussion

The aim of this scoping review was to identify the types of measures implemented and evaluated to decrease sugars intake in the population and to assess their impact. We included 15 SRs published since 2017 and that assessed economic tools (n = 5), product reformulation and labels (n = 5), environmental interventions (n = 2), and educational/environmental interventions (n = 5). Despite high heterogeneity in the 15 SRs included, we observed a beneficial impact of economic tools and interventions focusing on environment alone on sugar intake, mostly with respect to SSB consumption whereas SRs combining educational and environmental interventions found mixed results. The impact on weight outcomes was less frequently studied but still showed a beneficial trend, especially in the most recent SRs evaluating economic tools, product reformulation, and environmental interventions. According to the NOURISHING database, the most frequently implemented measures in Europe were information through public awareness, nutritional education, and labels.

Among the three types of measures that have been studied in the SRs, economic tools, focusing mostly on health taxes, were studied by five SRs. The implementation of taxes has shown to be effective in reducing SSB purchases and consumption. The SR of Roberts et al. has shown that the reduction in SSB purchases may be proportionate to the level of price increase imposed [17]. Wright el al. concluded that a tax on SSBs higher than 20% of the initial price was more likely to have a positive impact on health behaviors and outcomes [30]. According to the NOURISHING database, economic tools have been implemented in several European countries, including Belgium, Estonia, Finland, France, Hungary, Ireland, Latvia, Norway, Portugal, Spain, and the United Kingdom. The level of the tax and the ways it has been implemented (e.g., definition of the foods and drinks subject to the tax) differs widely between countries. The majority of available evidence has shown a beneficial impact on short-term outcomes, mainly on SSB sales/consumption; however, other positive and long-term impacts should not be underestimated. The implementation of taxes on sugar may provide an incentive for the food industry to develop and promote healthier products. Some studies have extrapolated the long-term effects of a tax on SSB and concluded that they could reduce rates of illness, including obesity [31], mortality rates, health costs and increase quality of life [43–45].

The second type of measures that have been studied in the included SRs are product reformulation and labels/claims. Only three SRs have recently assessed the impact of product reformulation [6, 18, 19], mainly based on simulation and model studies. The results were promising on estimated sugar reduction and health outcomes; however, these results need to be confirmed in the community. This type of measure has the advantage of reducing consumers’ intake of certain nutrients without requiring a conscious effort on their part. The impact of labels and claims is more contrasted. These mixed results may be explained by the large variability in existing labels and their confusing effect on consumers, who may be lost at the time of purchase [46, 47]. The effects of claims were unsure because of potential compensatory behaviors. The NOURISHING database shows that product reformulation has been implemented only in four European countries, i.e., France, Norway, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. This type of measure may be difficult to implement, as it requires the involvement of several partners, mainly the food industry, and may present challenges in terms of foods technology. In contrast, the majority of European countries have already implemented labels and claims, which are often applied in the form of the nutritional composition available on food and drinks packages.

The third type of measures that have been studied in the included SRs are educational and environmental interventions, mostly implemented in a school setting. High heterogeneity was observed in the interventions that included educational initiatives, especially nutrition education curriculums, and/or environmental measures, such as the provision of healthful foods or beverages and quality standards for competitive foods and beverages. It is therefore difficult to assess the impact of each of these individual interventions, as they are frequently associated as recommended by current guidelines on prevention of overweight and obesity and health promotion. Educational measures place a lot of responsibility on individuals to make the final choice about their diet while the environmental conditions strongly influence food choices and adequate conditions clearly promote healthy choices. In this scoping review, the findings of environmental interventions alone were more striking than education alone or a combination of educational/environmental measures. Educational interventions still remain important tools in order to improve the nutritional knowledge and food literacy of the population, and facilitate the acceptability of environmental measures. Therefore, both types of measures should be combined in a coherent approach in order to avoid nutritional aberrations resulting from the different messages and stakeholders. Monitoring of the measures is also crucial in order to validate and/or adapt these measures according to the results. Targeted evaluations of the measures in terms of the resources invested, the process, and the results obtained are essential. The NOURISHING framework may be useful for the various stakeholders to clarify the types of measures implemented and their coherence, and to structure the intervention in a comprehensive approach.

Our scoping review has some limitations. First, the SRs included in our review included mainly adults and children in a school setting, and some subgroups of the population were not represented, such as preschool children, pregnant women, and the elderly. Moreover, the studies were mostly conducted in the US and Europe, thus affecting the external validity of our findings. Secondly, we only searched for the measures implemented in European countries in the NOURISHING database and not those implemented worldwide. Thirdly, the quality of the original studies included in the SRs was often considered to have high risk of bias by the authors, which may affect the internal validity of the findings. The weaknesses of the studies were often related to data collection related to sugar intake, the definition of sugars, or the duration of interventions. In relation to the SRs included in our review, the study designs of included original studies were heterogenous, the measures to decrease sugar intake were also highly variable, and the outcome most frequently studied was reduction in SSB purchases and consumption. However, this intermediate outcome, widely used as a surrogate for total sugar intake, does not consider substitutions or compensatory behaviors.

In conclusion, this scoping review shows that three types of measures have been studied in SRs, including economic tools, product reformulation and labels, and education/environmental interventions. A high level of heterogeneity was observed in the methodologies, populations, and interventions in the original studies. Economic tools and environmental interventions were effective to reduce sugar intake, as mostly assessed by SSB purchases and consumption. Interventions combining educational and environmental measures found mixed results. The findings on weight outcomes were less concordant but still showed a positive trend, especially for product reformulation. Some of these measures are used in Europe, but the most frequently implemented measures to date are information through public awareness, nutritional education, and labels. To close the large gap between sugar intake recommendations and actual intake, future measures should be implemented based on the available evidence using a global approach and integrating a thorough long-term evaluation.

Statements

Author contributions

SBDT and CJC designed the study, collected and analyzed the data, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and revised the final manuscript. CM collected the data, participated in data analysis and revised the final manuscript. SBDT and CJC have contributed equally to this work.

Funding

This scoping review was funded by the Geneva School of Health Sciences, HES-SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland, and is partly based on a scientific report on sugar which was commissioned by the Swiss Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office FSVO.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Elisabeth Guadagnolo and Alicia Marti for their support in data collection and our colleagues from the Department of Nutrition and Dietetics for their scientific support provided for the previous report on sugar intake in Switzerland. We thank Jean-David Sandoz, librarian at the University of Applied Sciences, Geneva, for his support in conducting the literature search. We also thank Steffi Schluechter, from the Swiss Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office, for sharing her knowledge on sugar intake in the Swiss population.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.ssph-journal.org/articles/10.3389/ijph.2021.1604108/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Bellou V Belbasis L Tzoulaki I Evangelou E . Risk Factors for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Exposure-wide Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses. PLoS One (2018) 13:e0194127. 10.1371/journal.pone.0194127

2.

Neuenschwander M Ballon A Weber KS Norat T Aune D Schwingshackl L . Role of Diet in Type 2 Diabetes Incidence: Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses of Prospective Observational Studies. BMJ (2019) 366:l2368. 10.1136/bmj.l2368

3.

Malik VS Li Y Pan A De Koning L Schernhammer E Willett WC . Long-Term Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened and Artificially Sweetened Beverages and Risk of Mortality in US Adults. Circulation (2019) 139:2113–25. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.037401

4.

Valenzuela MJ Waterhouse B Aggarwal VR Bloor K Doran T . Effect of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages on Oral Health: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur J Public Health (2021) 31:122–9. 10.1093/eurpub/ckaa147

5.

World Health Organization. Guideline Sugars Intake for Adults and Children. Geneva: World Health Organization (2015).

6.

von Philipsborn P Stratil JM Burns J Busert LK Pfadenhauer LM Polus S . Environmental Interventions to Reduce the Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Their Effects on Health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2019) 6:CD012292. 10.1002/14651858.CD012292.pub2

7.

Azaïs-Braesco V Sluik D Maillot M Kok F Moreno LA . A Review of Total & Added Sugar Intakes and Dietary Sources in Europe. Nutr J (2017) 16:6. 10.1186/s12937-016-0225-2

8.

Chatelan A Gaillard P Kruseman M Keller A . Total, Added, and Free Sugar Consumption and Adherence to Guidelines in Switzerland: Results from the First National Nutrition Survey menuCH. Nutrients (2019) 11:1117. 10.3390/nu11051117

9.

Walton J Bell H Re R Nugent AP . Current Perspectives on Global Sugar Consumption: Definitions, Recommendations, Population Intakes, Challenges and Future Direction. Nutr Res Rev (2021) 2021:1–22. 10.1017/S095442242100024X

10.

Hawkes C Jewell J Allen K . A Food Policy Package for Healthy Diets and the Prevention of Obesity and Diet-Related Non-communicable Diseases: the NOURISHING Framework. Obes Rev (2013) 14(Suppl. 2):159–68. 10.1111/obr.12098

11.

World Cancer Research Fund. World Cancer Research Fund International NOURISHING and MOVING Policy Database (2021). Available from: https://policydatabase.wcrf.org/ (Accessed 03 24, 2021).

12.

Kirkpatrick S Raffoul A Maynard M Lee K Stapleton J . Gaps in the Evidence on Population Interventions to Reduce Consumption of Sugars: A Review of Reviews. Nutrients (2018) 10:1036. 10.3390/nu10081036

13.

Bucher Della Torre S Jotterand Chaparro C . Rapport sur la mise en place de mesures visant une réduction de la consommation de sucre en Suisse. Genève: Genève (2019).

14.

Moher D Liberati A Tetzlaff J Altman DG . Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Ann Intern Med (2009) 151:264–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

15.

Teng AM Jones AC Mizdrak A Signal L Genç M Wilson N . Impact of Sugar‐sweetened Beverage Taxes on Purchases and Dietary Intake: Systematic Review and Meta‐analysis. Obes Rev (2019) 20:1187–204. 10.1111/obr.12868

16.

Pfinder M Heise TL Hilton Boon M Pega F Fenton C Griebler U . Taxation of Unprocessed Sugar or Sugar-Added Foods for Reducing Their Consumption and Preventing Obesity or Other Adverse Health Outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2020) 4:CD012333. 10.1002/14651858.CD012333.pub2

17.

Roberts KE Ells LJ McGowan VJ Machaira T Targett VC Allen RE . A Rapid Review Examining Purchasing Changes Resulting from Fiscal Measures Targeted at High Sugar Foods and Sugar-Sweetened Drinks. Nutr Diabetes (2017) 7:302. 10.1038/s41387-017-0001-1

18.

Hashem KM He FJ MacGregor GA . Effects of Product Reformulation on Sugar Intake and Health-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutr Rev (2019) 77:181–96. 10.1093/nutrit/nuy015

19.

Grieger JA Johnson BJ Wycherley TP Golley RK . Evaluation of Simulation Models that Estimate the Effect of Dietary Strategies on Nutritional Intake: A Systematic Review. J Nutr (2017) 147:908–31. 10.3945/jn.116.245027

20.

Anastasiou K Miller M Dickinson K . The Relationship between Food Label Use and Dietary Intake in Adults: A Systematic Review. Appetite (2019) 138:280–91. 10.1016/j.appet.2019.03.025

21.

Oostenbach LH Slits E Robinson E Sacks G . Systematic Review of the Impact of Nutrition Claims Related to Fat, Sugar and Energy Content on Food Choices and Energy Intake. BMC Public Health (2019) 19:1296. 10.1186/s12889-019-7622-3

22.

Dibay Moghadam S Krieger JW Louden DKN . A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Promoting Water Intake to Reduce Sugar‐sweetened Beverage Consumption. Obes Sci Pract (2020) 6:229–46. 10.1002/osp4.397

23.

Abdel Rahman A Jomaa L Kahale LA Adair P Pine C . Effectiveness of Behavioral Interventions to Reduce the Intake of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages in Children and Adolescents: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutr Rev (2018) 76:88–107. 10.1093/nutrit/nux061

24.

Wright KM Dono J Brownbill AL Pearson Gibson OO Bowden J Wycherley TP . Sugar-sweetened Beverage (SSB) Consumption, Correlates and Interventions Among Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities: a Scoping Review. BMJ open (2019) 9:e023630. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023630

25.

Vargas-Garcia EJ Evans CEL Prestwich A Sykes-Muskett BJ Hooson J Cade JE . Interventions to Reduce Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages or Increase Water Intake: Evidence from a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obes Rev (2017) 18:1350–63. 10.1111/obr.12580

26.

Vézina-Im L-A Beaulieu D Bélanger-Gravel A Boucher D Sirois C Dugas M . Efficacy of School-Based Interventions Aimed at Decreasing Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption Among Adolescents: a Systematic Review. Public Health Nutr (2017) 20:2416–31. 10.1017/S1368980017000076

27.

Micha R Karageorgou D Bakogianni I Trichia E Whitsel LP Story M . Effectiveness of School Food Environment Policies on Children's Dietary Behaviors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One (2018) 13:e0194555. 10.1371/journal.pone.0194555

28.

Sterne JA Hernán MA Reeves BC Savović J Berkman ND Viswanathan M . ROBINS-I: a Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Non-randomised Studies of Interventions. BMJ (2016) 355:i4919. 10.1136/bmj.i4919

29.

Sterne JAC Savović J Page MJ Elbers RG Blencowe NS Boutron I . RoB 2: a Revised Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials. BMJ (2019) 366:l4898. 10.1136/bmj.l4898

30.

Wright A Smith KE Hellowell M . Policy Lessons from Health Taxes: a Systematic Review of Empirical Studies. BMC Public Health (2017) 17:583. 10.1186/s12889-017-4497-z

31.

Backholer K Sarink D Beauchamp A Keating C Loh V Ball K . The Impact of a Tax on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages According to Socio-Economic Position: a Systematic Review of the Evidence. Public Health Nutr (2016) 19:3070–84. 10.1017/S136898001600104X

32.

Bes-Rastrollo M Sayon-Orea C Ruiz-Canela M Martinez-Gonzalez MA . Impact of Sugars and Sugar Taxation on Body Weight Control: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Obesity (2016) 24:1410–26. 10.1002/oby.21535

33.

Cabrera Escobar MA Veerman JL Tollman SM Bertram MY Hofman KJ . Evidence that a Tax on Sugar Sweetened Beverages Reduces the Obesity Rate: a Meta-Analysis. BMC Public Health (2013) 13:1072. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1072

34.

Levy DT Friend KB Wang YC . A Review of the Literature on Policies Directed at the Youth Consumption of Sugar Sweetened Beverages. Adv Nutr (2011) 2:182S–200S. 10.3945/an.111.000356

35.

Nakhimovsky SS Feigl AB Avila C O’Sullivan G Macgregor-Skinner E Spranca M . Taxes on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages to Reduce Overweight and Obesity in Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. PLoS One (2016) 11:e0163358. 10.1371/journal.pone.0163358

36.

Powell LM Chriqui JF Khan T Wada R Chaloupka FJ . Assessing the Potential Effectiveness of Food and Beverage Taxes and Subsidies for Improving Public Health: a Systematic Review of Prices, Demand and Body Weight Outcomes. Obes Rev (2013) 14:110–28. 10.1111/obr.12002

37.

Althuis MD Weed DL . Evidence Mapping: Methodologic Foundations and Application to Intervention and Observational Research on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Health Outcomes. Am J Clin Nutr (2013) 98:755–68. 10.3945/ajcn.113.058917

38.

Avery A Bostock L McCullough F . A Systematic Review Investigating Interventions that Can Help Reduce Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages in Children Leading to Changes in Body Fatness. J Hum Nutr Diet (2015) 28(Suppl. 1):52–64. 10.1111/jhn.12267

39.

Gibson S . Sugar-sweetened Soft Drinks and Obesity: a Systematic Review of the Evidence from Observational Studies and Interventions. Nutr Res Rev (2008) 21:134–47. 10.1017/S0954422408110976

40.

Malik VS Pan A Willett WC Hu FB . Sugar-sweetened Beverages and Weight Gain in Children and Adults: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Clin Nutr (2013) 98:1084–102. 10.3945/ajcn.113.058362

41.

Malik VS Schulze MB Hu FB . Intake of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Weight Gain: a Systematic Review. Am J Clin Nutr (2006) 84:274–88. 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.27410.1093/ajcn/84.2.274

42.

Mazarello Paes V Hesketh K O'Malley C Moore H Summerbell C Griffin S . Determinants of Sugar‐sweetened Beverage Consumption in Young Children: a Systematic Review. Obes Rev (2015) 16:903–13. 10.1111/obr.12310

43.

Manyema M Veerman LJ Tugendhaft A Labadarios D Hofman KJ . Modelling the Potential Impact of a Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax on Stroke Mortality, Costs and Health-Adjusted Life Years in South Africa. BMC Public Health (2016) 16:405. 10.1186/s12889-016-3085-y

44.

Sánchez-Romero LM Penko J Coxson PG Fernández A Mason A Moran AE . Projected Impact of Mexico's Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax Policy on Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease: A Modeling Study. Plos Med (2016) 13:e1002158. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002158

45.

Veerman JL Sacks G Antonopoulos N Martin J . The Impact of a Tax on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages on Health and Health Care Costs: A Modelling Study. PLoS One (2016) 11:e0151460. 10.1371/journal.pone.0151460

46.

Moore S Donnelly J Jones S Cade J . Effect of Educational Interventions on Understanding and Use of Nutrition Labels: A Systematic Review. Nutrients (2018) 10:1432. 10.3390/nu10101432

47.

Campos S Doxey J Hammond D . Nutrition Labels on Pre-packaged Foods: a Systematic Review. Public Health Nutr (2011) 14:1496–506. 10.1017/S1368980010003290

Summary

Keywords

taxation, sugars, sugar-sweetened beverages, food environments, nutrition education, population interventions, scoping review

Citation

Bucher Della Torre S, Moullet C and Jotterand Chaparro C (2022) Impact of Measures Aiming to Reduce Sugars Intake in the General Population and Their Implementation in Europe: A Scoping Review. Int J Public Health 66:1604108. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2021.1604108

Received

25 March 2021

Accepted

30 November 2021

Published

13 January 2022

Volume

66 - 2021

Edited by

Karin De Ridder, Sciensano, Belgium

Reviewed by

Peter Von Philipsborn, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Germany

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Bucher Della Torre, Moullet and Jotterand Chaparro.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sophie Bucher Della Torre, sophie.bucher@hesge.ch

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.