Abstract

Objective: Iran is one of the main hosts of Afghan refugees. This study aims to provide comprehensive evidence to increase Afghan migrants’ access to healthcare services in Iran.

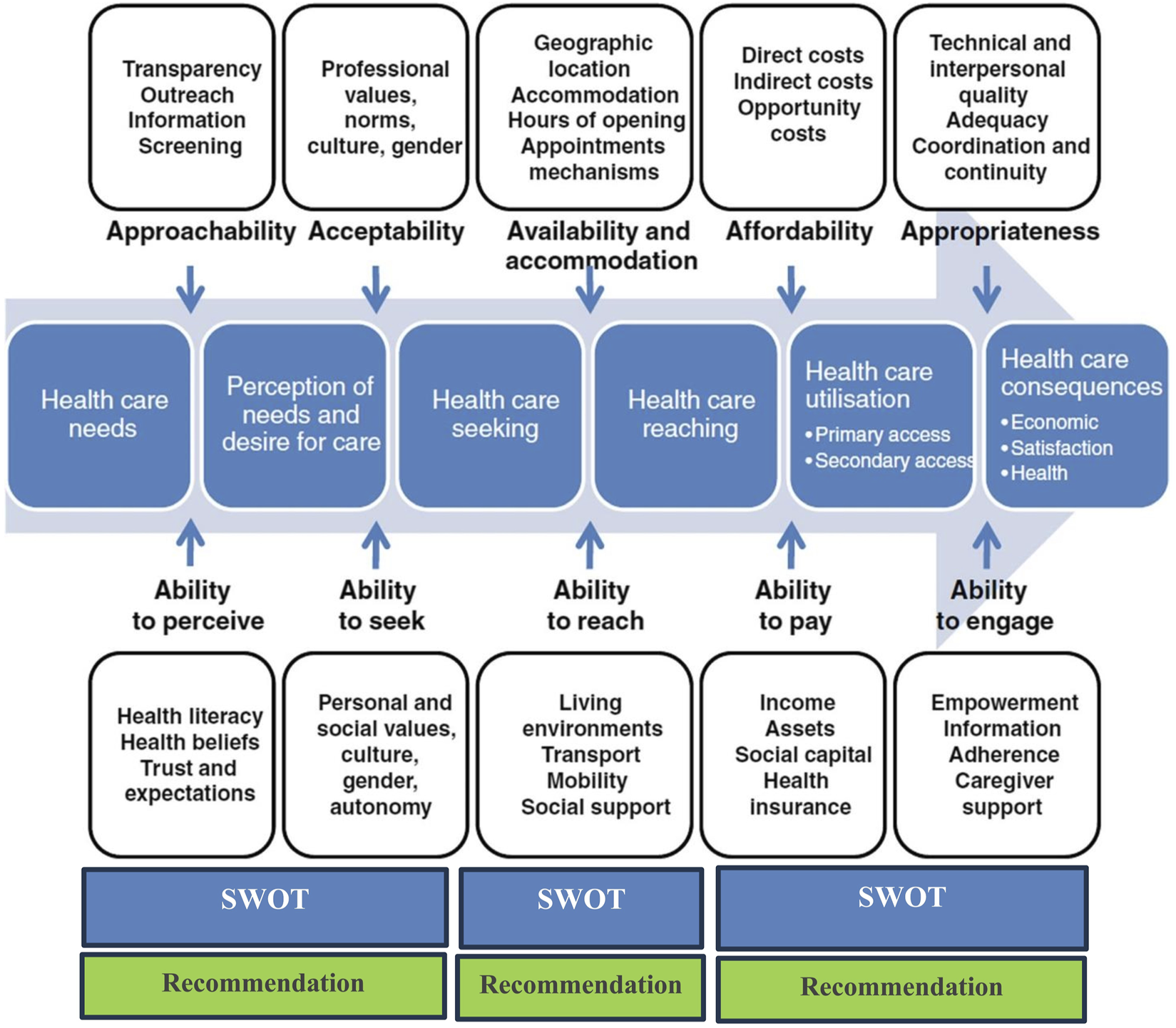

Methods: To assess the health system’s response to Afghan migrants in Iran, we conducted three phases for SWOT analysis, including: 1-developing a review and comprehensive analysis of documents, laws, and, programs, 2-conducting semi-structured interviews with policymakers and experts, and 3-mapping the results through the Levesque’s conceptual framework for healthcare access.

Results: We evaluated the response of the health system to Afghan migrants’ health needs in three domains: 1-Approachability and ability to perceive migrants; 2-Ability to reach, engage, and availability and accommodation and appropriateness; 3-The ability to pay and affordability. For each of the three domains, we identified strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats, complemented with evidence-based suggestions to improve migrants’ access to needed healthcare services.

Conclusion: Given the rising trend of immigration and deteriorating financial crises, we recommend appropriate strategies for the adoption of specialized focus services, gateway services, and restricted services. Also simplifying financial procedures, and implementing innovative insurance mechanisms are essential.

Introduction

The United Nations (UN) defines a refugee as “someone who changes his or her country of usual residence, regardless of the reason for migration or legal status” and a migrant as “any person who is outside a State of which they are a citizen or national, or, in the case of a stateless person, their State of birth or habitual residence.” This definition does not include the hardships of this type of residential change. Refugees stand among the most vulnerable people, whose numbers are on the rise [1]. According to the UN Refugees Agency’s estimations in 2023, as a result of harassment, conflict, violence, human rights violations, or other events that disrupted public order, 108.4 million people will be relocated around the world, 35.3 million of whom were classified as Refugees, 5.4 million as Asylum seekers, 62.5 million as Internally displaced people (IDPs), and 5.2 million other people in need of international protection [2]. Just three countries account for more than half of the world’s refugees and other individuals in need of international protection; (Syrian Arab Republic: 6.8 million, Ukraine 5.7 million, Afghanistan 5.7 million of which 3,400,000 are in Iran) [3, 4]. In line with the previous year, 56% of all persons evacuated across borders resided in only 10 countries; Turkey, Pakistan, and Iran are the top three on this list. In this paper, our main focus will be on Afghan refugees currently residing in Iran [2].

Afghan refugees’ registrations began in 1979 in Iran, peaked in the 1990s (3 million), and remained stable until 2004 (around 1 million). According to the 2016–17 National Population and Housing Census, 1,654,388 foreign nationals lived in 31 provinces across Iran, of whom 1,583,979 were of Afghan origin. Although it is estimated that 8 million Afghans live in Iran, the majority of whom are undocumented and therefore are not counted in the national census [5].

The main health problems of Afghan migrants in Iran are non-communicable diseases (NCDs), communicable diseases, food insecurity and malnutrition, Low immunization coverage, and Psychological disorders [6]. Although healthcare facilities in Iran are available to provide healthcare services to Afghan migrants for any given illness, as most of them are uninsured, affordability to pay is a big challenge that has led to deteriorating their health status over time.

Various countries have developed four care models to serve refugee and migrant populations that include mainstream services, specialized-focus services, gateway services, and limited services [5]. Since the introduction of the health transformation plan (HTP) to reach a universal public health insurance program in 2015, Iran has adopted a mainstream model of care to serve its refugee and migrant population, allowing all UNHCR-registered refugees living in the Islamic Republic of Iran to access the same level of health services as Iranian citizens. Refugees can sign up for the program at the local government offices and receive care at government hospitals and clinics. The Iranian government, UNHCR, and other donors are all contributing to the program. UNHCR covers the costs of premiums for the most vulnerable refugees, while other refugees must pay their premiums.

Barriers obstruct the process of receiving healthcare in a variety of ways. The Levesque conceptual framework for healthcare access provides policymakers with a clear perspective of the effect areas by including characteristics such as perception of health needs and desire to care, healthcare seeking, healthcare reaching, and healthcare utilization [7]. The literature identified the most important barrier for migrants to receive health services is their ability to pay [7, 8]. Various characteristics could affect migrants’ ability to pay, i.e., the host country’s labor laws, migrants’ insurance coverage, migrants’ income, type of employment, and tax legislation.

This study aims to provide evidence to increase migrants’ access to healthcare services. We conducted a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) analysis of Iran’s health system to develop access to healthcare services based on Levesque’s conceptual framework, followed by recommendations for the Iranian health system.

Methods

Study Design

SWOT Analysis is a strategic planning tool to identify the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats present in a project, or any other scenario that requires a decision (organization or program). Internal and external elements and existing and future possibilities are all evaluated in a SWOT analysis [

9]. SWOTs are defined using the following criteria:

• Strengths are internal organizational characteristics that aid in the achievement of the goal.

• Weaknesses are internal organizational characteristics that obstruct the achievement of the goal.

• External factors that aid in attaining the goal are referred to as opportunities.

• External conditions that are adverse to achieving the goal are referred to as threats [9].

According to the Revised SWOT analysis, which is developed for healthcare organizations; Stakeholder expectations, resources, and contextual factors should all be considered [10]. We designed and conducted three phases to complete the SWOT analysis of Iran’s health system response to Afghan migrants.

was conducted in two steps, as follows:

I. Investigating Iran’s background in healthcare planning for Afghan migrants (including content analysis of documents, laws, and programs),

II. Identifying SWOT items and policy recommendations by conducting semi-structured interviews with policymakers, administrators, migrants, and experts;

Data Collection

This is a qualitative study. We collected data through a comprehensive review of laws, regulations, and associated documents related to foreign nationals in the legal systems of Iran, followed by semi-structured, face-to-face, in-depth interviews.

Comprehensive Review of Laws, Regulations, and Associated Documents

To provide a comprehensive literature review of laws and other related documents, the National Database of Parliamentary Laws and Regulations [11], the government [12], and the Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MoHME) [13] were searched using terms: foreign nationals, refugees, immigrants, or asylum seekers and health, healthcare, treatment, employment, or insurance. These databases contain all laws and regulations passed by the government, parliament, and ministries as well as a history of laws, back since 1906. In addition, we searched the websites of the MoHME, the Iranian Health Insurance Organization (IHIO), the Bureau for Aliens and Foreign Immigrants Affairs website (BAFIA), and other related organizations. To ensure inclusivity and identification of all related materials, two researchers worked independently on the inquiry.

Semi-Structured Interviews

We conducted 76 semi-structured, face-to-face, in-depth interviews with a purposively selected diverse group of participants including government administrators, Afghan (documented and undocumented), MoHME officials, healthcare providers, representatives from insurance organizations, employers of Afghan in Iran, NGOs, and academics, with the experience of participating in the planning, decision-making, and support of migrant healthcare programs (See Table 1 for details). The interview guide was developed using Levesque’s conceptual framework for healthcare access. We assured the interviewees of anonymity and confidentiality and obtained their written or verbal consent before the interview. Interviews lasted 18–80 min (interviews with refugees took less time), digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. We also took notes during the interview and sought feedback from selected interviewees and held several meetings for data interpretation.

TABLE 1

| Type of interviewees, expertise | Number | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MoHME | Managers and experts of related departments | 9 |

| 2 | State Walfare Organization of Iran | Expert in migrant affairs | 1 |

| 3 | Rehabilitation center | Expert in migrant affairs | 1 |

| 4 | UNHCR | Expert in migrant affairs | 2 |

| 5 | BAFIA | Expert in migrant affairs | 1 |

| 6 | NGOs | 21 | |

| 7 | IHIO | Expert in migrant affairs | 1 |

| 8 | Asia and Alborz insurance | Expert in migrant affairs | 2 |

| 9 | Social Security Organization | Expert in migrant affairs | 3 |

| 10 | Health services provider (Hospitals, health houses, and health posts) | Manager, physician, nurse, PHC staff | 20 |

| 11 | Afghan migrants | Legal and illegal migrants, with insurance, without insurance | 11 |

| 12 | Other | hospital charity | 4 |

The characteristics of interviewees (Iran, 2023).

Data Analysis

We used MAXQDA Version 10 software for data management and content analysis of documents and interviews. Three researchers carried out the analysis of interviews and related documents using the framework analysis approach. We considered the Levesque conceptual framework for healthcare access as the thematic framework. Differences in coding were discussed to establish consensus, sub-themes were found, a hierarchy of topics was constructed, and a general coding and framework (see Supplementary Appendix SA for further detail). We developed a preliminary list of SWOT and recommendation items based on the findings in Supplementary Appendix SA.

Phase 2: Best experiences and recommendations based on a scoping review.

We conducted a scoping review to identify and understand the best experiences and recommendations to provide optimal responses of health systems to the health needs of migrants around the world. The following five steps were carried out:

Step one: Study Questions;

Step two: Identification of relevant studies; (Study time frame, databases, and websites, the search terms);

Step three: Selection of included studies;

Steps four and five: charting data; organizing, summarizing, and reporting the results [14].

Detailed information on each step and related methods and results is presented in Supplementary Appendix SB.

Phase 3: Mapping the result of the scoping review and SWOT based on Levesque’s conceptual framework for healthcare access.

In the final phase, three researchers independently categorized the results of the first two phases into the structures of SWOT dimensions and Levesque’s conceptual framework [15, 16]. The framework presents a comprehensive assessment of healthcare access, which includes variables such as approachability, acceptability, availability/accommodation, affordability, and appropriateness. It takes into account the socioeconomic characteristics of the community to include the five comparable capacities of individuals and populations to recognize, seek, reach, pay for, and engage in healthcare. Levesque’s conceptual framework was selected as one of the most comprehensive models because it takes into account various social, cultural, and economic dimensions as a series of processes of access to health services, as well as the viewpoint of the provider, the patient, policymakers, and health managers.

To address the disagreements in the categories, the results were unified, and the conflicting cases were discussed by all members of the study team. Thus, each component of the framework contains a SWOT analysis based on Iran’s situation (Figure 1).

Results

Below, are the five categories in which the content of the documents and experts’ opinions were analyzed:

❖ A.1 Iran’s accession to international conventions on refugees;

❖ A.2 Migrants’ Healthcare rights in Iran;

❖ A.3 Migrants’ right for access to healthcare services in Iran;

❖ A.4 Health insurance schemes for migrants in Iran;

❖ A.5 Health services and financial protection for migrants; barriers and challenges in the Islamic Republic of Iran;

Supplementary Appendix SA provides more detail about phase one of Iran’s situation. In phase two; following the initial search, we found 1,590 articles, 254 of which were removed as duplicates. We reviewed the titles and abstracts of 1,336 articles and excluded 1,155 articles due to lack of relevance to the current study. Finally, 34 studies were selected based on the study criteria. Supplementary Appendix SB presents a set of countries’ experiences and recommendations for migrant health.

We considered all dimensions and complexities of healthcare access to address all related issues. Levesque’s Conceptual Framework of Access to Health, published in 2013, investigates the five dimensions of access as well as the five abilities of the population to access healthcare. Tables 2–4 present the details of global recommendations as well as an analysis of Iran’s situation in each of Levesque’s dimensions.

TABLE 2

| SWOT | Recommendation based scoping review and interview | Details | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approachability and acceptability, Ability to perceive and ability to seek | S |

|

|

-Appendix A. Sections A.1. & A.2, A.3, A.5.1 and related quotations, & A5.2 and related quotations. -Appendix B |

| W |

|

|||

| O |

|

|||

| T |

|

|||

TABLE 3

| SWOT | Recommendation based scoping review and interview | Details | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ability to Reach and Availability and Accommodation & Ability to engage and appropriateness | S |

|

|

-Appendix A. Sections A.3, A.4, A.5.3 and related quotations. -Appendix B |

| W |

|

|||

| O |

|

|||

| T |

|

|||

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats and recommendation for the ability to reach and availability [22] (Iran, 2023).

TABLE 4

| SWOT | Recommendation based scoping review and interview | Details | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ability to pay and Affordability | S |

|

|

-Appendix A. Sections A.3, A.4, A.5.4 and related sub-sections and quotations. -Appendix B |

| W |

|

|||

| O |

|

|||

| T |

|

|||

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats and recommendation for the ability to pay and affordability [19] (Iran, 2023).

Approachability and Ability to Perceive of Migrants

Iran has approved most international conventions relating to migrants. The country is currently home to 3,400,000 refugees, and the majority of them are Afghans [4]. It is estimated approximately 2.1–6 million undocumented Afghans are living in Iran [23]. Since the recent upheaval in Afghanistan, the number of Afghans seeking international assistance has increased remarkably. Accordingly, it has been estimated that 500,000–1,000,000 have fled to Iran. By 31 December 2022, 5.2M million refugees and asylum-seekers from Afghanistan are reported in neighboring countries [24, 25]. These refugees need urgent help and support to meet basic needs such as food and shelter. Despite domestic constraints and economic challenges, Iran has been able to carry out many interventions emphasized by the conventions. However, UHC for migrants is still a long way off. Due to the lingual, cultural, social, and religious similarities between the Iranian and Afghan people, access to healthcare for Afghan migrants has not been a considerable challenge in Iran [26]. For instance, female patients can seek healthcare services through female providers. Moreover, there is no requirement for a legal certificate to receive PHC services, documented migrants have the right to use recognized healthcare facilities, and undocumented migrants are not exposed to any legal restrictions; however, other issues that have been mentioned prevent them from using the service.

One of the greatest obstacles to migrants’ access at this level has been the absence of a coherent assessment of the health status and health risks of recently arrived migrants, as well as a consistent program to inform and familiarize them with the health rights and facilities in Iran’s health system. It is highly uncommon to introduce migrants to and raise their awareness of Iran’s healthcare system through group visits, as opposed to giving them individualized care. In addition, while being one of the community-based initiatives that use volunteers to improve population health, the potential of health ambassadors have not been meaningfully utilized for migrants [27]. One subject that requires capacity building, especially for vulnerable groups, is weakness in the proactive identification of health needs, especially for undocumented migrants, and inter-organizational/inter-sectoral care pathways, notably between migration organizations and the health system.

Opportunities to expand access at this level include migrant health volunteers, migrant communities where residents are concentrated, and the integration of migrants within the society rather than residing in the camps and isolation. In addition, the concentration of migrants in specific provinces and neighborhoods, plus the wide internet and mass media coverage can foster migrants’ access to health services. However, migrants’ access to healthcare has been compromised due to their poor health status in their country of origin, differences in health attitudes, marginalization, insufficient health literacy, identity, and residency status, and difficulties with employment contracts.

Ability to Reach and Availability and Accommodation & Ability to Engage and Appropriateness

Comprehensive health centers in urban and rural settings are the main part of the primary healthcare system (PHC) that provides healthcare services to both Iranian citizens and migrants (mainstream model). The simultaneous presence of male and female healthcare workers and the availability of nutrition and psychology counselors at PHCs are the strengths of Iran’s health system at the first level of access. Lack of initial comprehensive health assessment or “welcome visit” to new migrants; not using mixed models of care that contain additional models such as specialized focus services and gateway services, and low number of health workers per capita are the most important weaknesses at this level of access to health services for migrants.

Ability to Pay and Affordability

The deployment of inappropriate procedures in collecting, pooling, and allocating insurance premiums, along with inadequate resources have restricted migrants’ access to healthcare services at this level. We advocate removing such barriers by adopting a sliding scale of premiums and simplifying the enrollment process for migrants.

Discussion

Integrating SWOT analysis and Levesque’s conceptual framework with country-specific examples can provide policymakers with evidence-based guidance for developing the most effective policies for migrants. Our findings revealed that health officials’ emphasis on the six building blocks of a health system has led to difficulties with people’s access to health services, particularly for migrants [25]. Insufficient system thinking approach in policymaking for the health system has shown a negative impact on the health system’s outcome. We advocate policymakers consider both the supply (health system) and demand (people) sides when establishing programs and policies. There are sid-systems, sub-systems, and stakeholders on both the supply and demand sides that have an impact on the investigated system, both positively and negatively. A study on the System Dynamics Approach to Immunization in Uganda found that many subsystems influence the success of the immunization program, including mothers’ level of literacy, the effect of the media, the level of civil unrest, transportation constraints and availability and costs, and poor incentives for health workers [29, 30].

By scheduling a welcoming visit to basic healthcare facilities, it is feasible to evaluate the present health situation and health risk assessment for recently arrived migrants [31]. Among Afghan refugees, there are many volunteers available to provide services to migrants. Inter-organizational/inter-sectoral care pathways, group visits instead of individual care, community health workers, and document-issuance facilitation can all be used as interventions to enhance awareness of health plans and benefits. It will significantly reduce the barriers to access those migrants face as a result of the approachability [15]. In addition, simplifying financial processes for migrants, for example, innovative ways for revenue generation, paying the insurance premiums payment in installments, simplifying the enrollment procedure [32, 22], integrating enrollment sources, changing the enrollment unit, and improving premium collection approaches can help them to manage their spiraling expenses [33].

Recommendation

Despite initiatives to ensure that everyone has access to healthcare, there are still inequalities between migrant and non-migrant populations in terms of their ability to obtain services [1]. Although fluctuating, during the last two decades, over 10% of people have been uninsured in Iran [28]. Worse still, 2 to 5 million migrants, most of whom are uninsured, and a significant portion of the informal economy have challenged obtaining adequate health coverage for migrants. We propose adopting mixed healthcare models, e.g., specialized focus services, gateway services, and restricted services, to overcome the high number of migrants, financial crises, migration cycles, places of migrants’ entry, and the concentration of migrants in certain provinces [29]. Such an approach might also help address various health needs of migrants in their first year of arrival and the following years [34].

Migrants may live and work in different countries until permanent settlement. We propose the UNHCR to pave the way for the establishment of international or regional multinational social insurance firms to deal with migrants’ health insurance and pension continuously and efficiently. This mechanism may reduce migrants’ low willingness to pay insurance premiums due to their uncertain plan to either move to another country or return to their homeland.

Limitations

Migrants’ health is considered a complex and non-linear global health concern with many variables that could change over time. Our approach to SWOT analysis does not take into account the long-term outcomes and consequences of policies or interventions. Although it can provide beneficial insights into short-term changes in health outcomes, there is a limited capacity to predict the effects of changes on migrants in the long-term future. Accordingly, we advocate future studies to address the precise health status and needs of migrants, financial reevaluation, and redesign of regional and national insurance policies to create more effective insurance policies for better healthcare services coverage of migrants. We tried to be as diverse as possible in selecting the interviewees and tried our best to include Afghans with and without, insurance, as well as having and not having a chronic condition, etc. As over 80% of Afghan migrants in Iran are under 45 years old, we only included this range age in our study. We could not take into account various Afghan ethnic groups while selecting them for interviews.

Conclusion

Iran has adopted the mainstream services model to provide essential healthcare services to migrants regardless of their legal status. Despite its advantages, this strategy has specific challenges in providing the migrant community with proper health coverage. To ensure greater sustainability and better health outcomes, in line with our findings, we propose a mixed-method strategy to enhance migrants’ equitable access to healthcare services. Further, capacity building, promoting migrants’ engagement in decision-making for health, improving health literacy, proactive identification of health needs, and facilitating the financial process are all important components of ensuring that migrants have access to the healthcare they need in Iran.

Statements

Ethics statement

This study received ethical approval from the Ethical Committee of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences; all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The research was registered with the Eastern Mediterranean Region of the World Health Organization and received their approval.

Author contributions

AmT and AB conceived the study. AmT supervised all phases of evaluation and critically revised the manuscript; he is the guarantor. AB collected and conducted primary data collection and analysis, and drafted the manuscript. AO, MB, AfT, SS, and SK assisted in data collection and provided feedback on the result and manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.ssph-journal.org/articles/10.3389/ijph.2023.1606268/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Lebano A Hamed S Bradby H Gil-Salmerón A Durá-Ferrandis E Garcés-Ferrer J et al Migrants’ and Refugees’ Health Status and Healthcare in Europe: A Scoping Literature Review. BMC Public Health (2020) 20(1):1039. 10.1186/s12889-020-08749-8

2.

UNHCR. UNHCR’s Refugee Population Statistics Database (2021). Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/ (Accessed July 28, 2023).

3.

Milosevic D Cheng IH Smith MM . The NSW Refugee Health Service - Improving Refugee Access to Primary Care. Aust Fam Physician (2012) 41(3):147–9.

4.

UNHCR. UNHCR’s Refugee Data Finder (2023). Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/ (Accessed July 28, 2023).

5.

WHO. Mapping Health Systems’ Responsiveness to Refugee and Migrant Health Needs (2021). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

6.

Pysklywec M McLaughlin J Tew M Haines T . Doctors Within Borders: Meeting the Health Care Needs of Migrant Farm Workers in Canada. CMAJ (2011) 183(9):1039–43. 10.1503/cmaj.091404

7.

Gil-González D Carrasco-Portiño M Vives-Cases C Agudelo-Suárez AA Castejon Bolea R Ronda-Pérez E . Is Health a Right for All? An Umbrella Review of the Barriers to Health Care Access Faced by Migrants. Ethn Health (2015) 20(5):523–41. 10.1080/13557858.2014.946473

8.

Chuah FLH Tan ST Yeo J Legido-Quigley H . The Health Needs and Access Barriers Among Refugees and Asylum-Seekers in Malaysia: A Qualitative Study. Int J Equity Health (2018) 17(1):120–15. 10.1186/s12939-018-0833-x

9.

Hay G Castilla G . Object-Based Image Analysis: Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT). In:1st International Conference on Object-Based Image Analysis (OBIA 2006), Salzburg, Austria (2006).

10.

van Wijngaarden JD Scholten GR van Wijk KP . Strategic Analysis for Health Care Organizations: The Suitability of the SWOT-Analysis. Int J Health Plann Manage (2012) 27(1):34–49. 10.1002/hpm.1032

11.

Parliament Research Center. Electronic Database of Laws and Regulations of the Country (2023). Available from: https://rc.majlis.ir/fa/law (Accessed November 05, 2022).

12.

Legal Deputy of the President. Laws and Regulations Portal of Islamic Republic of Iran (2023). Available from: https://qavanin.ir/ (Accessed October 08, 2022).

13.

Ministry of health and medical education. National Database of Health Rules and Regulations (2003). Available from: http://healthcode.behdasht.gov.ir/approvals/ (Accessed October 10, 2022).

14.

Peters MD Godfrey CM Khalil H McInerney P Parker D Soares CB . Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc (2015) 13(3):141–6. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

15.

Smithman MA Descoteaux S Dionne E Richard L Breton M Khanassov V et al Typology of Organizational Innovation Components: Building Blocks to Improve Access to Primary Healthcare for Vulnerable Populations. Int J Equity Health (2020) 19(1):174. 10.1186/s12939-020-01263-8

16.

Levesque J-F Harris MF Russell G . Patient-Centred Access to Health Care: Conceptualising Access at the Interface of Health Systems and Populations. Int J Equity Health (2013) 12(1):18–9. 10.1186/1475-9276-12-18

17.

Cu A Meister S Lefebvre B Ridde V . Assessing Healthcare Access Using the Levesque’s Conceptual Framework–A Scoping Review. Int J Equity Health (2021) 20(1):116. 10.1186/s12939-021-01416-3

18.

Dzurova D Winkler P Drbohlav D . Immigrants' Access to Health Insurance: No Equality Without Awareness. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2014) 11(7):7144–53. 10.3390/ijerph110707144

19.

Ewen M Al Sakit M Saadeh R Laing R Vialle-Valentin C Seita A et al Comparative Assessment of Medicine Procurement Prices in the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). J Pharm Pol Pract (2014) 7(1):13. 10.1186/2052-3211-7-13

20.

Doocy S Lyles E Roberton T Akhu-Zaheya L Oweis A Burnham G . Prevalence and Care-Seeking for Chronic Diseases Among Syrian Refugees in Jordan. BMC Public Health (2015) 15:1097. 10.1186/s12889-015-2429-3

21.

Ay M Arcos Gonzalez P Castro Delgado R . The Perceived Barriers of Access to Health Care Among a Group of Non-Camp Syrian Refugees in Jordan. Int J Health Serv (2016) 46(3):566–89. 10.1177/0020731416636831

22.

Claassen K Jager P . Impact of the Introduction of the Electronic Health Insurance Card on the Use of Medical Services by Asylum Seekers in Germany. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2018) 15(5):856. 10.3390/ijerph15050856

23.

UN. Afghan Refugees and Undocumented Afghans (2022). Available from: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/infographic/afghan-refugees-and-undocumented-afghans#:∼:text=Another%20estimated%202.1%20million%20undocumented%20Afghans%20lived%20in,1%20January%20and%2028%20November%202021%20%28IOM%2C%202021%29 (Accessed November 20, 2022).

24.

Ghattas H Sassine AJ Seyfert K Nord M Sahyoun NR . Prevalence and Correlates of Food Insecurity Among Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon: Data From a Household Survey. PLoS One (2015) 10(6):e0130724. 10.1371/journal.pone.0130724

25.

Al-Rousan T Schwabkey Z Jirmanus L Nelson BD . Health Needs and Priorities of Syrian Refugees in Camps and Urban Settings in Jordan: Perspectives of Refugees and Health Care Providers. East Mediterr Health J (2018) 24(3):243–53. 10.26719/2018.24.3.243

26.

Mylius M Frewer A . Access to Healthcare for Undocumented Migrants With Communicable Diseases in Germany: A Quantitative Study. Eur J Public Health (2015) 25(4):582–6. 10.1093/eurpub/ckv023

27.

Zareipour M Jadgal MS Movahed EJJMM . Health Ambassadors Role in Self-Care During COVID-19 in Iran. J Mil Med (2020) 22(6):672–4.

28.

Doshmangir L Bazyar M Rashidian A Gordeev VS . Iran Health Insurance System in Transition: Equity Concerns and Steps to Achieve Universal Health Coverage. Int J Equity Health (2021) 20(1):37. 10.1186/s12939-020-01372-4

29.

Ekmekci PE . Syrian Refugees, Health and Migration Legislation in Turkey. J immigrant Minor Health (2017) 19(6):1434–41. 10.1007/s10903-016-0405-3

30.

Semeere AS Castelnuovo B Bbaale DS Kiragga AN Kigozi J Muganzi AM et al Innovative Demand Creation for Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision Targeting a High Impact Male Population: A Pilot Study Engaging Pregnant Women at Antenatal Clinics in Kampala, Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (2016) 72(4):S273–9. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001041

31.

O'Donnell CA Burns N Mair FS Dowrick C Clissmann C van den Muijsenbergh M et al Reducing the Health Care Burden for Marginalised Migrants: The Potential Role for Primary Care in Europe. Health Policy (2016) 120(5):495–508. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.03.012

32.

Takbiri A Takian A Rahimi Foroushani A Jaafaripooyan E . The Challenges of Providing Primary Health Care to Afghan Immigrants in Tehran: A Key Global Human Right Issue. Int J Hum Rights Healthc (2020) 13(3):259–73. 10.1108/ijhrh-06-2019-0042

33.

Chiarenza A Dauvrin M Chiesa V Baatout S Verrept H . Supporting Access to Healthcare for Refugees and Migrants in European Countries Under Particular Migratory Pressure. BMC Health Serv Res (2019) 19(1):513. 10.1186/s12913-019-4353-1

34.

Assi R Ozger-Ilhan S Ilhan MN . Health Needs and Access to Health Care: The Case of Syrian Refugees in Turkey. Public Health (2019) 172:146–52. 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.05.004

Summary

Keywords

migrant and refugee health, healthcare access, SWOT analysis, health systems, Iran

Citation

Bakhtiari A, Takian A, Olyaeemanesh A, Behzadifar M, Takbiri A, Sazgarnejad S and Kargar S (2023) Health System Response to Refugees’ and Migrants’ Health in Iran: A Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats Analysis and Policy Recommendations. Int J Public Health 68:1606268. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2023.1606268

Received

01 June 2023

Accepted

11 September 2023

Published

28 September 2023

Volume

68 - 2023

Edited by

Sonja Merten, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Switzerland

Reviewed by

Margaret Haworth-Brockman, University of Manitoba, Canada

Afona Chernet, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Switzerland

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Bakhtiari, Takian, Olyaeemanesh, Behzadifar, Takbiri, Sazgarnejad and Kargar.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Amirhossein Takian, takian@tums.ac.ir

This Original Article is part of the IJPH Special Issue “Migration Health Around the Globe—A Construction Site With Many Challenges”

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.